The first film ever made was a home movie. It’s counter-intuitive and goes against every image we associate with the early years of cinema.

“Fred Ott’s Sneeze,” arguably the most emblematic short made at Thomas Edison’s studio in the late 19th century, is a blatant bit of marketing. Carefully choreographed and shot on the primitive soundstage known as “the Black Maria,” it was made primarily for publicity. The sneeze is a gag that showcases the novelty of film technology.

The two best-remembered films from the Lumière brothers’ first screenings, held in December of 1895 and January of 1896, are distinctly commercial as well. “Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory” is like an early corporate ad, showcasing the Cinématographe’s prowess but also the Lumières’ own brand (mentioned, as it is, in the title). “Arrival of a Train at la Ciotat,” apocryphal recollections of which have naïve viewers scrambling out of their seats to avoid being run over, has scale and showmanship written all over it.

The Lumières were bourgeois industrialists; Edison, though he fancied himself working-class his entire life, had his name on the letterhead of several international companies, and was running the world’s first for-profit research-and-development lab, heavily backed by bankers and financiers.

Film is commonly understood to have been a factory medium from its very inception, unlike writing, painting, music, or even photography. The equipment was expensive and its workings specialized, as were the production and distribution of the movies themselves. It’s called “show business” for a reason, emphasis on both halves of the blend.

We don’t think of people as having the tools to make little movies of their own families at home until the 1970s and the arrival of Kodak’s first Super 8 “amateur” cameras. Only, the first film ever made was precisely that: a little movie of the cameraperson’s own family, at home.

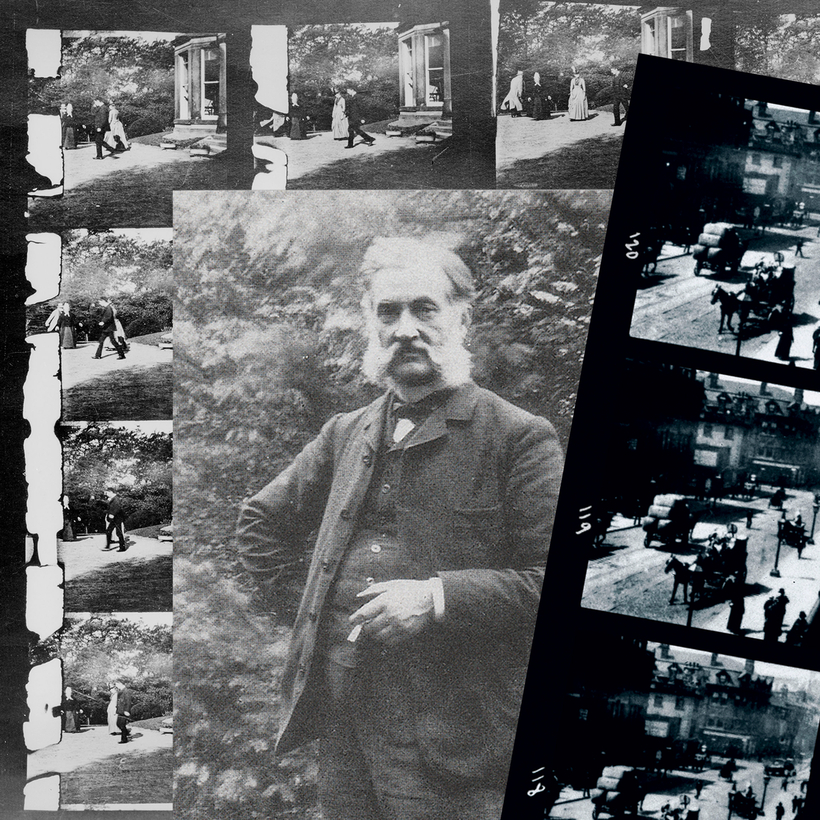

In October 1888, four and a half years before Edison’s first public demonstration of the Kinetoscope, and more than six years before the Lumières’ first films, a Frenchman by the name of Louis Le Prince shot a motion picture in his in-laws’ backyard, in Leeds, England.

Le Prince was a self-taught generalist. He had studied optics and chemistry, then gone on to work as a painter and a technical draftsman for an ironmonger in Leeds. Later, he ran a school of art with his wife. At various other times he had designed panorama entertainments and taught at a school for the deaf.

Photography was one of his passions. He’d had a vision of moving pictures when in his photo studio in the early 1880s, and had been working on a motion-picture camera ever since, first part-time, on his own, and then full-time, with a small crew of craftsmen in a rented workshop, sinking all his income into this obsession.

Le Prince’s home movie, known today as “Roundhay Garden Scene,” still exists. As do Le Prince’s camera and projector, held in the collection of England’s National Science and Media Museum. For these Le Prince was granted patents in several countries, a year before Thomas Edison even began his own motion-picture experiments.

The underlying principles of Le Prince’s film camera are modern, and English technicians, using an exact replica of the machine, used it successfully with modern film in 2015. Le Prince’s notebooks contain sketches for what he called a “people’s theatre” for moving images, recognizable immediately as a rudimentary cinema.

History has forgotten Le Prince in part because he disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1890, and in part because he never held a commercial screening of his work before he vanished. His family wrote that he had considered bringing his prototypes to Thomas Edison, in an attempt to pitch the famous inventor into a collaboration, but Le Prince didn’t follow through, and he and Edison never met. When Edison announced his Kinetoscope, just months after Le Prince went missing, the family became convinced Edison had been involved in his disappearance.

By law, we identify the first person to have invented a technology by the date on their patent, and by this standard Le Prince was the first. In practice, though, capitalism has got us used to thinking of income as the only reliable metric. An innovation exists—in the sense that it is and that it works—only once someone is able to sell it.

Le Prince’s “Roundhay Garden Scene” never grossed a penny. But it’s tantalizing to think of how differently we’d conceive of the medium if it were better known that it wasn’t born in well-funded studios but in the hands of one man, making a little recording of his loved ones at home.

Evidence suggests Le Prince thought of film as, in part, a more modern version of the family photo album. One day, he figured, everyone might have a collection of films at home, as they had a picture album and a magic-lantern slideshow. It was an incredibly prescient instinct, and “Roundhay Garden Scene”—a few seconds of people at home, self-consciously acting up to the camera—has more in common with the videos that each of us shoot on our phones today than it does with anything Edison or the Lumières made a few years later.

Paul Fischer’s The Man Who Invented Motion Pictures: A True Tale of Obsession, Murder, and the Movies will be published on April 19 by Simon & Schuster