In the dark of night, a man named Armand appeared at my front door in downtown Los Angeles to fetch the precious goods: eight floppy diskettes, bound by a rubber band, exact contents unknown. I’d bought my own USB-enabled reader and discovered it wouldn’t translate these antiquated bits into readable ones. I had no idea what was on them, but I was dying to find out.

For a modest fee, this Armand fellow was happy to help. He even happened to be dropping off his daughter at a burlesque show (?) near my place and could save me the trip to his—I’d trust the disks to this total stranger who offered data transfer services, but no way was I trusting these to the mail.

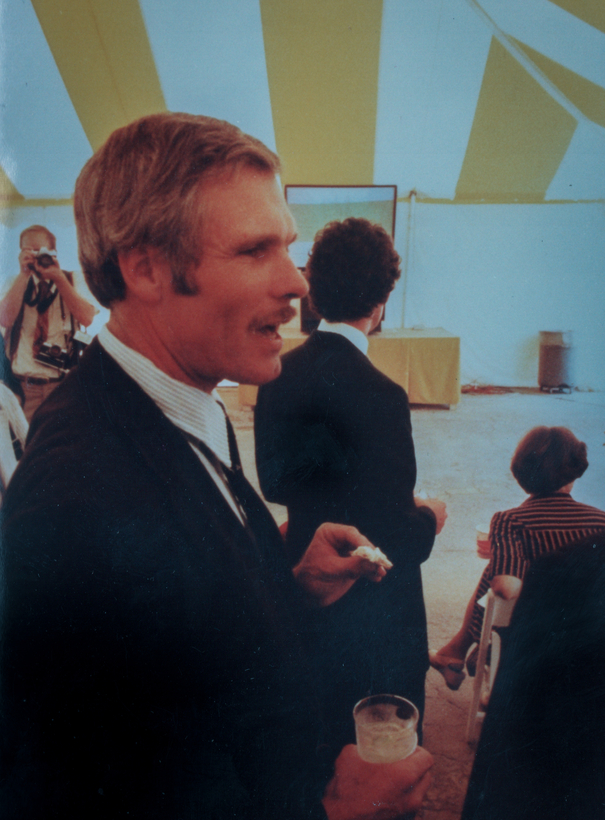

Sleuthing out possible Rosetta stones, quirky gems, and garrulous witnesses is the thrill of writing biography. This quest for detail is an allowable distraction that serves another important purpose: It takes you away from the otherwise torturous slog of hours at a keyboard. (Media mogul Ted Turner once declared he was “cable before cable was cool.” Well, writers were masters of self-isolation before it was a public health necessity.)

A Perfect Sleuth

In this case, I happened to be writing about Turner’s crowning achievement, the first all-news channel, CNN, which turned 40 on June 1. And while reading the 2001 memoir of the network’s chief architect and original president, Reese Schonfeld, as well as various associated articles, I discovered the first draft had been co-written by a formidable New York writer named Chris Chase. Back then, Chase had interviewed innumerable originals. Boy, did I want to get my hands on that book that never got published.

I had an odd connection: I happened to have started my career at age 17 at CNN’s New York bureau, then located in the base of the World Trade Center, as Chris Chase’s intern. In 1981, when only a fraction of the universe was wired for cable and no on knew if CNN would make it to year two, it was literally possible for a kid like me, from Flatbush, to dial up “Chicken Noodle News” and be welcomed in the door. Heck, I knew how to answer a phone—I was useful! Chase was the nascent network’s media commentator, but, most impressive to me, an aspiring young journalist, was her regular byline in the gilded New York Times. My family was more of a New York Post household, but I snuck a copy of the old Grey Lady every chance I got.

Sadly, Chase was gone now. So, I began the quest for her papers—figuring, hoping, that a woman who’d written books with Betty Ford and Rosalind Russell wouldn’t have just tossed her archives into a dumpster. After rooting around a bit, I discovered the correct people, who said I may have the materials if A. Reese Schonfeld gave permission and B. if they could find them. Well, Schonfeld (who didn’t have them himself) did give his permission, and, as it turned out, they couldn’t.

Boy, did I want to get my hands on that book that never got published.

Every stone overturned in search of material—every person you talk to, even if she just leads you to another—is a crucial building block in biography. I continued down my ever-growing wish-list. Various CNN originals generously dug around in their basements and attics and unearthed memos, early training manuals for “CNN College,” and never-before-published photographs of June 1, 1980, the network’s very first day.

A self-published book by an early Turner employee inspired me to call an archive in Georgia in which I located a rare copy of “Super Ted,” a 20-minute video written and acted by his colleagues at WTCG, the UHF station that spawned his empire, in which he’s mightily lampooned as a super hero. Then there was the discovery that made me glad to still be living in Los Angeles: The father-son writing team of Gerald Jay Goldberg and Robert Goldberg had left their materials to UCLA’s Special Collections, including hours of musty cassettes containing interviews for their 1995 book, Citizen Turner: The Wild Rise of an American Tycoon. For days in that glorious reading room I would sit, surrounded by fellow researchers examining scrolls with magnifying glasses, wearing clunky can headphones and listening to conversations one Goldberg or the other had long ago with a variety of key players—some now dead, many of whose memories by now had faded.

Searches unearthed training manuals for “CNN College” and never-before-published photographs of the network’s first day.

The top item on my list eluded me: a tape of Fidel Castro in 1982 offering a testimonial of the then two-year old CNN. That Ted Turner visited Cuba at Castro’s invitation would be a pivotal part of my story. Best I could tell, only three people on earth were in possession of the video. One searched and couldn’t find it. Another never responded to my queries. The third was Turner himself, who has a rare form of dementia.

His staff generously offered a spreadsheet of materials in his personal collection that might include the tape. I searched the document, and there it was. They were happy to loan me a copy. Eureka!

Its arrival surpassed my greatest research achievement from my last book: locating the divorce papers, never completed, of Joan Kroc when she planned to leave Ray. But soon came another triumph, word that some interesting-looking materials had turned up in Chase’s papers and they just might be what I was looking for. Thirty-six hours after I handed Armand those diskettes, the files appeared on my desktop. I never got to thank Chase for launching me into the world so long ago, but now, nearly 40 years later, I tilted my head to the heavens in appreciation. Sorry, Marie Kondo. Archives matter. They enrich the research of gals from Flatbush, like me.

Lisa Napoli’s Up All Night: Ted Turner, CNN, and the Birth of 24-Hour News is out now from Abrams