The boar is off the floor. Fighting for vengeance and survival, Logan Roy has turned full beast. One can’t help thinking that the monstrous media magnate at the cancerous center of HBO’s extraordinary hit series Succession has it easier than the show’s creator, Jesse Armstrong.

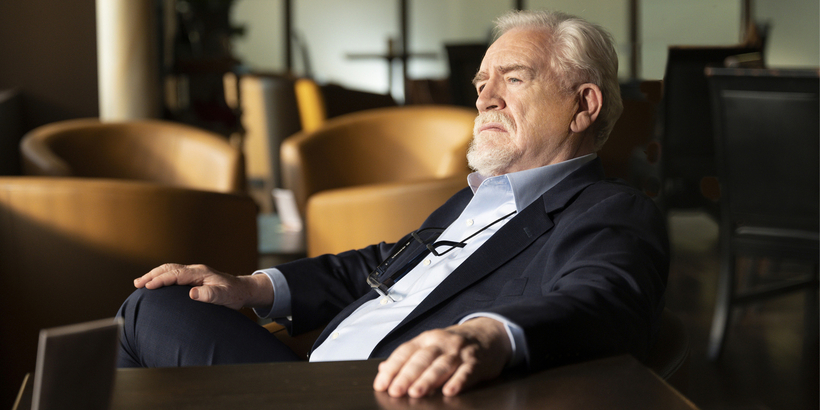

Logan, played by Armstrong’s fellow Brit Brian Cox, needs only to destroy Kendall, the lightweight, scapegoated son who at the end of last season convened a press conference to denounce his father as a “malignant presence, bully and a liar”. Armstrong has surely the harder task of maintaining the stratospheric standards of a comedy drama whose quality is now being compared to The Sopranos.

Armstrong need not worry. The third season’s debut episode on Monday won its biggest audience for Sky Atlantic and Now, opening with more than four times as many viewers as the previous season’s launch. Critics have all but unanimously awarded five-star reviews.

“It feels like it went OK, so that’s nice,” says Armstrong, a modest man speaking from his London home where he writes most of Succession. His show, he points out, hasn’t Game of Thrones’ audiences, but the ever louder buzz as the new run approached could not be ignored. “People seemed genuinely interested to find out what happened next.”

In Monday’s episode Kendall summarized the Roy family dynamic succinctly: “My dad’s the devil.” With Logan’s henchmen reciting a catalogue of his past sins, including knowledge of deaths and sexual assaults aboard Waystar Royco’s cruise line, it is a wonder we viewers have so much time for him. William Blake accused Milton of being “of the devil’s party without knowing it” in Paradise Lost. I wonder whether Armstrong will own up to a similar thought crime.

“That’s territory that you have to have in mind,” he responds. “If you’re writing somewhat monstrous figures, people will relate to them, but relating is OK, and so is seeing flashes of their point of view. I also think — and this isn’t a cop-out at all; this is the hard truth — it’s down to the audience.

Armstrong has surely the harder task of maintaining the stratospheric standards of a comedy drama whose quality is now being compared to The Sopranos.

“My moral responsibility is creating a show that bears relationship to the world and presenting everyone the evidence. You’re responsible for your own judgments. If you find something appealing in somebody awful, then that’s on you.”

Jeremy Strong, who plays Kendall, has admitted that on one occasion he burst into tears when Cox as Logan unexpectedly shouted at him. Is Armstrong ever scared by Cox on set? “No,” he says. “I feel the thrill of catching lightning in the bottle.”

Monday’s opener was more Kendall’s episode than Logan’s. Desperate for affirmation, nursing a wobbly Messiah complex, clueless how to prevent being destroyed by his own bombshell, Kendall remained Succession’s most vulnerable entity. I wonder if Armstrong worries about Strong, a practitioner of the Method school of ultra-intense acting, as he writes Kendall into an emotional wringer. “Honestly? I try not to. I know Jeremy. I’m very fond of him. There’s a whole range of feelings about the actors who I’ve become closer to and know and I’m very fond of, and if I thought too much about what the plot lines were going to require or not require of individuals both at the center and the periphery, then that would be a disaster.

“It would be inhuman at certain points not to think those thoughts, but during the creative process it would be a disaster and if I thought, ‘Oh my God, if we have Jeremy’s character involved in a crash and he’s going to really dive into that icy water, it’s going to be tough.’

“It would not be good for him, or to think too much about that. So I try not to, and so far I think I’ve succeeded. You get carried away by the excitement of the reality of the situations and it has to be the way. I’m afraid you need that slight chip of ice in your heart.”

Armstrong has more sympathy for viewers who find the embarrassments and humiliations inflicted on Succession’s characters excruciating. “I used to find Fawlty Towers and The Office and Alan Partridge, which are probably three of my favorite shows, almost unwatchable because of the level of anxiety they induced. I found those characters, their plights, very believable. I think there’s a number of reasons people find the show resistible or don’t watch it, but that’s the one most easy for me to sympathize with.”

I suppose it takes courage to push so far? “It doesn’t feel that courageous. It feels interesting. That’s our primary intellectual approach to the characters.”

“My moral responsibility is creating a show that bears relationship to the world and presenting everyone the evidence.”

Armstrong may forgive viewers’ squeamishness but won’t spoon-feed us answers. He will neither confirm nor deny that he had Lady Macbeth in mind when the regicidal Kendall stared at his (metaphorically) bloodied hands on Monday.

He cannot conceal that the surname “Roy” is derived from “roi”, or “king”, but disputes “Logan” is a corruption of “Lear” — he did not see Cox’s Lear in the 1990s and only read his book The Lear Diaries after he was cast.

A greater influence was Stalin, who held parties that were “ostensibly jovial but also expressions of power”. They inspired last season’s boar-on-the floor game, in which Logan’s acolytes crawled about a country house while being hit by sausages.

There are eight more episodes to relish this season, but how many further seasons can we hope for? “Putting a number on it feels like a weird thing to do. What I’ve tended to say is, ‘I don’t think it should go on for ever.’ There’s a certain promise in the title and I think it could become uninteresting to me and my fellow writers, and the world, if we carried it on beyond a certain point, but I don’t want to say exactly when that is now.”

Could it continue without Logan? “Theoretically I think it could do,” Armstrong says without much enthusiasm. The fact is, in Succession’s initial conception Logan was due to die if not in the pilot episode then at the end of season one. This, he says, is an example of a writers’ room’s creative destruction. “I do have a plan, but that plan may not be executed.”

Like a Waystar meeting? “Exactly. No plan survives contact with the enemy, as they say in warfare.”

It has become orthodoxy that Succession got off to a slow start in 2018. My only objection was to an early scene that seemed too crude, the one in which Kendall’s younger brother Roman ejaculated over the Waystar boardroom window.

Armstrong says to speak in public about what Succession might have done differently feels too “icky to the people involved”. He stands by this scene, however. “I think it’s him taking ownership of his space. I mean it’s very vivid. I can see maybe too vivid … but I don’t mind that.”

I read him another criticism, this from the playwright David Hare, who told The Times that Succession “doesn’t have any politics” but is a “restoration comedy”. Armstrong laughs too hard for me to complete the quote: “That’s his reading, so fair do’s to him.”

But does the show have a view about media power and ownership? “Very much so. I think if you were to invest this much time and effort into something which didn’t, it would be a very odd endeavor.

“I think the media environment in the US is a big problem, and in terms of the tenor of public debate. I’m wary of starting to become a think tank when talking about the drama, but yes, I do think the show is engaged with those questions. If you watch it carefully you’d think it does too.”

He has always maintained that Succession is not directly based on any one of the great media dynasties — the Murdochs (Rupert Murdoch is the proprietor of this paper), the Sulzbergers (owners of The New York Times) or the Redstones (who ran ViacomCBS) — but is it his intention to wound them? “Like in a personal, roman-à-clef way? No, no, no. No.”

Armstrong, who co-wrote Peep Show, Fresh Meat and three seasons of The Thick of It, has had a terrific career in Britain, but his first American success has brought a new level of acclaim. He was brought up in Oswestry, Shropshire, where he attended the local comprehensive.

His father, David, was a teacher who became a crime novelist. His mother opened a small shop. Is there a danger that, aged 50, their son may become one of the rich and famous that Succession satirizes? He sounds troubled by the thought.

“I mean, I fly to America a lot to do the show and it’s a lifestyle that I wasn’t used to. It’s a big show for HBO and the budget allows us to do big things. I was there on that yacht [in the season two finale]. In a sense, there’s a way in which you are part of it and, yes, I’ve got a different relationship to it than other people … I don’t know. That’s a potentially uncomfortable area there we’re talking about.”

Armstrong may be HBO royalty, but he is in no danger of becoming a Roy. I even prise a state secret from him. Succession has new opening titles, which means fresh glimpses of Waystar Royco’s agenda-led “journalism”. A ticker display, for example, reads: “Hollywood boss sneers: ‘If the poor are so poor why aren’t they … ’ “. The titles then cut to another shot. How did that headline end? ” ‘Thinner’,” Armstrong replies.

With Succession the devil is not only in Logan Roy. It is in the detail.

Andrew Billen is a staff feature writer for The Times of London