At first there are two “essays,” I’d call them. One is by Paul himself, and the other is by the American historian Jill Lepore. Both are wonderful and bring one to that time again, or for the first time.

For me, it’s “again,” and two dates stand out as markers.

I am two years older than Paul, and I was in my early 20s, working for Irish TV in Dublin, on November 22, 1963, when J.F.K. was killed. Although abroad, as an American I felt the same sickening shock, and the heavy, out-of-sync depression that would not go away. I thought of the Great Wounded Beast of America brought to its knees, and not for the first or last time, by a gun.

On February 9, 1964, the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan’s TV show, watched by 73 million people. They sang “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and reached out theirs. Love was offered, love was taken. Joy had come upon the land again, and Beatlemania had officially begun.

George, 20, Paul, 21, and John and Ringo, both 23, had grown up in rough-and-tumble, badly-bombed-in-the-war Liverpool, which always managed to give its citizens a jolt of its own ironic sense of humor.

On February 9, 1964, the Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan’s TV show. They sang “I Want to Hold Your Hand” and reached out theirs.

Their musical and life education continued in the red-light district of Hamburg, where the Beatles played in strip clubs, disreputable bars, and smoky drunken dives for eight hours or more every night, kept awake by adrenaline and whatever else they could find.

And so it was these three, Paul, John, and George, plus Ringo—who joined just before the spotlight finally settled on them, like the ball on the roulette wheel—who changed the world, who were anointed with a degree of fame which is not imaginable anymore.

Nowadays, with so many links to click and sites looking for your attention, it is possible to be little-known today, somewhat famous tomorrow, very famous the next day, less famous the day after that, and forgotten by the end of the week. Replaced by a replacement.

Whereas in the 1960s, there were six buttons that would have to light up for you to be really famous: movies, television, radio, newspapers, magazines, and records. That was it—nothing extra, nothing more. And once it happened, it was agreed by all concerned that to keep it like that was a good idea—good for the purveyors, good for the celebrated.

Joy had come upon the land again, and Beatlemania had officially begun.

The Beatles were very ambitious, hardworking, funny, tough, insular, and eager to be recognized for what they were—a great rock ’n’ roll band with great songs, songs that would endure. And so, since America was the big prize, a Hollywood dream for teenagers in leather jackets in Liverpool, it is only right that America, with its 73 million fans, was where the dream was realized.

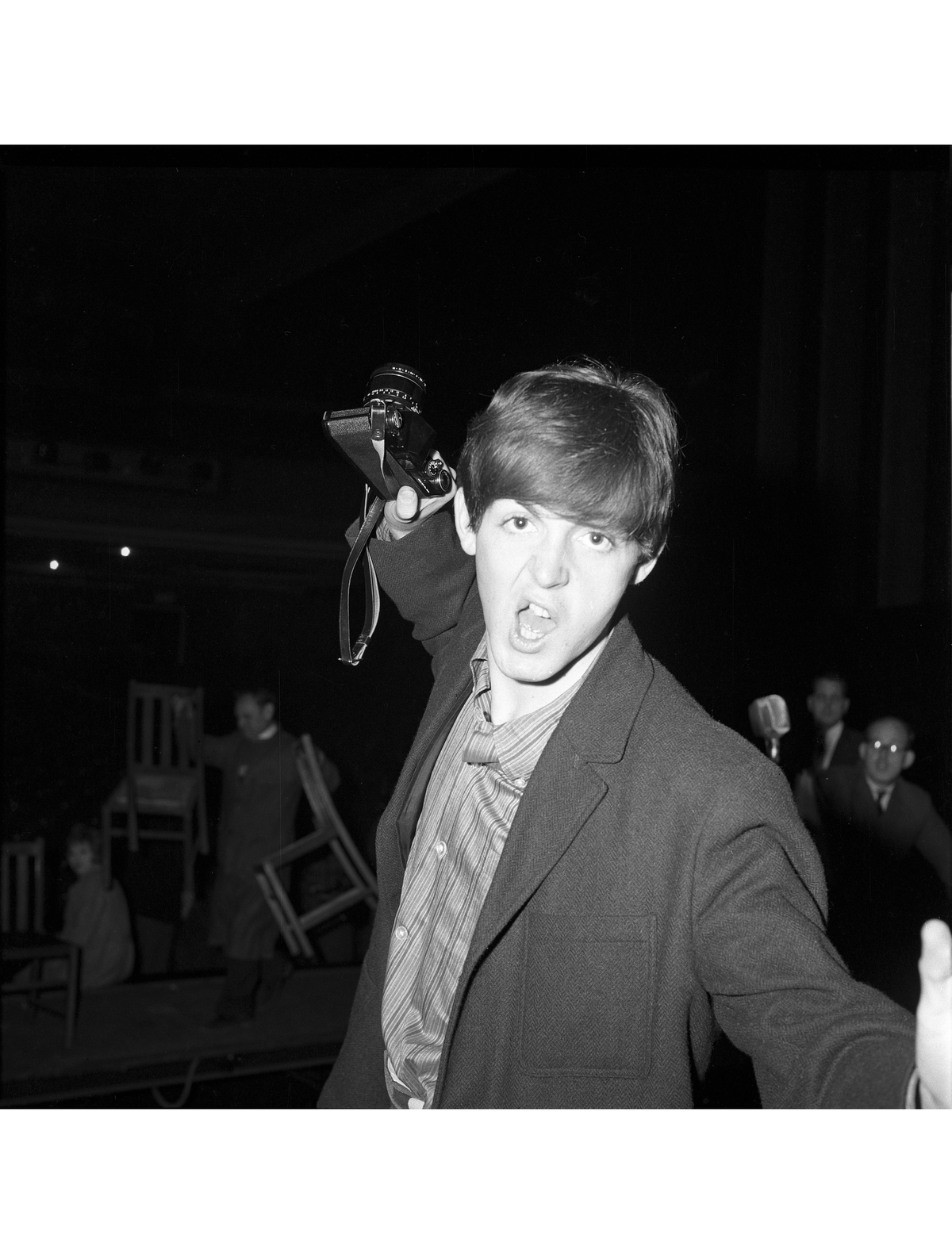

And Paul had a camera.

He and the other Beatles had purchased cameras to take souvenir snaps on—whatever caught their attention. But Paul held onto his longer, and his Pentax photographs of 1964, collected in this new book, Eyes of the Storm, are a small treasure.

And Paul had a camera.

When he first came to London, Paul lived in the house of his girlfriend at the time, Jane Asher, and her family. And he took some affectionate photos of her, wishing he had color film to capture Jane’s “copper-colored” hair, as he described it.

Then there is a photograph I want to point out, taken from an upstairs window at the Ashers’, looking across to the backs of the houses across the way. Three doors with chipped white paint face onto their fire escapes. There’s another white window over to the right, and then two smokestacks framing the inner image—a frame within a frame. I bet it was a Sunday afternoon. Sunday afternoons in London in the mid-60s promoted loneliness. A time and a place on a particular day, and Paul got it.

Paul took pictures of the other three, and of the Liverpool crew. Brian Epstein, the man who “discovered” them. Mal Evans, their road manager, tall, strong, and gentle, but who could certainly look like a deterrent. Neil Aspinall, who’d begun driving the Beatles plus instruments (and drum kit) all together in the back of his van, and finished his career running Apple, the Beatles’ company.

Liverpool, Paris, London.

Then: February 7, on Pan Am Flight 101. The rendezvous with destiny. Epstein, with an enigmatic but confident look. George sleeping; John perched on the arm of a seat, wearing his glasses, looking back toward Paul.

Then the crowds, the people barriers put up by New York’s Finest. An extraordinary shot of people running in traffic, ahead of cars and taxis on West 58th Street heading toward the Plaza, taken from the back of a moving car.

Washington. A few days off in Miami, except for another Ed Sullivan Show. Paul using color film for the first time. A shot of George, like a character in Le Mépris (Contempt), being served a drink by a young woman identified only by her yellow bathing suit.

A photo which might be of special note is one that Paul took out of the side window of their car, at a motorcycle policeman accompanying them. What Paul focuses on is his gun belt with bullets in it and a revolver in its holster. English policemen in those days did not carry guns, which generally made you feel safer in the street. Even today, firearms are issued to only specially trained officers.

I find myself describing photographs, which is easy to do, in a way, but not really satisfying, for me or for the reader, when the photographs are there, and the years, and the gone time, the glorious time, the time to come, the memories, are right there in Paul’s book.

1964: Eyes of the Storm, by Paul McCartney, will be published on June 13 by Liveright. An accompanying exhibition will go on show at the National Portrait Gallery, in London, beginning June 28

Michael Lindsay-Hogg directed the Beatles’ videos for Rain, Paperback Writer, Revolution, and Hey Jude, as well as their 1970 documentary, Let It Be