In the end, a human being can’t actually be a book, no matter how hard they try; but Roberto Calasso came close.

It’s not just that Calasso, who died last week in Milan at the age of 80, was a renowned writer—the author of the international best-seller The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, an elegant retelling of most of Greek mythology, and other books on history and religion. He was also one of Italy’s leading publishers. As editorial director of the independent house Adelphi Edizioni since 1971, Calasso introduced Italian readers to Jorge Luis Borges, J. R. R. Tolkien, and Vladimir Nabokov, among many others.

What’s more, he had one of the world’s great book collections, including first editions of Spinoza and Kafka. And he actually read them: in addition to his native Italian, Calasso was fluent in French, English, Spanish, and German, and read Greek and Latin. He taught himself Sanskrit while working on Ka, his book about Indian mythology.

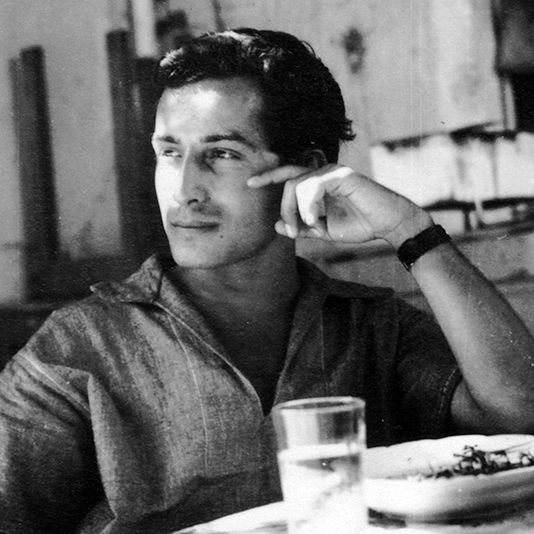

It’s tempting to say that Calasso’s death marks the end of an era of high literacy, when people aspired to become books rather than memes. But the truth is that he was a countercultural figure even in his day. Born in 1941, he was part of a global generation shaped far more by Hollywood and rock ’n’ roll than by literature. As a teenager in Rome, Calasso said in a 2012 Paris Review interview, he went to the movies once or twice a day. Marlon Brando was his favorite film star: “I saw On the Waterfront at least seven times,” he said.

At home, however, Calasso was exposed to a different, older culture. His father was a professor of legal history and his mother had a Ph.D. in ancient Greek literature. He grew up surrounded by exotic tomes from the 18th century and even earlier: “Rather impressive folios, many of them, and mostly in Latin. Just to see them around, with their obscure titles and authors, was far more useful to me than reading so many other books later on,” Calasso recalled.

He never lost the sense that important knowledge is found in recondite old books, rather than cutting-edge theories or scientific experiments. Any new book is indebted to its predecessors to some degree, but Calasso took this to an extreme: his books are made of books. His last work—on the Bible, due to be published in English in November—is actually titled The Book of All Books.

It’s tempting to say that Calasso’s death marks the end of an era of high literacy, when people aspired to become books rather than memes. But the truth is that he was a countercultural figure even in his day.

Calasso’s books are precious in both the good and bad senses: rare and valuable, and a little over-refined. His method is to pick a big subject—Greek or Hindu myth, the French Revolution (in The Ruin of Kasch), 19th-century Paris (in La Folie Baudelaire)—and then roam among the countless books written about it, alighting on whatever seizes his attention: images, stories, characters, quotations. He weaves these together with his own insights and ruminations, creating a text that’s not a narrative or an argument so much as a pattern or an atmosphere. “I have never written a book … from beginning to end,” Calasso said. “It is always a mosaic, if you will, in which I write page 80, 30, 315 in any given order.”

His footnotes are an education in themselves. The first chapter of The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony, for instance, draws on the canonical classical sources you’d expect—The Iliad, The Aeneid, Ovid’s Metamorphoses—but also on arcana such as Nonnus’s Dionysiaca, a pastiche epic from the fifth century A.D. whose only claim to fame is that it is the longest-surviving Greek poem, at 20,426 lines.

Yet The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony is Calasso’s most accessible book by some distance. It can be read simply as a collection of good stories: Theseus slaying the Minotaur; Athena emerging from the brow of her father, Zeus; Demeter rescuing her daughter Persephone from the underworld. Unlike some popular retellings, Calasso’s doesn’t downplay the sex and violence that pulse through Greek myths. Hera, for instance, often features as a jealous wife, policing the wandering eye of her husband, Zeus. But Calasso reminds us that she was herself the primal goddess of sex: “In her most majestic shrine, the Heraion in Argos, the worshiper could see, placed on a votive table, an image of Hera’s mouth closed amorously around Zeus’s erect phallus. No other goddess, not even Aphrodite, had allowed an image like that in her shrine.”

Even as he retells myths, however, Calasso is also telling us something about the nature of myth. Modern stories, the kind found in novels, are told once and for all. The story of Anna Karenina is the story Tolstoy wrote; if you said that Anna didn’t actually die on the railroad tracks, but escaped and lived happily ever after with her lover, Vronsky, people would think you hadn’t read the book (or maybe hadn’t finished it).

Mythic stories, by contrast, exist in many versions that are all equally true, even when they’re incompatible. Calasso insists on this multiplicity. “But how did it all begin?” he asks, introducing the story of Europa’s abduction by Zeus, and then repeats the formula three more times, giving a different version each time. “Stories never live alone: they are the branches of a family that we have to trace back, and forward,” he writes.

Unlike some popular retellings, Calasso’s doesn’t downplay the sex and violence that pulse through Greek myths.

In the ancient world, which Calasso writes about in The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony and Ka, humanity was able to believe in this kind of story. In the modern world, which is the subject of The Ruin of Kasch, La Folie Baudelaire, and other books, our relationship to myths is more complicated. Officially, we no longer believe in the gods. We think that our lives are determined by the sum of our choices, not by the recurrence of archetypes.

But the central insight of Calasso’s work is that we can’t escape myth so easily. Calasso isn’t religious, exactly—he doesn’t write as an adherent of any particular faith—but he strongly believes that humanity requires a connection to the divine. As he writes in The Unnamable Present, “without the thrill of the numinous, secular society refuses to exist.”

Above all, we have a primal need to sacrifice—to destroy something or someone in order to appease the gods. Ancient religion met that need by slaughtering animals and burning them on the altar. Today we scoff at animal sacrifice, but we periodically engage in the mass slaughter of human beings in the name of an idea. As Calasso writes in The Ruin of Kasch, “The world is held in this silent grip between a sacrifice that is performed unnamed and a sacrifice that is continually named but is fictitious.”

Calasso has a horror of this kind of ideological sacrifice, whether it takes the form of the French Revolution, Communism, or Nazism. Maybe, he suggests, modern humanity would be less prone to violent revolution if we could once again acknowledge the sacred dimension of existence. That was Calasso’s ultimate ambition for a human life, which he achieved as well as anyone can in the 21st century: “for each to die in their own way, to draw a final arabesque before the return to that mute stillness that ignores meaning.”

Adam Kirsch is the author of The Blessing and the Curse: The Jewish People and Their Books in the Twentieth Century and an editor for The Wall Street Journal’s weekend Review section