Wedding Ring. Sunburst. Pinecone. Lone Star. Honeycomb. Patchwork quilting is a craft based on patterns, a form of folk art that sees scraps of fabric worked into intricately-designed bed coverings—a meeting of thrift and vision. A traditional mother-daughter venture, this enduring version of “loving hands at home” has produced works of art through the centuries, as we see in our museums. The image of the honeycomb, with its suggestion of quilting bees and busy hands working in concert, captures the communal hive of many patchwork quilts. And then there are the lone stars, women like Harriet Powers, who was born a slave in Georgia, was freed at the end of the Civil War, and began making quilts while raising nine children. Two of these quilts survive and they are masterpieces.

Powers lived from 1837 to 1910 and was a contemporary of Harriet Tubman. In her hands the quilt became a site of poetic transport, possessing the negative space, the homespun surrealism, of verse by Emily Dickinson (another American contemporary). The Smithsonian Museum holds Powers’s Bible Quilt (1886); her Pictorial Quilt (1898) is at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. In both, the storytelling that Powers pulls from piecework and appliqué—captured in square chambers like the cinema to come—draws upon African and African-American influences. Her sense of silhouette rivals any cutout by Matisse.

We know that the textile arts have been deemed secondary for a long time. This is partly because fabric and fibers are so perishable, and partly because they are mediums in which women’s fingers do the work. I wonder what Powers would think if she saw the current generation of Black women—men, too, such as Christopher Myers—who have turned the piecework and appliqué of quilting into one of today’s most exciting art forms.

Harriet Powers’s sense of silhouette rivals any cutout by Matisse.

Looking at the cloth collages of Billie Zangewa, whose exhibition “Wings of Change” is on through November 7 at Lehmann Maupin in New York, it’s hard to think of piecework as humble, so elegant and ethereal are these hand-stitched images of what Zangewa calls “daily feminism”—scenes, she says, that “focus on the things that women do at home that aren’t seen or appreciated or acknowledged.” Also through November 7, in a wonderful online exhibition at Fort Gansevoort, is “Dawn Williams Boyd: Cloth Paintings.” Boyd is based in Atlanta, Georgia, and has been “painting” with cloth for four decades. She works on a large scale, her figures life-sized, though you can’t see that on a computer screen. What you do see is the way she lays in social commentary—“Money is made of Cotton,” “Cowards always come in the night.” It’s both stunning and moving.

At the Bronx Museum, 50 quilt-based works by the interdisciplinary artist Sanford Biggers are on view through January 24, 2021. Biggers began working with quilts when he discovered—while fulfilling a 2009 commission for the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, a stop on the Underground Railroad—that quilts had been hung on fences and in yards as navigational signals for escaping slaves. The quilts were codes. Hence the name of this exhibition, “Codeswitch,” in which Biggers has layered his own meanings and codes upon 19th-century quilts, through painting, collage, cutting, and reconstruction.

I wonder what Powers would think if she saw the current generation of Black women—men, too—who have turned quilting into one of today’s most exciting art forms.

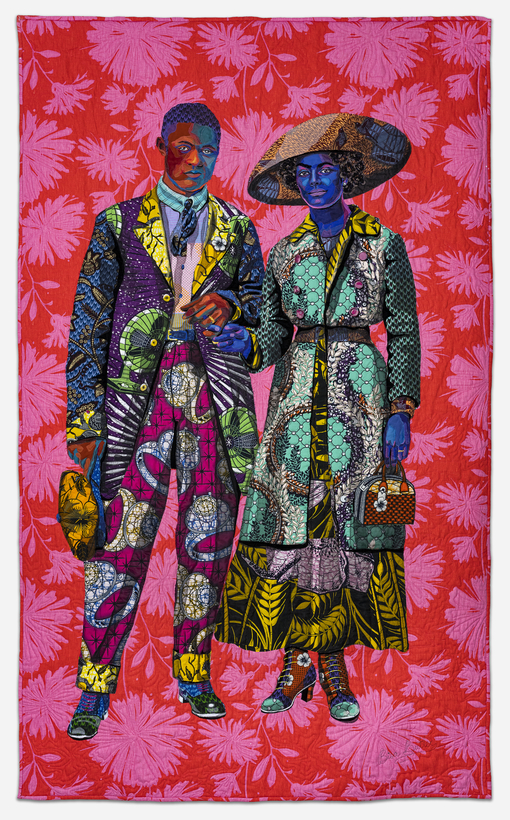

Beginning on November 16, at the Art Institute of Chicago, the extraordinary Bisa Butler has her first solo museum exhibition. Butler trained as a painter at Howard University, where many of her professors were part of Africobra, a collective that developed an aesthetic, an alternative color palette, based on the experience of Black Americans. Butler turned to fabric in 2001, when she was pregnant with her first child and worried about the toxicity of oils. She too quilts big, bold, and bright. Butler is a portraitist, and has written, “My subjects are African Americans from ordinary walks of life who may have sat for a formal family portrait or may have been documented by a passing photographer. Like the [African-American] builders of the White House, they have no names or captions to tell us who they were.”

Laura Jacobs is AIR MAIL’s Arts Intel Report Editor