When Béla Bartók’s Freudian nightmare Bluebeard’s Castle premiered at the New York City Opera in 1952, Time magazine foresaw a rosy future for the show in the company’s repertory. After all, the unnamed critic reasoned, “psychoanalysis is popular in New York.”

Time—historical time, that is, not the publication—told otherwise. In truth, the Hungarian master’s lone foray into the lyric medium has never escaped the category Hamlet calls “caviar to the general,” which is to say, wasted on the hoi polloi. Since its Budapest premiere in 1918, the deliberately paced, splendiferously orchestrated hourlong one-act tango for two has survived thanks to adventurous maestros who have kept up a trickle—never a stream—of festival-caliber concert performances and full-dress stagings. The Metropolitan Opera production that was filmed live on February 11, 1989, starring Samuel Ramey and Jessye Norman in peak form under the baton of James Levine, ranks with the most thrilling of the lot.

The narrative is simple to a fault. At curtain rise, the morose title character arrives at the threshold of his citadel with his starry-eyed fourth bride Judith in tow. Crossing the threshold, she finds a shadowy, ominous hall with seven locked doors. Like an analyst patiently chipping away at a patient’s resistance, she is determined to dispel the darkness with light. One by one, she obtains seven keys, discovering first a torture chamber, then an armory, a treasure house, a secret garden, an unbounded landscape, a lake of tears, and finally Bluebeard’s first three wives, mute but living, regally bejeweled.

For vocal glamour elevated by personal charisma, the Met’s newlyweds score a perfect 10. Somewhat unexpectedly, given the custom of international houses, they sing the text (by Béla Balázs) not in the original Hungarian but in Chester Kallman’s lucid, suitably formal English translation. For long stretches, no recourse to subtitles is required; viewers can instead zero in on the faces, often shown in eloquent close-up.

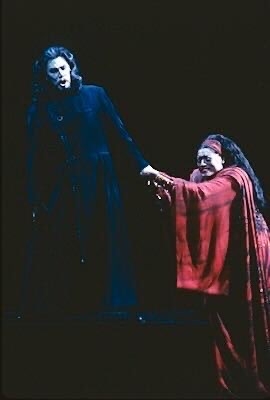

Rocking locks worthy of the unshorn Samson, Ramey’s Bluebeard brandishes his laser-focused, pitch-dark bass with Mosaic authority, yet at the top of the show he quivers with subliminal apprehension. Nerves on the artist’s part? Jitters on the part of the character? Who can tell? And how much daylight might there be between Norman’s generous diva persona, the flooding radiance of her soprano, and Judith’s naïve rapture? Why even try to parse? As revelation follows revelation, Bluebeard embraces his guilt-tinged machismo, even as Judith sinks into outright horror and hushed dread. Gaze where she may, she sees blood.

Ramey and Norman enact their ritual with spellbinding concentration, borne aloft on Bartók’s maximalist magic carpet of symphonic sound, all the richer for the exotic impact of mallets on metal and the pipe organ’s incense for the ears. The trailblazing video director Brian Large prioritizes people over theatrical packaging, so Göran Järvefelt’s monolithic, ungimmicky production registers only peripherally. Still, it does its work.

Bluebeard’s Castle is available for streaming on Met Opera on Demand

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii