In 1969, David Bowie launched the most sublime ad campaign in rock ’n’ roll when he timed the release of “Space Oddity”—as in “Ground Control to Major Tom”—to the Apollo 11 launch. Planet Earth was blue and there’s nothing he could do. It is a stunning song, and it transcends the synergy. It is really for anyone who has traveled too far and is exiled forever.

Bowie went there willingly and never looked back. Now pop music is dominated by branding, but it was a new idea at a time when people worshipped the Beatles and looked down on the Monkees. Bowie would soon be beyond the need of a peg for his art. He would be the Man Who Sold the World.

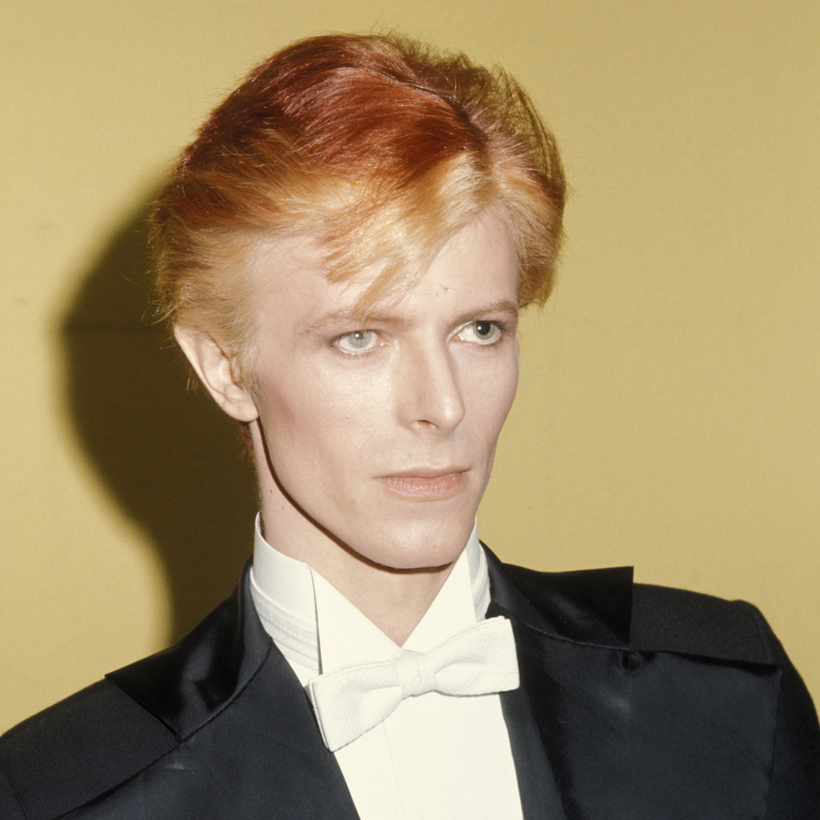

Turn and face the strange, Bowie told us on “Changes.” In 1971, he appeared on the cover of an album in a dress, confident that the world would catch up. Ziggy Stardust had to make way for Young Americans, for Low and “Heroes” and Scary Monsters. Each record was an event, an entirely new creation. Way before MTV, he made music more visual, and, impatient with available sounds, he created new ones.

He left this planet in early 2016, but he never seemed terrestrial while he was here. He called a song “Loving the Alien” and it seemed autobiographical. I was in the same room with him once, and I can attest he was not quite of this world. “Is there life on Mars?” he asked in a glorious song that bears an uncomfortable resemblance to Paul Anka’s “My Way.” At that moment, I felt he’d been beamed in from somewhere.

Bowie left behind a vault, and, on the sixth anniversary of his death, we are being given more access to it. Toy, an album recorded in 2001 and leaked onto the Internet in 2011, is now being given a three-disc (discs, remember discs?) reissue.

In 2001, Bowie was in his mid-50s and hadn’t had a hit since the 80s. After Let’s Dance sold more than 10 million copies, he signed one of the most lucrative deals in the history of the music business and entered a long period of irrelevance. He had become Major Tom in reverse. Every time he tried to relaunch that rocket—as a goblin king among Muppets in Labyrinth, in a forgotten band called Tin Machine, on albums people don’t speak of in polite company—people would flock to his shows as nostalgia gigs and wonder, as they do with many idols, What happened to David Bowie?

He was not going to rest until he found the magic again, and, on Toy, the usually forward-looking Bowie looked back to 60s songs from the pre–“Space Oddity” era, when he was kind of an adorable novelty act. The chords are less startling; the sentiments are more quaint and dated—a time of Swinging London and karma men. Toy could have been called “Twee.” And yet there is pathos hearing Bowie revisit an era before he could get his teeth fixed, when he sang a duet with a laughing gnome.

Compare the 2001 tracks with the 60s originals, and the big difference is feedback. Bowie had been covered by Nirvana and was a fervid advocate of the Pixies, and the album he recorded after Toy included a cover of their song “Cactus.”

On the opening track, the lyrics “Everything’s fine, I dig everything” don’t quite land from a fiftysomething man in the year of 9/11. (“I’ve got more friends than I had out for dinners,” he brags. “Some of them were losers, but the rest of them are winners.” Cheeky.)

Keep listening, and the poignance comes through. On “Let Me Sleep Beside You,” the meaning of the title unfolds:

Place your ragged doll with all the toys and things and deeds

I will show you a game where the winner never wins

The young Bowie knew there would be time to give up childish things; the elder Bowie sings it back to that callow fellow. The title track, “Toy (Your Turn to Drive),” is the newest-sounding track. The lyrics are sparse, and the atmosphere reminds you of the Bowie of Low with the distortion amped up.

When we are 16, we learn a car is not a toy, and responsibility comes as it does. A song, an album, a career, may look like a toy on the outside, but it can bleed for you, too. It can also be mortal. Young Bowie is so broke, in “Hole in the Ground,” he digs everything, even a place to hang his hat. “Shadow Man,” he tells us, is “waiting up ahead.” Or, as he put it later, “time takes a cigarette.”

By the time he exited the universe, 15 years after recording Toy, his estate was said to be worth at least $100 million. He once said that he had a firm handshake from holding on to his money. Listen to the acoustic tracks on the third disc, and Bowie is raw, vulnerable, singing “Karma Man” and “Baby Loves That Way” with the wistfulness of an aging Thin White Duke who wonders what’s next, who has been out of the Zeitgeist for a long time.

Bowie decided to shelve Toy when he began recording tracks for Heathen and realized that he was onto something. His subsequent tour, supporting an album called Reality, would be cut short by a heart attack, and after that, Bowie never performed another full concert.

Two days before Bowie died, of liver cancer in 2016, he released Blackstar, and since his illness had been a closely guarded secret, most of us were gasping with the news and stunned that he’d left with some of the deepest and most powerful work of a life that was not of this earth. This swan song finally lived up to the promise of Ziggy Stardust, larger than life, bigger than death, the biggest spectacle of them all.

It has been six years, and the shock will not wear off. We have been rummaging through his catalogue, looking for new miracles in the work we had been ignoring.

Toy dusts off a mystery, leaving room for others. When Bowie was dying, he finally figured it out. Toy shows us something he decided not to release. By the time he released Blackstar, a birthday present to himself two days before the end, he was sure. He took it all too far, but, boy, could he play guitar.

Toy, by David Bowie, releases in a three-CD deluxe package on January 7

David Yaffe is a professor of humanities at Syracuse University. He is the author, most recently, of Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell