The bottle was on my mother’s dressing table, multiplied by three in the reflection of a trifold mirror. It fascinated me. The honey gold liquid, the blue crystal stopper in the shape of a fan. I was forbidden to touch it, but I knew what it contained: Guerlain Shalimar, the perfume my mother wore on special occasions that smelled like velvet and vanilla and places I had never seen. It signified mystery and grown-up glamour, and even though my age was still single digits, it stirred in me an inchoate desire to live the sort of worldly, textured life worthy of such a scent. I just needed to get out of Kansas first.

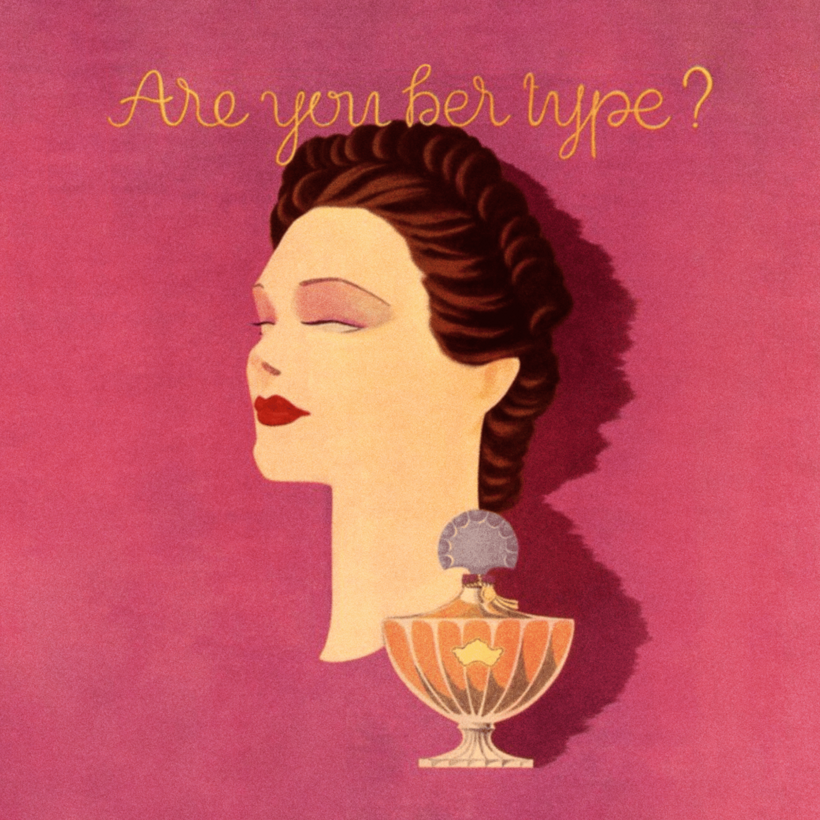

Shalimar’s story is steeped in stardust and myth. Jacques Guerlain conceived the fragrance as an ode to one of history’s most enduring love stories: that of 17th-century Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan, who memorialized his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal by building the shimmering white Taj Mahal and creating a royal pleasure garden in her honor called Shalimar.