I sleep nude so that I make myself believe you are here.

Many kisses, Camille.

Most of all: don’t betray me anymore!

These intimate words come from a letter the sculptor Camille Claudel wrote her mentor and lover, Auguste Rodin, from one of the many hideaways he found for them during their tempestuous, decade-long relationship. He, prodigiously talented with an imposing blond beard, and she, more than 24 years younger but headstrong with blue eyes that missed nothing, were alternately obsessed, inspired, and tortured by each other. After years of devoted work in his bustling atelier and her emergence as a significant artist in her own right, Camille, his feroce amie, was in despair—Rodin was unwilling to leave his longtime companion Rosa Breuet.

From Adjani to Binoche and Back Again

Some may recall Claudel from the melodramatic film interpretation of Isabelle Adjani as the youthful artist filling her satchel with mud and pounding it in a frenzy, or from the more restrained performance of Juliette Binoche as the older, tragic Claudel. There are also operas, musicals, ballets, plays, novels, academic studies, and potboilers that depict this larger-than-life duo.

Others are likely more familiar with the Musée Rodin in Paris, which, due to Rodin’s later support, has a gallery devoted to Claudel’s work, though the wall labels which identify her as “Sculptress, Student, Assistant, Mistress” have a sang-froid that is far from the reality of their relationship.

The youthful artist filling her satchel with mud and pounding it in a frenzy.

No such qualifiers appear in the museum that bears her name in bucolic Nogent-sur-Seine. Here Claudel is the main event, not an appendage (the Musée Camille Claudel has just reopened, one of the first French institutions to do so following the coronavirus closures).

The enterprising historic city in Champagne reclaimed its teenage resident while also paying tribute to her first mentor Alfred Boucher. After an hour’s train ride from Paris, a visitor enters a welcoming contemporary addition—attached to the revamped Claudel family home—and is met by the muscular bronzes and intricate marble and clay sculptures that mark the late 19th century.

The museum secures Claudel’s reputation as a singular talent from a rigid era when women were not allowed to tackle subjects that were considered unfeminine, or even smoke in public.

Enfant Terrible

As with her sculptures, a twisted armature underpins Claudel’s story. A wild child who often escaped to the nearby forest, she was fascinated by primitive rock formations and collected clay, defying the bourgeois expectations of her quarrelsome family and her class. Her mother was particularly resentful of her mercurial temperament and artistic ambition but her father, who adored her, recognized her talent and intelligence and made sure she was tutored alongside her brother, which was unusual for the time. Her father also reached out to the French sculptor and friend of Rodin, Alfred Boucher. After seeing her surprisingly accomplished autodidactic work, Boucher prompted the family to relocate to Paris. Claudel was enrolled in a small academy because the Beaux Arts strictly refused girls. In all ways, she fiercely resisted the life she had been brought up to acquire. Women were meant to be discreet and domestic; Claudel was neither.

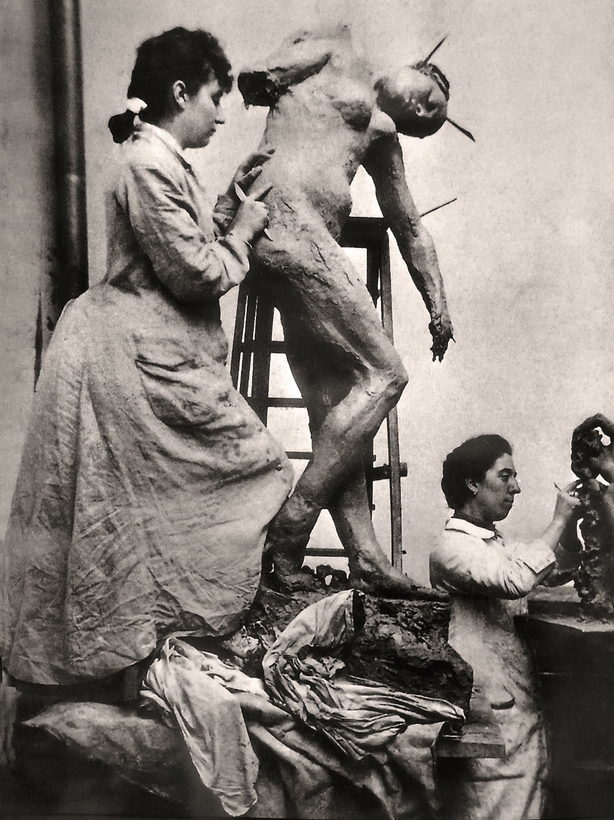

Key experiences gave shape to her life just as boulettes of clay then covered her sculpture’s coils. Boucher insisted Rodin see Claudel’s work and agreed to take her on as a pupil. Very soon, though just 19, she was first among many assistants in his atelier. Her alluring manner captivated the 42-year old-artist and she soon became his model and lover. His “dulled existence,” he confessed to her in one of many revealing letters, “burned into a bonfire.”

Women were meant to be discreet and domestic; Claudel was neither.

By circling around the pair of lover-colleagues as Rodin required of his sculpture students—a crucial final, technical step which helped bring out the movement and interiority of subjects—we see the transactional nuances of their relationship. She offered a close eye and ear on his work; that she also awakened him sexually is impossible to miss. He brought her connections to sources of funding and to the Salon where she had to be exhibited to get commissions. Despite her intense pride, and her love for him, Claudel understood that the surest path to recognition was through the patronage of a powerful man.

Their work was conjoined as closely as their bodies and though some pieces are similar, their different perspectives are telling: A man buries his head in a woman’s breast (Rodin); a man kneels and encircles a woman as she lowers her head to receive his kiss (Claudel); a woman crouches in a coil as if to protect herself (Claudel); a woman is splayed and exposed over a mound (Rodin). Her early work is often conflated with his, but her romanticism and his more flagrant eroticism—a liberty only male artists could take—is apparent.

Falling Through the Cracks

Hidden fissures began to surface in their liaison as they sometimes do in stone. Claudel agonized between her need for guidance and her resistance to being swallowed whole. She may have been the apprentice, but, cannily, she pulled away and traveled to England. Rodin was desperate. On a pretext, he pursued her—in vain. Taking advantage of the fleeting imbalance, she drew up an audacious contract which spelled out what he must do to continue to see her: she would be his sole pupil and lover, he would support her and her work, they would be married and, in an uncharacteristic nod to her bourgeois upbringing, the proof would be a professional photograph in her best dress.

In teaching her to bring out the essence of a subject, Rodin was, in a way, his own worst enemy. As she carved and molded, drawing remarkable expressiveness from inert material, it was as if she was also bringing herself fully to life. Claudel was not content to stay in her box.

In teaching her to bring out the essence of a subject, Rodin was his own worst enemy.

“Have pity, cruel girl, I can’t go on,” Rodin wrote. Despite his passion and admiration for her, the pre-nup was consigned to oblivion. Caustic cartoons she sent to him, depictions of a hapless Rodin trapped by Rosa, projected her anger. Another more poignant missive from her brother Paul, who had become an influential—and largely absent—poet and diplomat, reveals that Claudel also had an abortion.

Determined to assert her artistic and spiritual independence, she fled their folie a deux, even though leaving Rodin meant certain financial instability and the loss of critical attention. The Claudel specialist Anne Riviere, in a companion film at the museum, says, “In this desire to escape…his footprint, Camille Claudel invents…a way of making small sculpture big.” She began using rare materials like onyx. “It’s not at all Rodin,” Claudel proudly wrote Paul.

Losing Her Marbles

Though she kept the studio Rodin rented for her—money was indeed a problem—her new, intimate style was on display. Swirls and waves surround nude women frolicking or gossiping. In La Valse, a couple entwined in each other dance. Despite her repeated ardent supplications, the ministerial authorities refused marble for this piece, citing its display of “sexual organs which are too close.” A work like this was a slap in their faces.

She returned to the larger work, concerned with being marginalized as “decorative.” Her compelling Age of Maturity details a young woman grasping in vain for a man in the clutches of an older woman. The Goodbye, a woman struggling to escape a block of marble, is Rodin’s answer. These allegorical pieces show that Claudel and Rodin were still emotionally if not physically attached. Her Clotho, a mythological crone with tangled dreadlocks, reflects her increasingly precarious state of mind, the high-strung young girl now a woman showing clear signs of erratic behavior. Though Rodin agreed not to further agitate her by seeing her anymore, he worked tirelessly behind the scenes to help her, a ringmaster bereft of his high-wire act.

But still the commissions did not come. With only the rare show by her loyal dealer, she became ever more paranoid, fearful that Rodin and his allies were stealing her ideas. She moved again and barricaded herself, not bathing, barely eating, muttering as if possessed. She burned his letters. She destroyed many of her sculptures.

A work like Claudel’s was a slap in the faces of the authorities.

The neighbors complained. Fearing she would harm herself—and ruin the family reputation—Paul had her forcibly committed. Her father was devastated, her mother relieved of the burden. After a stay in an asylum near Paris, with war coming, Claudel was moved to another facility near Avignon. She implored the family to let her come home, or, failing that, to move her closer to them as even Paul hardly visited. But there was never an adequate response. And she had lost any meaningful advocates. Claudel spent a total of 30 years in close confinement, not sculpting, a sentence considerably more violent than she was. It’s as if the art had somehow contained the madness. She died, alone and abandoned, at 78.

Some think Claudel a victim of Rodin, others of a neglectful family, still others of her instability. Unquestionably, Claudel was a victim of her time. Just a few years after her death, in 1943, there was an explosion of female artists making their own way.

For too long, Claudel’s artistic reputation, much like Vincent van Gogh’s, was muddied by scandal and the tragic dénouement. According to Odile Ayral-Clause, a biographer, “The critics who condemned her for not being able to create a style [distinguished enough from Rodin’s] failed to understand that her battle was focused in a different direction.” The Musée Camille Claudel instead celebrates her native talents, novel choices, and incipient feminism. In Nogent, Claudel is surrounded by vibrant flowers, rushing waterfalls, charming allées. In Nogent, all her life is before her.

Patricia Zohn is an Editor at Large for Air Mail