We want our artists to grow old, because their journeys inform our own. It isn’t just the body of work—the first historic strokes and sparks to the last autumnal musings, wise yet also light with liberation. The arc of the life itself is instructive. This year, the 350th anniversary of Rembrandt’s death, has seen numerous facets of the master’s work celebrated in exhibitions all over the world. At the same time, we are reminded of Rembrandt’s compelling trajectory: a steep climb to fame and fortune, a perilous drop out of fashion. Refusing to flatter the powers that be, his work grew only more profound. There is a lesson in that.

Next year, 2020, marks the 250th anniversary of Beethoven’s birth. His arc of early–middle–late curves over the world like a crown of freedom. There are even arcs within a single work, as we see in various upcoming productions of his lone opera, Fidelio, which premiered in three separate versions over nine years. Beethoven lived to age 56, not bad in those days. Mozart, he was stolen away at 35, in 1791. We can, of course, divide his oeuvre into periods, and then proceed to label his last works “late”—but are they? Both Cosi fan tutte (1790) and Die Zauberflöte (1791) delve into the challenges and meanings of monogamy, not usually a late-period subject. Mozart wasn’t done—despite the portent of his unfinished Requiem (1791). He was cut short. What would have come next?

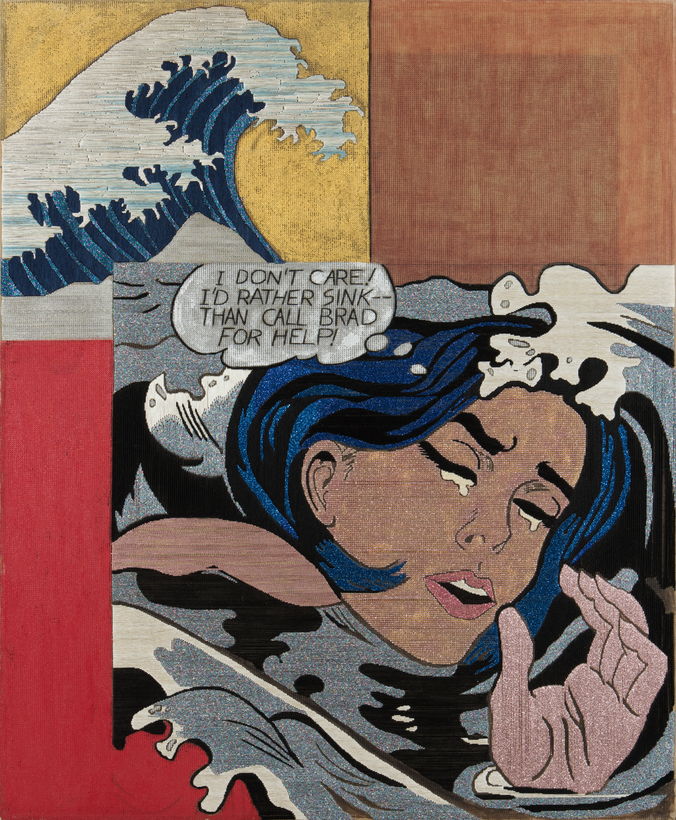

This question haunts all premature deaths. When the subject is a young artist, having made their first fresh impressions upon the culture, the question is one for public consideration. The artist Keith Haring, whose reverberating work is now on at the Tate Liverpool (through November 10); the tapestry artist Nicolas Moufarrege, whose more rarified medium is presented at the Queens Museum (starting on October 6); and the Puerto Rican fashion illustrator Antonio, whose continuing influence is examined at the Phoenix Art Museum (through January 25)—all three were lost to the epidemic that swept away a generation just coming of age. Each of these exhibitions leaves us wondering, What would their art be telling us now?

Mozart was cut short. What would have come next?

In Chicago, at Wrightwood 659, the surrealist paintings of Tetsuya Ishida have their first and only showing in America, in the exhibition “Self-Portrait of Other” (opening October 3). Ishida has a cult following in Japan, where, in opposition to Hello Kitty cuteness and anime energy, his young male everyman embodies a stagnant economy of lost dreams. Drained, isolated, morphologically fusing with urban structures, this person—his personhood!—is silently disappearing. Ishida was struck by a train in 2005, when he was 31, a death that may have been a suicide.

At the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, “Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation” is on view through April 5, 2020. All of Woodman’s work is early: this brilliant American photographer took her own life at age 22, in 1981. Circling in on the years 1975 to 79, the Denver exhibition includes over 40 formative photographs, never before seen, as well as candid shots of a joyful Woodman. Because of her suicide, there’s an impulse to interpret her imagery, its pervasive sense of a ghostly presence, in just one way—darkly. “Don’t,” this exhibition take pains to say.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, is hosting the debut presentation of a series by one of America’s greatest artists, now 89, Jasper Johns. It’s called “100 Variations on a Theme” and it includes 100 prints—made over 10 days in 2015—with elements limited to handprints, stenciled numbers, leaves, and string. What is more autumnal than fallen leaves, their veins so like the creases, lifelines, in a hand? A leaf falls upon the ground. The artist’s hand falls upon paper. Unlike the leaf, the artist’s work lives on.