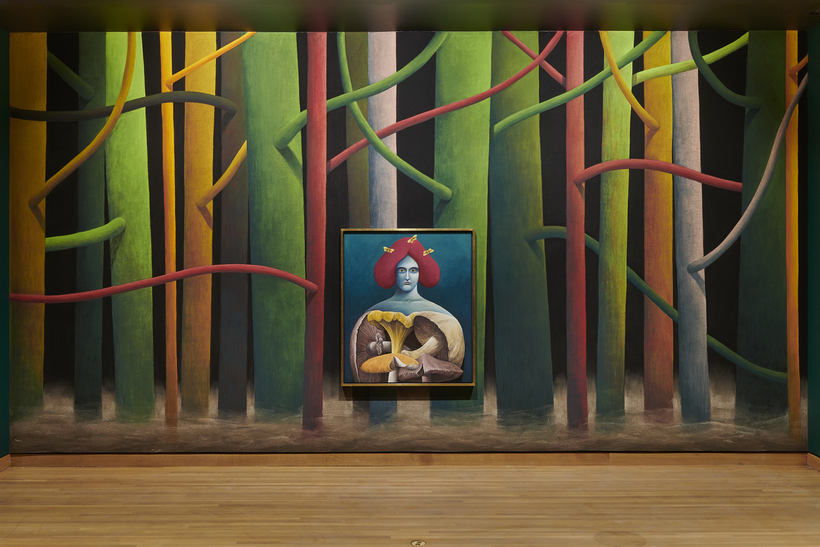

The Swiss artist Nicolas Party paints murals and landscapes that may remind viewers of computer-generated images in a virtual space. In his characteristic way, Party strips his subjects of detail, rendering their features and elements curvaceously alien. His make-believe color palette is vivid and his brushwork sharp. While Party’s faces are round and wide-eyed, his landscapes feel calculated and geometrical. Sometimes he revisits masterpieces from the Old Masters, and other times he brings the Fauves or Milton Avery to mind.

Charismatic and genial, Party is now 41 and has traded his childhood home in the Alps for a studio in New York. His latest solo exhibition, “L’heure mauve,” is now on through October at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and includes watercolors, pastels, and sculptures. AIR MAIL recently caught up with the rising art star.

Elena Clavarino: When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

Nicolas Party: When do people in general know? All children paint, and I guess the difference is some just keep going. Everybody starts as an artist. Everybody’s creative when they’re young. When it gets to your teenage years, people start to lose interest. Or maybe it’s society that tells us that it’s not important to spend too much time doing this. So I think the difference is I just kept doing it. I still do my childish little things.

E.C.: Your work reminds me of fairy tales. Are you always trying to return to the child in you?

N.P.: I definitely want to create a world that is inviting and a bit enchanted, so I’m not against the fairy tale narrative. And maybe there’s a connection. When these tales were written, they were a mix of something quite dreamy and quite aesthetic, but also something quite grim and horrible. It was a lot about making children scared so they didn’t do anything wrong outside their village or town. It was a way of controlling them. The power of the symbol in all those old stories is, I think, very interesting.

E.C.: You grew up in Switzerland, around mountains and lakes, and then moved to New York. Do you miss outdoor environments when you’re creating? Especially when you’re working on landscapes?

N.P.: We have a house in the countryside, so I do go every other weekend and it’s very remote. It’s in an area called the Catskills, and I love going there, biking there, and being more in touch with what we describe as nature. But I don’t paint trees from the outdoors, they’re more inside my head. I don’t need to be surrounded by nature to paint nature.

E.C.: What inspired you to use pastel? I know it’s not a very popular medium in contemporary art.

N.P.: I fell in love with it 10 years ago. It’s very visceral, and you work with your hands. It’s very powdery, so it feels like makeup. It’s intuitive and you can work very fast. In acrylic, you have a lot of plastic, or oil, so it makes painting very shiny. With pastel, it’s very matte, so the light is really taken into the painting. Also, I’m interested in the history of the medium, and how it was gendered. It was really categorized as something soft and easy, and attributed to women in the late 18th century, and that’s one of the reasons that it’s still kind of dismissed by a very male-oriented artistry.

E.C.: Your color sense is reminiscent of Milton Avery’s.

N.P.: Oh, I really appreciate that. I actually have two Averys here and one at home. I buy his work and I love it. I discovered Avery when I came to the U.S. because he’s not very well known in Europe. His way of using color is extremely unique. There’s not really a lot of rendering; it’s quite flat. And how he’s combining color has a really tremendous effect on how you perceive subjects that are quite often simple. It can be a few gulls on a beach, or a portrait of someone sitting down. With color, he can create a very strong psychological atmosphere.

E.C.: Who else do you look to in your work?

N.P.: Speaking of pastel, another person is Rosalba Carriera. She’s this incredible artist from Venice that made pastel popular in the early 18th century. She’s the queen of pastel, and if you do pastel, then you want to own her work. I have two Rosalba Carriera works that I bought two or three years ago. She was doing mostly portraits, but her portraits are very, very voluptuous and sensual. She really captures something in the faces of the models that is incredible.

E.C.: What led you to create these kind of mutant figures that are somewhat ambiguous? Are they men? Are they women?

N.P.: The idea was to explore how we define gender. The face is the thing that we look at the most in people, and there’s very, very little difference, except that men obviously have a beard that women rarely have. Culture has been creating two faces for men and women, but that’s more like an idea. If we all had shaved heads and no beards, we would have physically the same face. I was intrigued by the Greeks’ ideal face. Greek faces are nondescript. It was the Romans who started to differentiate between men and women.

E.C.: So you’re painting or sculpting a universal face?

N.P.: Yes. And questioning that very direct question, “Oh, is it a man or woman?” Does it matter?

E.C.: You create immersive environments with your murals and sculptures. Do you think this should be the process by which we view art in general, or is big and bold your style?

N.P.: Everything that we see is in a chosen context. I sometimes decide to change that context. Painting a wall white is a decision—an aesthetic and cultural decision. It means something. White is a color with a history. Sometimes I feel like taking a bit more control and not being a contributor to the so-called white cube.

E.C.: Can you talk about the show in Montreal?

N.P.: Stéphane Aquin, the director, invited me to choose works from the collection and mix them up with my murals. We created a narrative around it. The narrative is about our relationship to nature and culture, shown through different examples in art history. Because, of course, our perception of what we describe as nature has been changing, in terms of the conflict that we have with it. Nowadays, it’s very present in our consciousness.

“L’heure mauve” is on at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts through October 16

Elena Clavarino is an Associate Editor for AIR MAIL