Nothing about my childhood portended a career in war journalism. As an only child rattling around the top floors of townhouses on the Upper East Side and Belgravia, with an ever-revolving door of nannies, the pain and privation of war could not have been more remote.

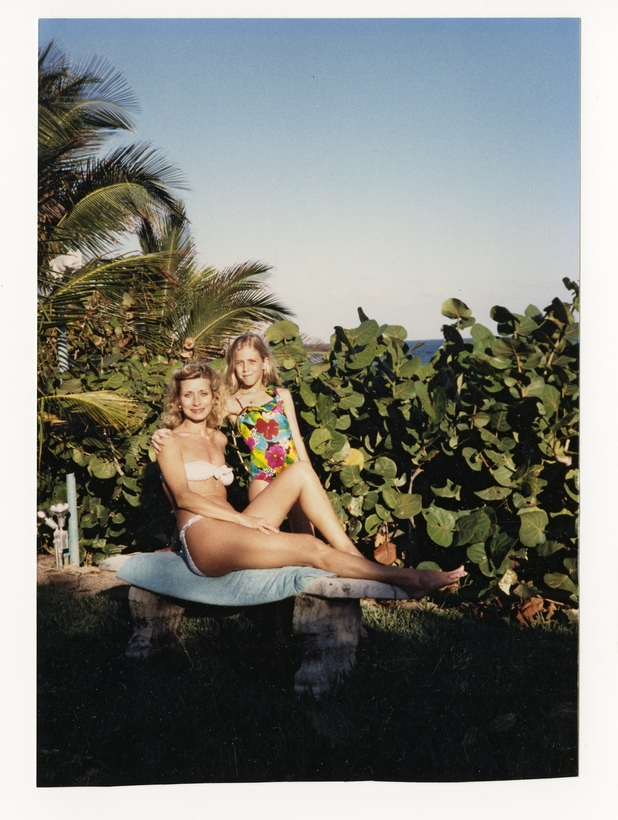

My workaholic American mother was the self-described “architect” of my life. She organized for me to be ferried from ballet to ice-skating to tennis and piano lessons. She had, and still has, a strong opinion about pretty much everything, from her disdain for sunsets—“they’re corny and boring”—to her love of Walgreens—“America has the greatest drugstores on earth.” Her professional life has been dedicated to creating beautiful houses. “I’m a spatial genius,” she often says. Modesty has never been her strong suit.

My mother was always very candid about what she expected from me. “I will always give you freedom and money, as long as you get straight A’s and look beautiful—that’s all I ask.” At the age of ten, I was shipped off to a dismal boarding school in the British countryside with vague assurances that it had an excellent academic record. “At least your friends will be smart. My social European girlfriends all went to finishing school and are complete twits.”

While most of my classmates were dropped off with engraved stationery and tuck boxes, I was given packs of acidophilus tablets and Ryvita crackers with a stern warning that the Brits don’t have any fiber in their food. It may not sound like the training of a foreign correspondent, but my upbringing certainly taught me to be adaptable, self-reliant, and curious.

During the summers, my mother and I would fly to Hong Kong to visit my father, a British investment banker working there at the time, and we would travel around Asia. On these trips, she’d offer a seemingly endless stream of instructions and unsolicited advice.

“Always eat airplane food, you never know when you’re going to get stuck somewhere.”

“You should hand wash your underwear in hotels. It’s what ladies do.”

“Never go anywhere without undereye concealer.”

“The secret to a great martini is the vermouth.”

“Always carry Benadryl with you.”

And, most importantly, ”NEVER CHECK IN LUGGAGE!!”

“At least your friends will be smart. My social European girlfriends all went to finishing school and are complete twits.”

At the time, I found these diatribes rather tedious, but years later, I concede that this was all very solid advice. I have relied on my mother’s wisdom when covering conflicts and crises around the world (particularly when I forgot to pack a spare pair of underwear to cover the tsunami in Japan) and I now impart it to younger journalists who are starting out.

My mother has always been a huge supporter of my career. A voracious consumer of news, she can stay in bed for hours in the morning reading every newspaper in the U.S. and U.K., with CNN blaring in the background. When, as a teenager, I insisted that I wanted to be an actress, she would shake her head and say, “You’re too smart—you’ll grow out of it.” While she is passionate and knowledgeable about many of the stories I have covered, particularly Syria, she also understands instinctively that television is fundamentally a superficial medium. Even today, she scrutinizes every single one of my live shots and immediately pecks out an email with her forefinger detailing her observations.

“Don’t lose too much weight but for God’s sake don’t get fat—you look better when you’re bony.”

“Wear your hair up.”

“Orange is not your color… nor is green—you look sickly.”

“Don’t stoop.”

“Don’t be phony.”

“Be careful of sounding too nasal.”

As I noted in a speech at my wedding, “Those girls in Toddlers and Tiaras have got nothing on me.”

When I had finished writing my book, On All Fronts: the Education of a Journalist, I gave it to my mother to read. She insisted that she didn’t even recognize the descriptions of her—“It’s like you’re describing a fictional character”—though I could tell she was secretly pleased at being featured so prominently in descriptions of my early life. She did, she said, have one serious request.

“I have given it some thought, darling, and I do think you should dedicate the book to me.”

Of course, I did.

Clarissa Ward’s On All Fronts: The Education of a Journalist is out now from Penguin Press