“The Henry Mancini of the New Wave”

At some point in the 1980s, a curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art told Duncan Hannah, a thirtyish artist from Minneapolis who’d moved to New York in the early 1970s and had fallen in with the CBGB crowd, that he loved how his paintings “mythologized everything.” At least, that’s how Duncan recorded it in one of his diaries, which he kept for decades and stuffed full of observations, doodles, and clippings.They recorded his hookups, hang-ups, and hangovers, his brushes with fame and infamy, and the books, records, films, exhibitions, and concerts that kept his imagination in a perpetual state of overstimulated fandom.

The fact that Duncan didn’t pass editorial judgment on the curator’s observation suggests that he accepted it with gratitude. After all, mythmaking was not anathema to Duncan; it was at the core of the rock ’n’ roll he loved (the flash, the pow, the primacy of image), of the tales he spun about himself and his army of friends, and of his art.

Duncan, a cherished friend and contributor at AIR MAIL, a painter and a collagist and the author of the acclaimed Twentieth-Century Boy (derived from his 1970s diaries), died of a heart attack at his house in Connecticut last weekend, at 69. Like the man himself, his paintings felt blissfully anachronistic and yet entirely of the moment, chronicling, as they did, the parade of his day-to-day obsessions.

They were dreamy reiterations of the artist’s distracted, even haunted preoccupations—semi-forgotten movie starlets, old speedsters and coupes, classic orange Penguin paperbacks, Ascot-worthy Thoroughbreds, and proud steamships whose giant funnels felt almost like middle fingers raised in the direction of modernity.

At times, Duncan feared that he’d engineered his own obsolescence when he chose to be a figurative painter in the era of conceptualism, Neo-Expressionism, and performance art. The Whitney curator reassured Duncan that the road of art history is long and winding: there would always be twists of fashion, fads, and fate; we can never know how the future will judge what we create.

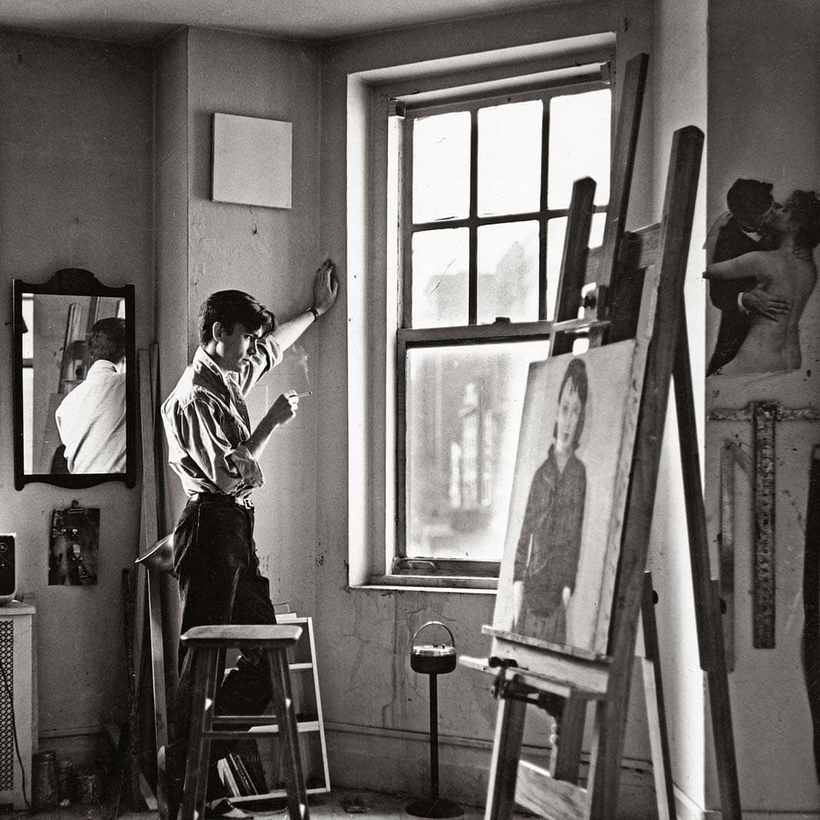

And so, year after year, as the gyres of the art world turned, Duncan stood at his easel every morning (for decades on the Upper West Side and, later, in a townhouse in Brooklyn), applying color and form to canvas, summoning images from deep within—wherever it is that hazy memory and subconscious desire collide with the collected detritus of pop culture.

The haunting and singular tableaux he produced can only be described as Hannah-esque: a short-skirted woman pulling back on a bow and preparing to let an arrow fly; the Beatles’ doomed bassist, Stuart Sutcliffe, posing in his underpants on the cover of a nonexistent magazine called Novela Film; a lone climber in a green sweater gamely mounting an impossibly steep rock face; an untold number of Citroëns or Ferraris in crooked streets or on racecourses that looked oddly familiar and yet somehow alien.

There was also an endless procession of boudoir studies—distillations of an unabashed, even starstruck worship of femininity. At a public talk not long ago, a hand went up and Duncan was asked the inevitable question about the “male gaze.” Duncan, as was his habit, told the truth simply and without apology, saying that, to him, such paintings and drawings were about that most universal of human emotions—love. (Some of these were collected in Studies of the Female Form, which Dashwood Books published in 2019.)

Glenn O’Brien once noted in Artforum that Duncan’s work “causes problems for critics because they can’t figure out if he’s retro- or post-something.” The same could be said of Duncan in person, whose mien was that of a character out of Brideshead Revisited—tweeds, flannels, knit ties, loafers. But there was no program to be historical or anti-modern, no calculated art-world shtick.

You could never forget that here was the guy who had led the official fan club devoted to the epoch-making early punk band Television (as a drummer, he’d auditioned for the group), who partied with Andy Warhol and David Bowie and Lou Reed, and who starred in Amos Poe’s 1976 nouvelle vague–inspired underground movie, Unmade Beds, alongside another eye-catching downtown scene-ster: Blondie’s Debbie Harry.

O’Brien referred to Duncan as the “Henry Mancini of the New Wave, or the power-pop Balthus,” and there was something to that. He became an 80s art star who showed with the bigs, but he found the so-called avant-garde to be vastly conformist, self-important, and grasping. His naturally sunny Midwestern demeanor did not say “tortured artist,” and his much-noted attractiveness—the young Duncan could have passed muster on the cover of Tiger Beat—meant that he was forever in the throes of either capitalizing upon or warding off the inevitable descriptor “cute.”

What darkness there was had to do with the net of alcoholism, which he cast off for good in the fall of 1984. It was life or death. “My benders take the same debauched, chaotic course, and leave me nearly dead,” he confided to his diary that year. “I can lose a whole week. It all unravels. Merely blotto. Stop being an idiotic daredevil.” He stopped. When he died last weekend, he hadn’t taken a drink in almost 38 years.

Everyone who ever encountered Duncan came away affected by his radiant bonhomie, his joie de vivre, and his capacity for endless curiosity and tale-spinning. He was an anecdotalist without equal.

He might mention the time he found himself coming to in a psych ward under the name “Modigliani.” Or how an old girlfriend of his had had a love child with a Rock & Roll Hall of Fame–caliber rock god. Or how Allen Ginsberg was constantly trying to pick him up. Or how he once showed up at Janis Joplin’s dressing room with two buckets of Kentucky Fried Chicken. Or how, during one particularly off-the-rails bender, he kicked off the evening at his Manhattan apartment and woke up 12 hours later in Chicago with no recollection of ever having left town.

Some of these ended up in Twentieth-Century Boy, in which Duncan took in Manhattan’s demimonde like a one-man version of the Goncourt brothers; it widened the circle of his amused and astonished admirers and can be considered an important document of an era.

In one of our last text exchanges before he died, he offered an airy, nonchalant aside about the jazz trumpeter Chet Baker injecting heroin into his own private parts. Pure Duncan. His stories tended to involve human foibles and frailties, often his own. They were never self-important blather. They were told with a grin and an eye twinkle: child-like wonderment at the strange spectacle that is humanity. For Duncan, each day was a pageant.

“I envy painters,” Iris Murdoch once said. “I think they are happy people.” I often had that feeling about the eternally boyish Duncan as I watched him taking daily sustenance from the pleasures of plying his craft, making his friends laugh, or sharing his latest passions. (A recent one was the British band Dry Cleaning.) “I love painting,” he said. “To me, Whistler is cool. Vuillard is really cool. I don’t think, ‘Oh that’s fusty and dead.’ When somebody’s good, nobody betters them.”

Duncan showed us that painting isn’t dead and that, for all the mythologizing about his 70s and 80s exploits, it was always about the work. A couple of his paintings reside in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The ones he never got to finish, we can only wonder about. His dying—suddenly, without warning, well in advance of old age—seemed to many of us to be extremely out of character. And yet he went, at home, with his wife, Megan Wilson, nearby and a French film from 1962, Les Parisiennes, on the TV, which is precisely the kind of movie he might have texted or phoned about, happy, as always, for a new opportunity to share.

Today, a note he’d written fell out of one of his gallery catalogues and landed faceup on the desk, a sign-off as good as any: “Until next time … Duncan.” —Mark Rozzo

Like No One Else

My wife, Lisa, and I were in Miami in early 1997 at the film festival where a movie of mine was being shown. We hadn’t been there together before, and so we walked around the Deco hotels and many art galleries. In one of them we saw a painting of two young boys, 12 or so, looking at a piece of paper, a letter maybe. It was well painted in that the boys looked like boys wearing sneakers, one with the laces undone, on a beach, the distance properly receding.

But there was a message, and not on the piece of paper but from the painter to me.

Time is brief. And memories are what we have.

“Yes,” I thought, “I know that, but why are you telling me this? And who are you anyway?”

“Duncan Hannah,” the gallerist said, pointing at the painting, explaining what I hadn’t asked. We bought the painting.

Then, a few years later, Lisa and I met Duncan and his wife, art director Megan Wilson, and became friends. In New York and California, in Paris (where we shared a gallery), in Vienna, and in upstate New York. He, a fine, elegant, amusing, and amused artist, who in his background had many harum-scarum adventures in a gloriously misspent youth, was now sober.

And then I saw more of his paintings, of people, in a street, a room, outside beside a car, usually of a certain vintage, something to be remembered for its fineness of line. Or sometimes with no people, a street with an old movie theater languishing on the corner.

And also, his small paintings of young actresses from the 1960s, usually nouvelle vague French ones, slim and eager, with their futures ahead of them. Whatever they might be.

People might say Duncan was like, say, Edward Hopper, a painter of marooned people, the lonely.

But Duncan was like no one else. His paintings understood joy and hope and adventures to come. A joie de vivre to be looked for and found.

But still, for me, there was his message.

Time is brief. And memories are what we have.

Lisa and I had dinner with Duncan and Megan and some others on Saturday, June 4, he looking nothing like his 69 years, slim and well turned out on a warm evening, witty and curious and always friendly in his manner. Good company. We parted affectionately that evening as we always did, Lisa, who adored him, giving him an extra hug.

On the following Saturday, only a week later, he had a heart attack, with Megan trying to revive him. But he died, before E.M.T.’s could get him to the hospital.

A dreadful shock to all of us, in many cities and countries, who truly loved him.

Time is brief. And memories are what we have. —Michael Lindsay-Hogg

Mark Rozzo is an Air Mail editor at large and the author of Everybody Thought We Were Crazy: Dennis Hopper, Brooke Hayward, and 1960s Los Angeles

Michael Lindsay-Hogg is working on a memoir about the first production of Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart, which he directed at The Public Theatre. He also had a successful exhibition of his paintings at Max Farago’s Frieze show in Los Angeles.