Lady Harlech—Amanda, to most—will not be making a grand entrance at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute Gala on Monday. So what if the accompanying exhibition is devoted to the life and work of her longtime friend and associate Karl Lagerfeld?

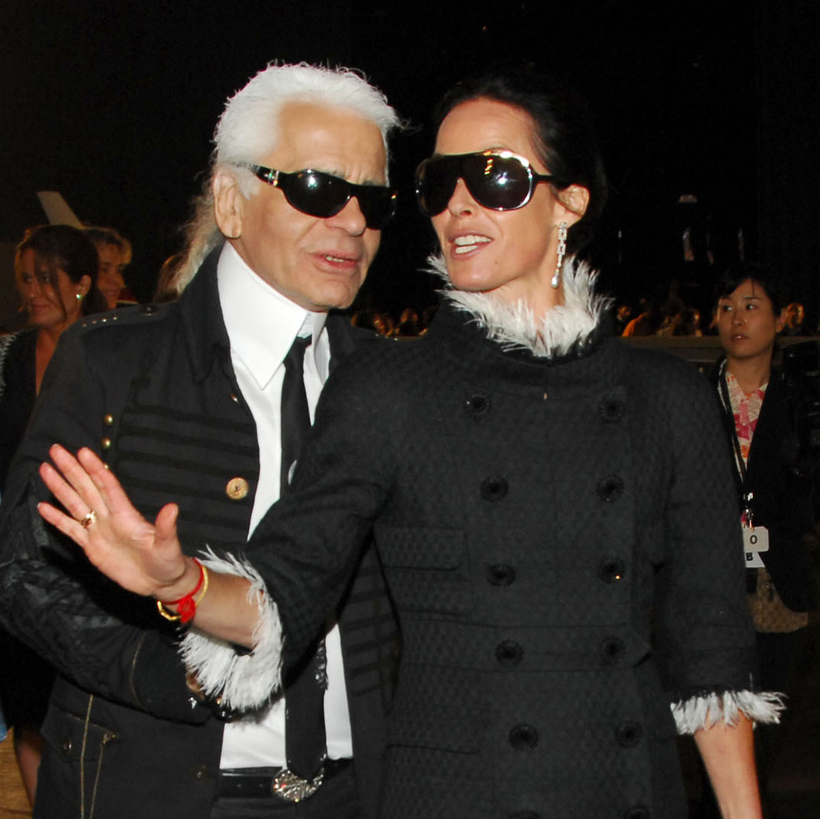

“It’s not me, not me,” she insists, sitting at a table at her Shropshire home, in a tone that brooks no argument. For 24 years, Harlech was a constant presence at his side, his muse, or an “extra pair of eyes,” as he often said, who worked alongside Lagerfeld at both Fendi and Chanel until his death, in 2019. (She is continuing in her work with Fendi, and she is also involved with a scholarship set up by Chanel and the British Fashion Council to nurture new talent.)

“He would be in total agreement,” she says, removing her ribbed round-neck jumper and lighting a cigarette. “He stopped going [to the Costume Institute Gala] because photographers were only interested in who he had on his arm.” But Harlech will not skip the affair entirely—she has decided to slip into the party through a back entrance.

It’s a shame on many counts. Not only is she a magnificent beauty, but she possesses the sort of dissonant and ineffable taste—a particularly British mix of punk and pomp, grounded in Lagerfeld’s Chanel aesthetic—that deserves to be celebrated, too.

“Every tatter is joy,” she says of the beaded dress from Chanel’s Fall 2008 haute couture collection that she plans to wear. “It looks like the seashore, water lapping in the moonlight with a bit of phosphorescence.”

She sighs, undoing her long raven tresses before immediately tying them back up again, and tugs at the neckline of her navy polo. It’s still early on Saturday morning, but she has already taken her horse for a ride and completed a cryotherapy session.

Harlech is the apotheosis of what aspirant foreigners imagine a British aristocrat to be. But she wasn’t born one—she married Francis Ormsby-Gore, the sixth Baron Harlech, in 1986—and doesn’t pretend that she was. The daughter of a solicitor, she was raised in London before attending Marlborough, Kate Middleton’s alma mater, in Wiltshire. From there, she earned a scholarship to read English at Somerville, Oxford.

Her time at Oxford sounds like a scene out of Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies. “There was this whole group of us,” she says. “We would go off to parties in sprawling country houses and castles in Scotland and drink magnums of champagne.” Among her classmates, she was very popular. “Sometimes there would be a boy lying outside my bedroom door to stop another one from coming in, but there was already one in my room,” she recalls. “That makes me sound awful, but I wasn’t.”

After graduation, she briefly contemplated writing a thesis on Henry James, but her great friend Sophie Hicks convinced her to indulge her love of fashion by working at Harpers & Queen magazine. It was her Damascene moment. “I had this seismic realization you could tell a story through a shoot, rather than sitting alone at your desk and writing it,” she says.

“Every tatter is joy.”

Toward the end of her four-year tenure there, on a shoot with Mario Testino and the model Susie Bick, she came across the collection that John Galliano had designed for his graduation from Central Saint Martins. “I couldn’t look at anything else,” she says. “It just felt like falling in love.”

Electrified by his rare and transgressive talent, she invited him to tea at her apartment in Chelsea. “He showed me his sketchbook—it was divine, extraordinarily febrile, his brushstrokes almost Egon Schiele–like,” she says. When Malcolm McLaren asked her to style the cover for his Fans album, she called on Galliano to design the clothing.

This was in 1986, when she was newly married and the mother of a young son, Jasset. (She and Ormsby-Gore had a daughter, Tallulah, two years later.) When Galliano offered to hire her, she agreed, and the two spent 10 years feeding ideas off each other before Galliano took a new job as creative director of Dior. Harlech was not brought along, but, in 1996, Karl Lagerfeld came calling.

Galliano never questioned her, but working at Chanel was very different. “Karl was already the flourishing emperor of fashion with a court around him—how could I fit in?” she says. “I often felt like the English exile.” It took Harlech a while to be accepted by her colleagues in the atelier. Whenever she suggested an alteration to a toile to one of the head couture seamstresses, la première would look, Harlech recalls, “like she’d bitten on a lemon.”

But Lagerfeld was a pleasure. “He could be incredibly kind,” she says. She recalls once arriving for a fitting in Venice with a swollen eyelid. “Karl said, ‘You look like Quasimodo, ’orrible, ’orrible, ’orrible!’ I think for him it would have been traumatizing to have a disfigurement like that.” The next day, he sent her the gold pillbox engraved with a landscape of Venice that still sits on her bedside table.

She describes their relationship as chiefly an artistic one, the two bonding over a shared love of literature, poetry, art, and music. Lagerfeld sent her endless crates of books (“I think he thought, ‘Poor girl, she needs something to do in the countryside,’” she says), promising to visit her in Shropshire, but ultimately he never made it. “I don’t think he wanted to be disappointed in someone he liked,” she says.

She has spent the past two years working with Andrew Bolton and Anna Wintour on the Met’s exhibition (including a re-creation of Lagerfeld’s desk), which was designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando. And now it’s time to pack, so she starts to prepare what she calls the “first cull” of her New York wardrobe.

“I had this little epiphany,” she says. “I’m not going to do uniform looks. I’m going to wear suede britches from the 30s with a tweed Norfolk jacket. I’ll be myself, but more comfortable.” Lagerfeld would approve.

Vassi Chamberlain is a London-based Writer at Large for AIR MAIL