Browsing through the pictures in Book of Mountains & Seas, known to the Chinese as Shan Hai Jing, the “Peach Blossom” poet Tao Qian marveled, “I look up and see the whole universe.” So much for the old saw “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” William Blake, you’ll recall, aspired “to see a World in a Grain of Sand.”

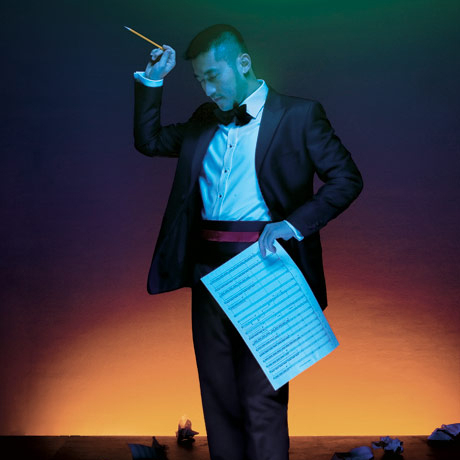

If ever there was an artist born to mediate between supposedly opposing hemispheres, Huang Ruo is the man. A second-generation composer who began his education in his native China but transferred to the United States in his late teens, he fuses high and low influences from alien traditions with bewitching ease. From its premiere in Copenhagen last fall during a lull in the pandemic, his music-theater piece Book of Mountains & Seas now comes to St. Ann’s Warehouse, in Brooklyn. Scored to his own libretto, the adaptation employs a vocal ensemble of 12, two percussionists, and several puppeteers under marching orders from Basil Twist, a designer-director who can conjure living souls from a shred of fabric, a chunk of driftwood, or a tank of water.

On a recent Zoom call, Huang gave us some hints of what to expect.

MATTHEW GUREWITSCH: I’m guessing that Shan Hai Jing isn’t a book so much as a data dump, an attempt to stuff everything there is to know about history and geography and folklore and science into one vast compendium. Does anyone still read it?

HUANG RUO: In China, it’s famous, but most of the people wouldn’t know more than a few stories—out of hundreds! What makes it unique is the way it links everything together: geography, zoology, legends that aren’t just about the earth but also the universe. Mankind is not the main character.

M.G.: So, how do you wrap your mind around all that?

H.R.: For my new opera, I chose four stories which were very close to me when I grew up, stories I felt had a timely, universal meaning that a contemporary audience can relate to. The first story is a creation story, about the legend of Pan Gu, a giant who was born from an egg, and then the egg cracked. We don’t know if Pan Gu is male or female, just that this gigantic being grew to be a million feet tall and supported the top of the eggshell. And that’s how the earth and sky were created.

M.G.: The big bang!

H.R.: That’s right! That’s right! Chaos and creation. When Pan Gu dies, the left eye becomes the sun, the right eye becomes the moon, the blood turns to rivers, and the bone and muscle become mountains. Humans, too, were created from Pan Gu’s body—and they were created last, like in Genesis. We think of ourselves as rulers of the universe, but that’s not the plan. May I also tell you about the fourth story?

M.G.: Please.

H.R.: It’s about another giant, old and honored, called Kuafu. Seeing the sun rise in the East and set in the West, he tried to chase and catch it. And he almost succeeds! But he gets thirsty—so thirsty that he drinks up water from two whole rivers and a lake. And still, he dies of thirst. Dying, he drops his stick, which grows into a forest of cherry blossoms—which, in Chinese tradition, is paradise.

M.G.: What do you make of that story in our time, with the natural world under so many threats?

H.R.: It’s a metaphor for the human ambition to conquer nature. Instead, we consume nature, and everything backfires. But in the story, nature has the last laugh. At first, I thought the ending with the cherry blossoms would be loud and glorious, with the sun bright, hot, and big—but with mankind gone. Then the pandemic came, and I couldn’t write this part. It didn’t relate to what the world was suffering at that moment. When I came back, I changed my mind 180 degrees. I created a very quiet, beautiful apocalypse. The world is still ruined, and everything’s still falling apart. But the fortunate ones who survive dig themselves out and feel the warmth of the sunlight. Not hot—but warm enough, bright enough to feel alive. To me today, that is paradise.

Book of Mountains & Seas is on at St. Ann’s Warehouse, in Brooklyn, from March 15 to 20

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii