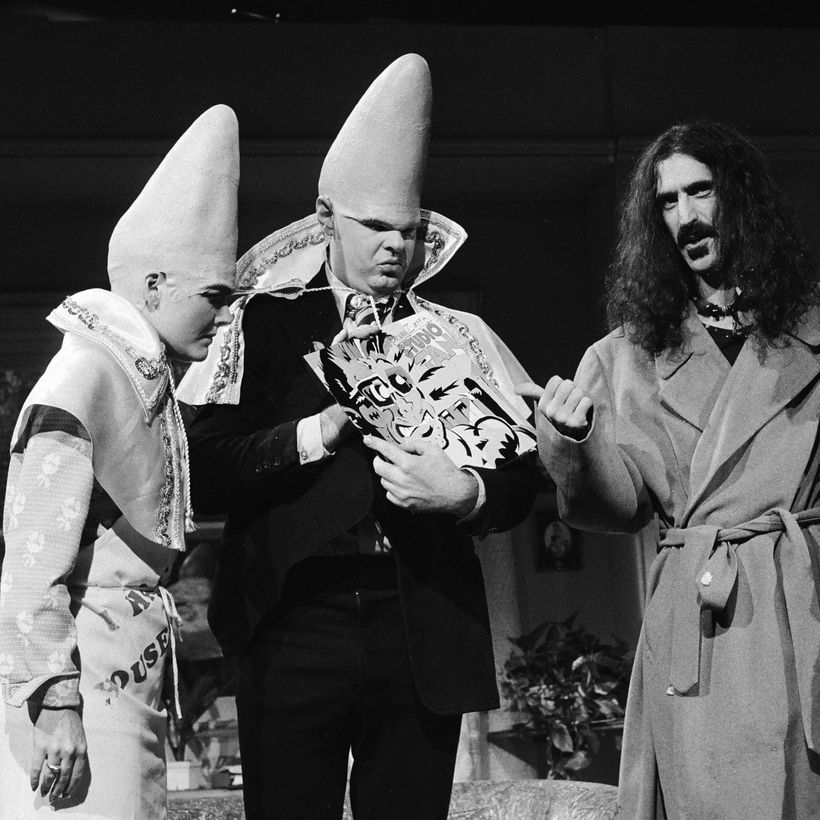

When Alex Winter was 13, he watched Frank Zappa—guitar virtuoso, counterculture avatar, and beak-nosed provocateur behind such cult-classic, entirely uncategorizable albums as Hot Rats and Weasels Ripped My Flesh—host Saturday Night Live. The combination of rock’s gonzo satirist and television’s upstart sketch-comedy show seemed like a no-brainer. But Zappa’s October 1978 appearance was perhaps the biggest hosting debacle in the history of S.N.L., as the contrarian musician, true to form, refused to play by anyone’s rules but his own—calling attention to the cue cards, going out of his way to be terrible in a Coneheads sketch.

Winter was fascinated by this late-night-television train wreck, with Zappa as self-appointed Casey Jones. (For his efforts, or lack thereof, Zappa, who died in 1993, was banned from the show for life.) Recalling the occasion recently, Winter said, “I thought, There is so much more to this person than the weirdo who plays guitar.”

Forty-two years later, Winter, the prolific documentary maker who played William “Bill” S. Preston, Esquire, in the Bill & Ted movies, is showing the world just how much more there was to Frank Zappa. He is the director of Zappa, a stylish, immersive, eye-opening, and, at times, uproarious two-hour documentary about the life, times, and artistry of the eponymous musician, out now in theaters and available to stream.

“I thought, There is so much more to this person than the weirdo who plays guitar.”

Zappa is no mere Behind the Music. Winter was determined to make what he calls “the Tom Wolfe-novel documentary of Zappa—the fully dressed man, from top to tail,” and that’s what it is. He gained the trust of Zappa’s now-late widow, Gail, and thereby access to The Vault, a vast subterranean archive of all things Zappa, which Winter helped preserve with a record-breaking Kickstarter campaign. He then plumbed it to create a movie whose antic visuals, including claymation by Zappa associate Bruce Bickford, are, well, Zappa-esque.

Winter’s Zappa contains almost unfathomable multitudes. He’s a boy who dreamed of growing up to be a chemist and began making gun powder at age six (his father taught metallurgy). He became a skilled composer and arranger before graduating from Antelope Valley High School. He enjoyed a brief career as a commercial artist and copywriter. And then, in the mid-1960s, he took over the Sunset Strip with his Mothers of Invention, a musical troupe that was equal parts R&B and avant garde.

Marcel Duchamp once called the L.A. assemblage artist Ed Kienholz “marvelously vulgar” and it’s tempting to say the same thing about Zappa. He played the line between high-culture sophistication (his compositions were indebted to Stockhausen and Varèse) and lowbrow sleaze like an electric Paganini. He was a withering parodist who tweaked rock’s ultimate sacred bovine, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, as We’re Only in It for the Money. When Zappa took aim at a target—whether it be pretension, phoniness, hypocrisy, complacency, commercialism, or, in the 1980s, efforts by the Parents Music Resource Center to mandate a rating system for CDs—he wanted to blast it into oblivion. You can’t help but wonder what he would have made of the 21st century.

Zappa was a withering parodist who tweaked rock’s ultimate sacred bovine, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, as We’re Only in It for the Money.

As the various collaborators Winter interviewed attest, Zappa, whose output veered from rock to jazz to classical and back again, was also a workaholic perfectionist with martinet tendencies—an autocrat with a Gibson SG. Yet he had the paternal glow and moral rectitude of a scoutmaster. Zappa hated drugs and his house in Laurel Canyon, where he doted on his four children, became a welcome center for guitar-strumming bohemians. (Pamela Des Barres calls him “the pied piper of Laurel Canyon.”) Before Zappa died of prostate cancer at the age of 52, in 1993, Czech president Václav Havel made him a kind of cultural attaché; as such, Zappa found himself a symbol of Eastern Bloc liberation, and, by extension, of freedom itself. All this for a guy who dispensed such musical wisdom as “Don’t Eat the Yellow Snow.”

Winter’s own favorite Zappa is The Yellow Shark, an orchestral work released just before its creator’s death. “Frank Zappa was a man actively engaged with his times,” Winter said. “And he was far more complicated, interesting, and dynamic than people realize. That’s why I had to make this movie.”

Zappa is available to stream on Amazon Prime

Mark Rozzo is an Editor at Large for AIR MAIL