There is something unnerving, distasteful even, about certainty in modern art. We identify with and valorize struggle and the twists of contingency. Francis Bacon likened the act of painting to roulette, and he did so approvingly. Joop Sanders believed “the outstanding thing” about his friend Willem de Kooning was his “equivocat[ion].” Doubt, he might have continued, is what separates the sublime from the mechanical.

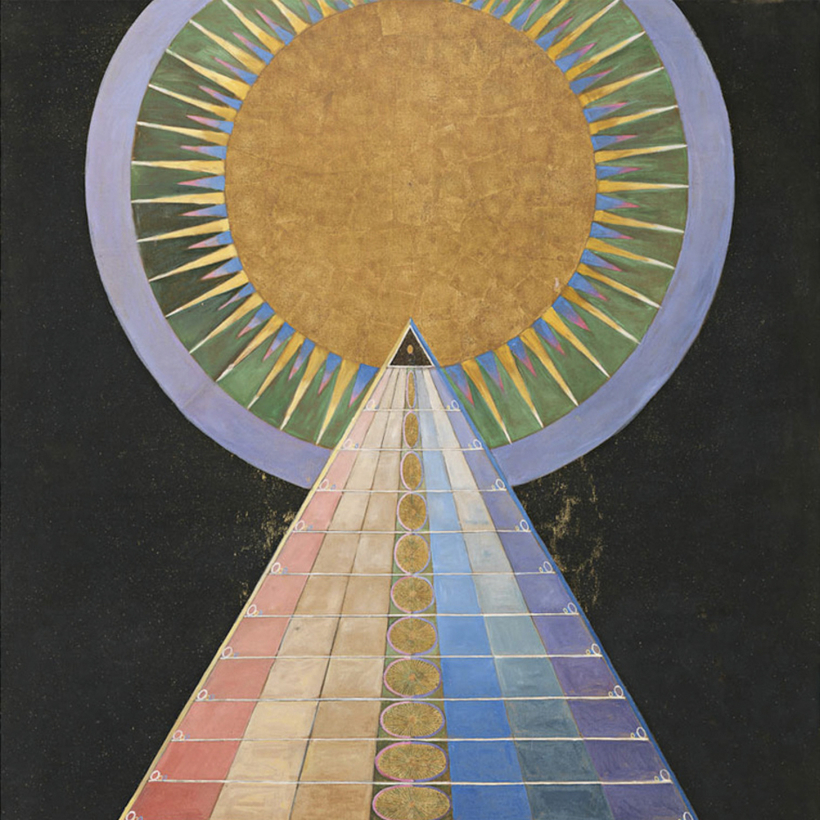

Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) has been ignored for her sex, for her insularity (early-20th-century code for not being active in Paris), for her mysticism—and, somewhat by extension, for her complete and unapologetic want of doubt. Her creations were guided by “higher spiritual beings” (not to be confused with dead people).

A decade ago, MoMA curator Leah Dickerman found “what [af Klint] did absolutely fascinating, but [I] am not even sure she saw her paintings as art works.” In 1987, Hilton Kramer dismissed af Klint’s images as “essentially colored diagrams” unworthy of consideration alongside her abstract peers. That she was expressly averse to offers from the non-anthroposophically inclined to buy and exhibit—an unsurprisingly limiting precept—did not help.

As Julia Voss recounts in Hilma af Klint, her rich and illuminating portrait of the artist, though Wassily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, František Kupka, and Arthur Dove also studied theosophy, none of them “ever publicly suggested that their canvases were the expressions of any consciousness other than their own.”

Theosophists were, besides, not popular at the best of times. “Perhaps I did not like Theosophy, but only Theosophists,” G. K. Chesterton wrote in 1936, when af Klint was still very much alive, “but I did not dislike them because they had erroneous doctrines…. I disliked them because they had shiny pebbly eyes and patient smiles. Their patience mostly consisted of waiting for others to rise to the spiritual plane where they themselves already stood. It is a curious fact, that they never seemed to hope that they might evolve and reach the place where their honest greengrocer already stood.”

Origin Story

She was born, likely at home, in the Military Academy Karlberg, where her father, Victor, served as the director, as his father and grandfather—sailors, all—had before him. If af Klint did not take to her primary schooling (“I can’t remember much more than that school caused me grief”), she did to painting: “Then I started out on the path of art, which made me happier. The task consisted of reproducing. I had no ideas of my own.”

At the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, in Stockholm, she drew from life and began attending spiritual meetings. Around 1888, af Klint executed the only known set piece of her career, Andromeda by the Sea. The accomplished, 52-inch mythological scene, Voss notes, represents Andromeda not in wide-eyed terror but as the “master of her situation.”

She submitted it to the academy for its prize in history painting, which, by only-in-the-19th-century coincidence, went to another, presumably more conventional depiction of Andromeda. Hers received 100 crowns in one of the lesser categories. Offered at auction in Stockholm in 2000 and 2002, it failed to sell, and then realized the equivalent of $3,400.

In 1888, af Klint helped to establish the Swedish branch of the Theosophical Society, and in 1891 first experienced mediumship directly. “[It was] when the painter Valborg Hällström was using a psychograph in her studio and my interest was aroused,” she recalled. “I asked if a few words could be said to me through the instrument. It was said immediately: Go calmly on your way and when I wanted further explanations they continued through life.” She and her circle had little need for Parisian exemplars, Voss relates: “Their travels took them to other dimensions, and for that they needed neither ships nor trains.”

After graduation, af Klint showed regularly in Stockholm. She engaged with Symbolism but otherwise does not appear to have paid attention to contemporaries, at home or abroad. The notes in her archive contain no reference to Munch and evince interest in August Strindberg’s previous incarnations rather than in his work.

Sessions of “the Five,” the closed spiritual group af Klint formed with four women in 1896, produced drawings of spirals, circles, ellipses, grids, diagonals, flowers, leaves, trees, fruits, eyes, vases, and stairs “steered”—with the aid of an ornate, four-wheel planchette—by higher powers.

The 1904 prophecy of one such spirit, “Ananda,” led to her “astral paintings.” The nomenclature came from theosophy—the astral being the subsequent stage beyond the physical—as did the concept of “continual progression” (contrary to Chesterton’s dire evaluation; although her eyes may have been “shiny pebbly”) that prevailed in af Klint’s exclusively serial practice from 1906.

“With a few important exceptions,” Harold Rosenberg once suggested, most avant-garde artists “found their way to their present work by being cut in two. Their type is not a young painter but a re-born one. The man may be over forty, the painter around seven.” Af Klint was 44 when she was reborn and embarked on the, in her words, “groundbreaking” progression of canvases that would define her and “astound humanity.”

Af Klint did not marry, made and fell out with friends in seemingly equal measure, and tended to resist intimacy. Her apartness makes Voss’s subtle evocation all the more impressive. She was slightly more than five feet tall and favored simple dress and habits; on visits to relatives, “Aunt Hilma” slept on the couch. She did nothing by halves—see the 2,058 pages she rattled off between 1917 and 1918 on the “Life of the Soul,” or her 26,000 pages of notebooks—and found comfort in the judgment of the future.

Most distinctive were her categorical disdain for the market and an utterly impersonal relationship with her work. “She was not interested in buyers,” Voss observes. “She wanted an audience of seekers, people who would see her paintings as an alternative.” The spiritual commissioners of “The Ten Largest” (1908), meanwhile, deemed them “paradisaically beautiful” and were recorded by af Klint as concluding: “You’ve now completed such glorious work that you would fall to your knees if you understood it.”

Making sense of her 1,200 abstractions and the nature of her contribution is virtually impossible without consulting her magnificent, seven-volume catalogue raisonné, edited by Daniel Birnbaum and Kurt Almqvist. Af Klint was preoccupied with preserving her output (“as a whole and not mixed with others”) for an appreciative and like-minded posterity. Between her estate—which should be the envy of every artist—biography, and catalogue raisonné, she needn’t have worried.

Max Carter is vice-chairman of 20th- and 21st-century art at Christie’s in New York