How deluded a father can be. In King Lear, the grizzled monarch disowns the daughter who loves him, passing the scepter to her two wicked sisters, who tear the realm to pieces. At the same time, his vassal the Earl of Gloucester drives out his rightful heir and delivers himself to the tender mercies of his second son, born out of wedlock. Paradoxically though understandably, landmark mountings of Shakespeare’s epic tragedy tend to play like concertos, shanghaied by a marquee name firing on all cylinders against an ensemble sculpted in bas-relief.

Chances are that’s what’s in store with the new Lear starring and directed by Kenneth Branagh, set for strictly limited runs at the Wyndham’s Theatre in London’s West End from October 21 and a year hence at the Shed, in New York. In stark contrast, a video filmed live at Stratford, Ontario, in May 2014 plays like a symphony—no vehicle for the One but a densely woven saga of the many, sustained across partly parallel, partly intersecting plots. All is foreground, nothing’s background. It’s tremendous—and also a bracing reality check for those who think of Ontario’s Stratford Festival as the home of Shakespeare in mothballs.

At first glance, the show does raise such suspicions, enacted as it is on a bare Elizabethan thrust stage with players encased in stiff period finery seemingly custom-designed for strutting. But open your ears, and right away you’re receiving a different message. Dialogue from 1606 lands as if written this morning. The speakers know what they’re saying, they understand each other perfectly, and they pose no needless riddles—not even Lear’s half-mad Fool, whose squirrelly riffs scholars festoon in footnotes. There’s no wallowing in fine words, no chanting of the “poetry.” Yet the flood of warring passions sweeps all before it. And that’s not even factoring in the eloquence of the faces, over a dozen sharply individuated living portraits, each deserving of a tribute of its own. Space being tight, we’ll concentrate on the protagonist.

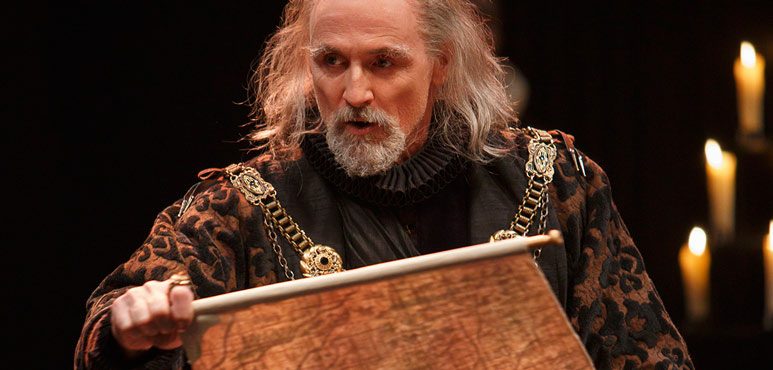

“Come not between the dragon and his wrath,” Lear thunders in the opening scene, conjuring the image of a craggy monster on a mythic scale. That’s not what’s on offer from the wiry, wily Colm Feore, whose screen credits include Pierre Trudeau in the CBC miniseries Trudeau, Glenn Gould in Thirty Two Short Films About Glenn Gould, and the stealthily demonic Andre Linoge in Stephen King’s Storm of the Century. Though his cheek is hollow and his mane is fine-spun silver, Feore enters with a gleam in his eye and a spring in his step, touched with a child’s mercurial innocence. Yet he swerves into the coming tirades with awesome authority, striking chords of heartache as deep as of outrage. “To willful men, the injuries that they themselves procure must be their schoolmasters,” a cruel daughter declares, distilling the action to its worldly-wise moral. Feore reveals Lear’s interior trajectory: the fall, if fall it be, from entitlement to compassion, from presumption to common humanity.

King Lear is available for streaming on the Stratford Festival Web Site, as well as on BroadwayHD and Amazon Prime

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL.He lives in Hawaii