This New York City Ballet program, which could be titled “All Austrian,” begins with George Balanchine’s delectable Divertimento No. 15, a buttercream classical confection set to Mozart, who wrote the music in 1777 for a countess in Salzburg. It shares the program with Vienna Waltzes, premiered in 1977 and one of Balanchine’s biggest box-office successes. Don’t let that fool you into taking it lightly. Vienna Waltzes gets deeper with every viewing. As you watch, notice the way the set evolves through the ballet’s five movements: glimmering spring trees eventually lift to expose fin de siècle root-tendrils à la Maxim’s, and then lift further to reveal white root-ball chandeliers in a subterranean ballroom. If you have the eerie feeling that the final movement is taking place in the Underworld, you are not wrong. We experience a descent—moving from the matinee world of Johann Strauss II, to the demi-monde of Franz Lehár, to the death-haunted realm of Richard Strauss’s great waltz from Der Rosenkavalier, in which Balanchine places a lone ballerina on a strange and singular path, one that seems to follow the footsteps of Orpheus in his dark journey (note that she often covers her eyes). Orpheus was very much on Balanchine’s mind when he made Vienna Waltzes. In 1975, he’d choreographed dances for a Chicago production of Gluck’s Orfeo ed Euridice. In 1976, he refigured those dances into the ballet Chaconne. And his use of trees and roots recall the sets for a Gluck Orfeo he unveiled in 1936, at the Metropolitan Opera House. The shadow presence of this myth gives the last movement of Vienna Waltzes its gravity, an undercurrent of mortality that pulls along all five movements. From a distance Vienna Waltzes may read like a survey of the waltz through time—beginning, middle, and end. It actually embodies the human condition in 3/4 time—the eternal round of desire, love, and loss. —Laura Jacobs

Arts Intel Report

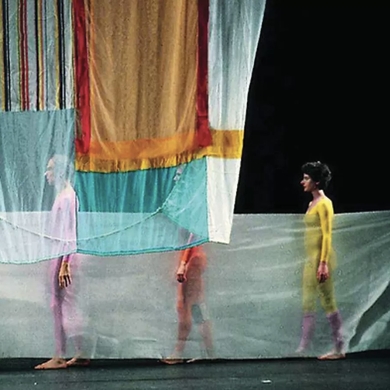

New York City Ballet: Vienna Waltzes

The New York City Ballet in George Balanchine’s Vienna Waltzes.

When

May 8–11, 2025

Where

20 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023, United States

Etc

Photo: © Paul Kolnik