When the director Brett Morgen started making his David Bowie film he says there was a clear set of rules: “No dates. No biography. No facts.” Blockbuster biopics are expected to fit a certain mold — like Freddie Mercury’s romp Bohemian Rhapsody and Baz Luhrman’s lavish Elvis. A Bowie version of that would make millions. But Moonage Daydream, the first official posthumous documentary about Bowie since he died in 2016, is different: a beautiful, dreamlike 180-minute epic — one Morgen discussed with those close to the star.

Bowie’s legacy has until recently been carefully handled — as one of history’s most singular artists, he was in charge of his image to the end and had clear ideas about how he wanted to be remembered.

Yet with millions of dollars at stake, Bowie’s control of his afterlife machine may be slipping, in an age when there are infinite ways to conjure a lucrative legacy — from Abba-style hologram tours to jukebox biopics and TikTok (to mark what would have been Bowie’s 74th birthday last year, his music went on the Gen Z platform of choice).

There was a clear set of rules: “No dates. No biography. No facts.”

“There’s a myriad of opportunities,” says Guy Moot, the chief executive of Warner’s publishing arm, who paid the Bowie estate $250 million for control of the back catalogue in January. By April Sound and Vision was the soundtrack to a B&Q advert, while Adobe Photoshop has bought the rights to name “make-up brush” tools after Bowie’s hits. That is not what he wrote “Oh! You Pretty Things” for.

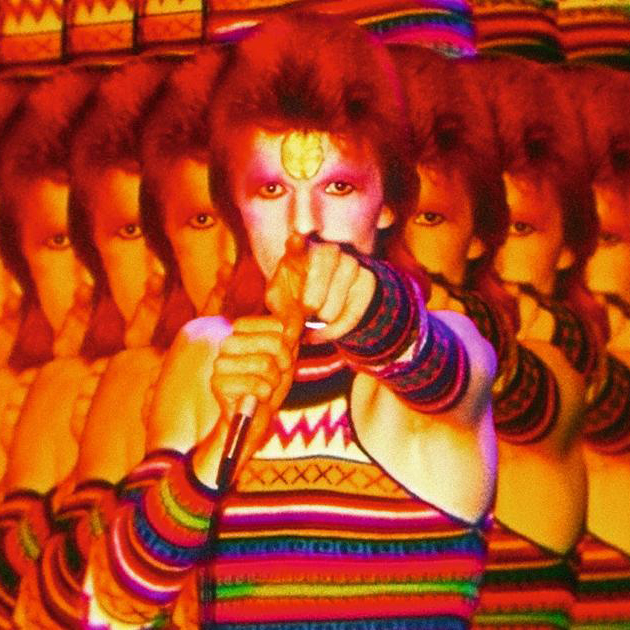

Moonage Daydream, named after a track on the Ziggy Stardust album, stands apart from all this. I seek out the verdict of a man whose opinion Bowie would value, the pianist Mike Garson, a collaborator for three decades, including on Aladdin Sane. Nobody played on stage with Bowie more often than Garson, including the breathtaking Glastonbury headline slot in 2000.

A gentle and kind man, Garson, 77, welcomes me into his home in the plush Los Angeles suburb of Calabasas, where the walls are lined with Bowie photos and posters. “I think he would like this film,” he says. “Three quarters of it he would really enjoy.” And what quarter would he not like? “Sometimes when it’s over-the-top flashy with a million images? It felt a little much.”

Garson loved the film. It is, he thinks, an ideal way to sustain the legacy of a man who prized creativity above success — although, Garson adds, Bowie enjoyed the latter. Not that he hasn’t been tempted to cash in himself. In the six years since Bowie died, the estate (headed by Bowie’s longtime manager Bill Zysblat, it consults Bowie’s widow, Iman, and son, Duncan, on big decisions) has rebuffed an offer Garson made to play in a Bowie hologram show in Las Vegas. It also refused him permission to use Bowie’s image for a cover-song band he plays in with other onetime collaborators.

“David didn’t approve of a tribute band,” Garson explains. “It has always been hard work [with the estate]. The Vegas offer got shut down quickly because David would never have wanted it. But when I spoke to Bill a year later, he said, ‘These things may loosen up but I’m still respecting David’s wishes.’ David didn’t want a Queen-type biopic — he was very insistent to Bill. But there will be a point in, say, ten years’ time when Bill retires and maybe [the family] say, ‘Let’s do it.’ Because there is a story to be told.” It will probably be called Starman.

And telling these stories is profitable. Bohemian Rhapsody took nearly $1 billion at the box office. Elvis has already made more than $250 million. More important, Spotify monthly listeners for Queen shot up to the 40 million mark after the film was released, bringing new revenue streams as original fans fade away.

Adobe Photoshop has bought the rights to name “make-up brush” tools after Bowie’s hits.

I meet Morgen, Moonage Daydream’s director, in his office in L.A. He is a tall man in a smart suit with a bright tie and bright socks. The room is full of Bowie memorabilia. He shows me a huge file from the archive labeled “74-76”, one of many, that is packed with lyrics, drawings, film scripts. It is fascinating. “Bowie is mysterious,” Morgen says. “He’s sublime.”

Morgen has history with musical icons, having made documentaries about the Rolling Stones and Kurt Cobain, but this is his biggest by far. The film took five years and he is thrilled that his job was to sift through Bowie’s personal effects for that long. Born in 1968, Morgen has been a fan since Scary Monsters.

He met Bowie in 2007, when he pitched an idea that would have involved the singer performing for days on end. It did not happen, but after Bowie’s death Zysblat and Morgen discussed how to treat the archive. Bowie told Zysblat he did not want a traditional doc, so Morgen was the ideal man for the job. The director’s model for the documentary was Disneyland — like that park’s best roller coasters, he wanted an immersive ride of Bowie’s life. It was a pitch the estate liked.

The final cut of Moonage Daydream is, mostly, what Morgen initially promised. Less fact, more feelings. “If you go to the movie looking for stories about Lou Reed or Iggy you might be disappointed,” he says.

Bowie is the only talking head, taken from television footage, while his first wife, Angie, and Duncan are not mentioned. That said, the most moving part delves into Bowie’s mother and her indifference to her son. It then segues into his elder half-brother, Terry, whom Bowie idolized but who was hospitalized for years after a schizophrenia diagnosis. Terry’s mental illness scared Bowie, given how much his own mind wandered. It is powerful cinema.

“I arrived at a point where the film needed biographical sprinkles,” Morgen admits. The relationship Bowie had with his mother and brother informs the theme of isolation in the singer’s work, while the editorial reason for not mentioning Angie or Duncan is bluntly that the film is about Bowie’s artistic journey and neither, Morgen says, had much impact on his work. Iman, though, is featured because Morgen believes her arrival, in 1990, marked a great change in Bowie.

“My perception was that everything post-Iman was very comfortable,” he explains. “I think he plateaued, but that is a positive because he struck a balance between art and life where work wasn’t 100 per cent of everything. He’s not going to put himself in the fire, so to speak. That’s why, when he meets Iman, my narrative ends.”

What is the estate’s reaction to the finished film? “Unbelievably supportive,” he says. “But there were probably a couple of things they wished I didn’t do.” Such as? “The biographical stuff. The things about his family were not something David liked talking about much, and I felt I was exposing myself by including them because I was breaking a covenant. The moment that you introduce one element it raises the question of why don’t you mention this and that. That was something I wrestled with for several years.”

The movie does not, for instance, tackle accusations that Bowie had sex with teenage and even underage girls. It is deliberately, buoyantly hagiographic in an era when, on the internet, viewers have access to everything about a celebrity at their fingertips — positive and negative.

“I wasn’t trying to cleanse,” Morgen says. “I read somewhere that it looked like I hadn’t mentioned drugs because the film is sanctioned by the estate, but, to me, Bowie seemed pretty ripped on drugs in the 1970s — I didn’t need to state it. This is constructed with awareness that the public has access to information and there will never be a definitive portrait: it’s not possible. Also it is told through his words so is limited by how he perceived himself. It’s consciously not about David Jones and I think what you’re referring to [sexual misconduct] has more to do with David Jones and less to do with Bowie.”

The movie does not, for instance, tackle accusations that Bowie had sex with teenage and even underage girls.

(Sweetly, when I ask Garson whether, while watching Moonage Daydream, he saw Jones or Bowie on screen, he smiled, “He was just my friend called David.”)

Morgen suffered a heart attack while making the movie, but says the job is not what threatened his life — rather, Bowie saved him. The more he went through the archive, the more musings he found on mortality. It was then that he decided to go further than Disneyland — he wanted something life-affirming.

“After my heart attack I found tremendous comfort in Bowie’s messaging,” Morgen says. “What comes across through listening to him is this idea that life is not a search towards something but about this moment. That was the lesson I took from David. Life is a blink of an eye, so make the most of it.”

“Look up here, I’m in heaven,” Bowie sings on “Lazarus,” the last single released in his lifetime. It was an unprecedented track from a last album, Blackstar, that saw the artist facing his death. His legacy now, though, is in the hands of others.

Earlier this year his music was made available for a Peloton fitness routine. One DJ invited to remix a track for the collaboration said: “I chose “Let’s Dance” because it’s a celebration of music and movement — just like Peloton!” Moonage Daydream, on the other hand, I think, continues what he set out to achieve in his work, but that will not always be the case. What would Bowie think, one wonders, looking down from heaven?

Moonage Daydream is playing now in cinemas across the U.S.

Jonathan Dean is a senior writer at the Sunday Times Culture section and the author of I Must Belong Somewhere: Three Men. Two Migrations. One Endless Journey