“Nature educates us into beauty and inwardness,” said the photographer Karl Blossfeldt, “and is a source of the most noble pleasure.”

Blossfeldt began making his own cameras in 1899, while working as a teacher at Berlin’s Kunstgewerbeschule (Institute of the Royal Arts Museum). At that time he also began photographing flowers in black and white, to teach his students the intricacies of flora. He wanted them to understand that all art came from nature, and that flowers could be used to express any emotion—joy, sadness, love, death.

Blossfeldt had predecessors. Earlier in the century, in New England, Edwin Hale Lincoln brought native plants to his studio, where he photographed them with a box camera, and then returned them to the forest. He left us a portfolio of 400 magnificent platinum prints. Similarly, Henry Fox Talbot created photograms in the 1830s. And in the 1840s, the botanist Anna Atkins began producing her shades-of-blue cyanotype impressions of British seaweed and flowers.

Imogen Cunningham’s glacial close-ups, Man Ray and his sci-fi rayographs, Irving Penn’s studies of poppies and roses, Robert Mapplethorpe’s aggressive erotic forms—the 20th century saw all these photographers zooming in on flowers.

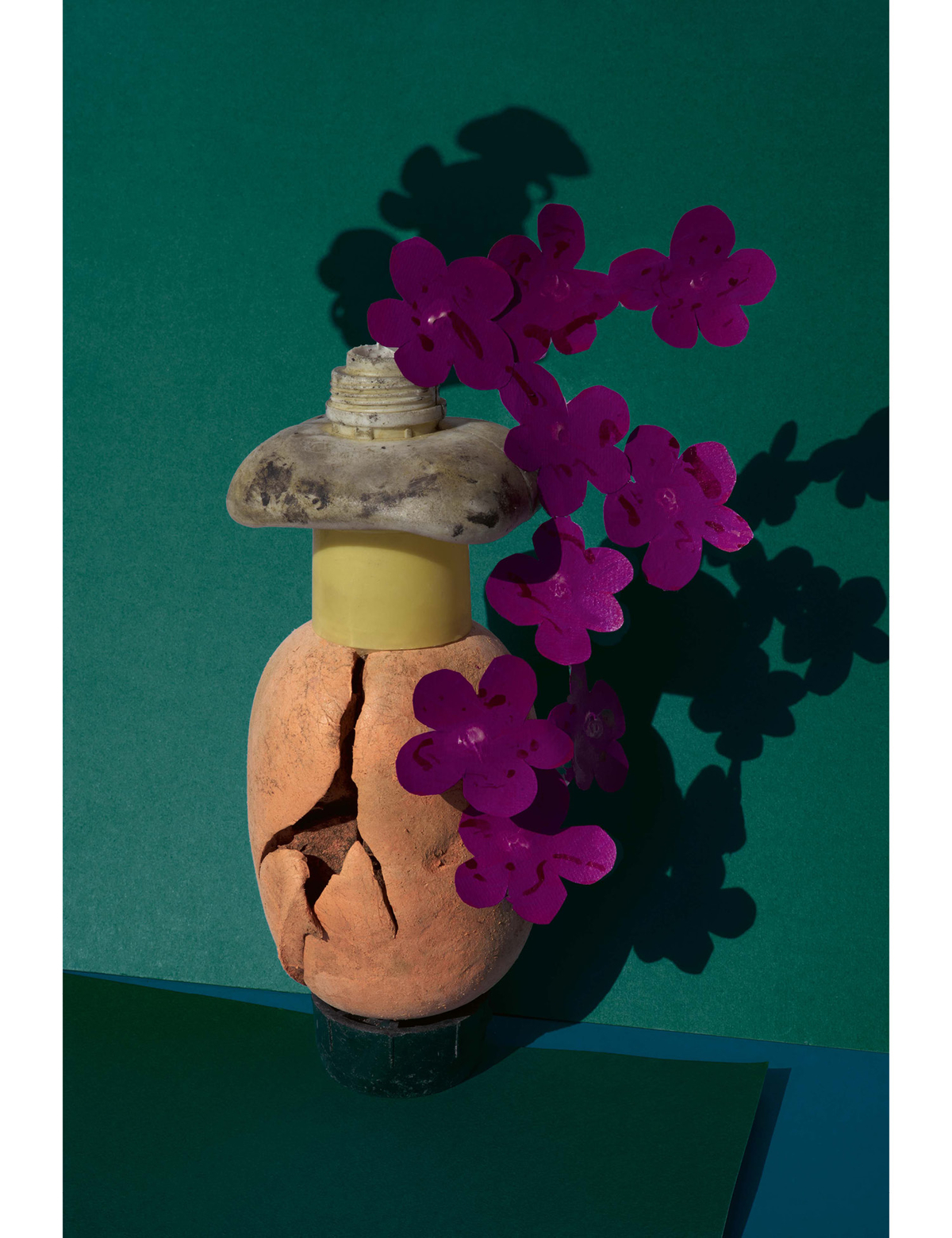

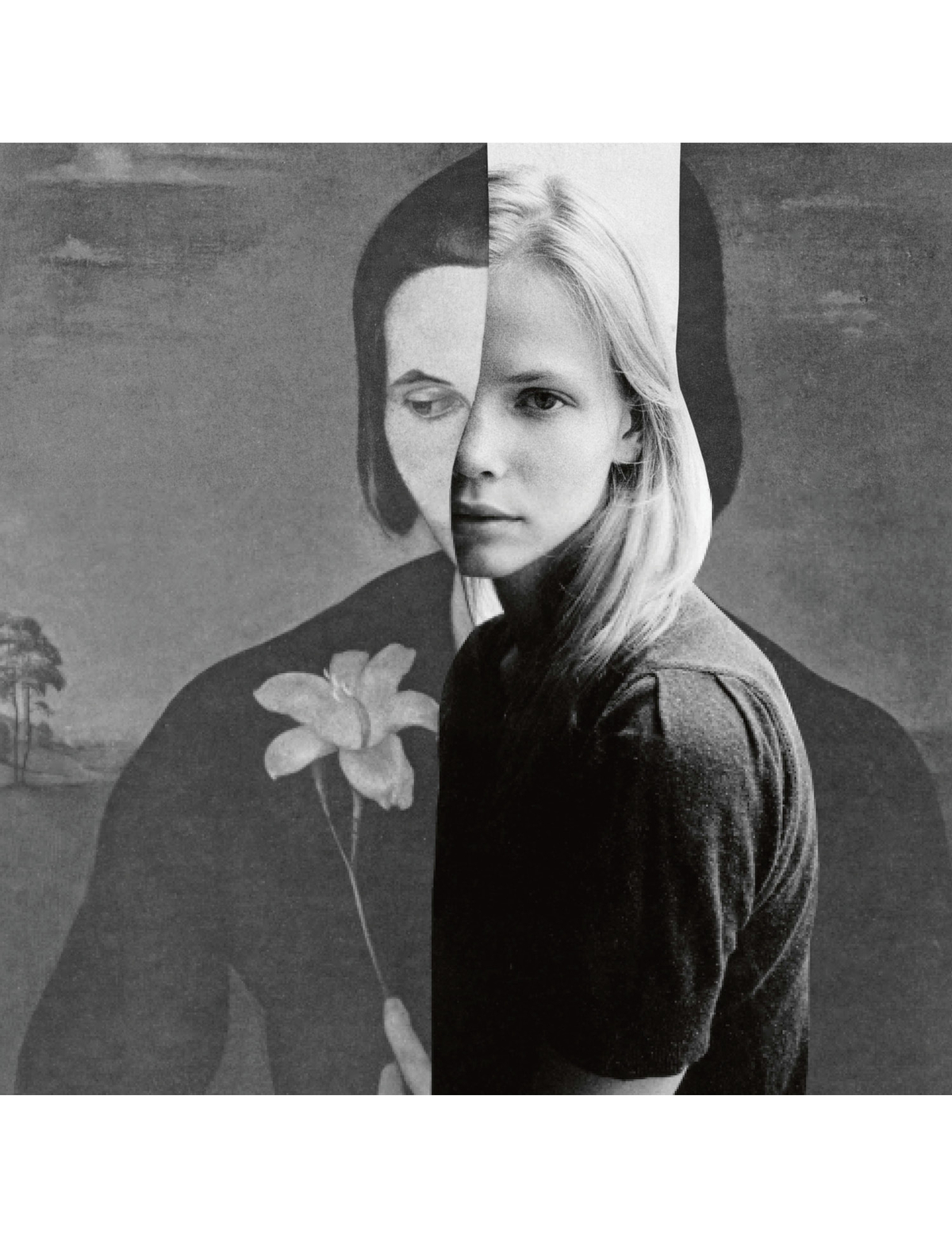

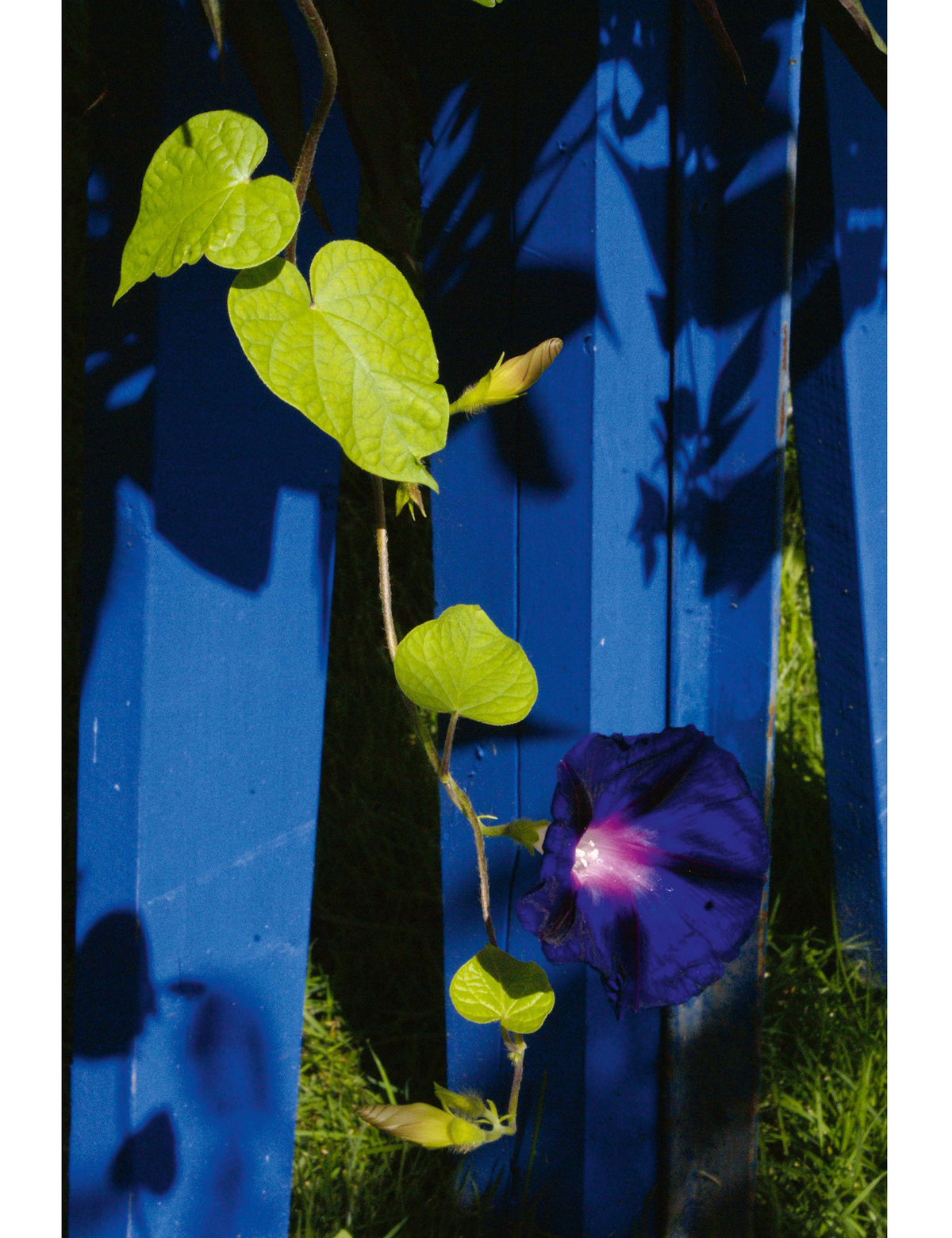

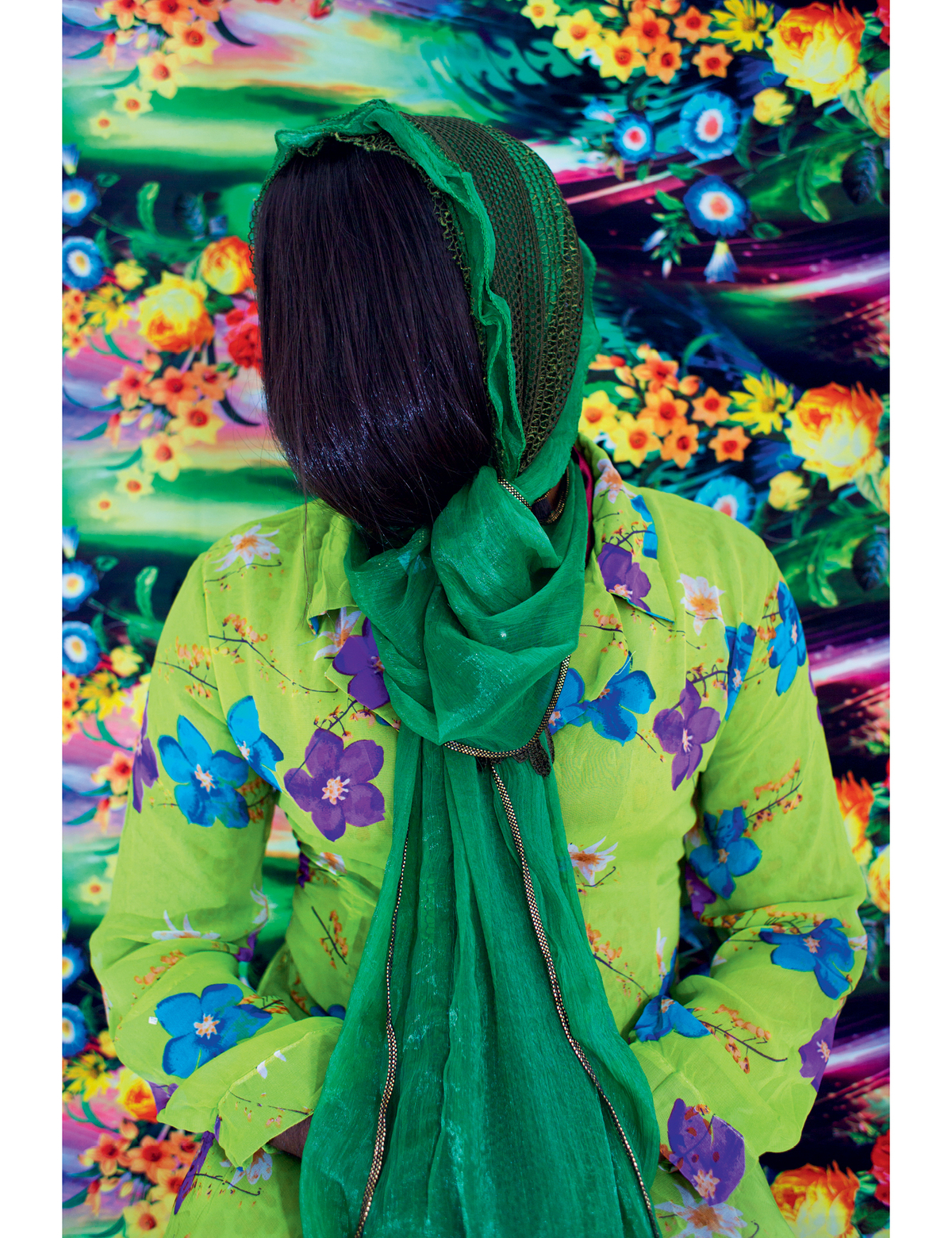

Flora Photographica: The Flower in Contemporary Photography brings the history of flower photography up into the new millennium, which has seen a reblossoming of the art form. Gary Schneider’s radiant black-and-white still lifes, Ann Mandelbaum’s bright but sinister shots, and much more are collected in one big glossy volume. Poignant essays by William A. Ewing and Danaé Panchaud accompany the images. —Elena Clavarino

Elena Clavarino is an Associate Editor for AIR MAIL