The last few decades have brought us many books on and by the reigning midcentury dancers—Margot Fonteyn, Alicia Markova, Suzanne Farrell, Gelsey Kirkland, and of course, in one book after another, Rudolf Nureyev. But one name has been conspicuously absent.

Those in the know revere this dancer. Those not in the know have never heard of him. And yet, in his day he was held in higher esteem than Nureyev, and was the template for Mikhail Baryshnikov. Unlike them, he never defected. His name was Yuri Soloviev, and in the 1960s and 70s he was the Kirov Ballet’s greatest star. “Cosmic Yuri,” he was called.

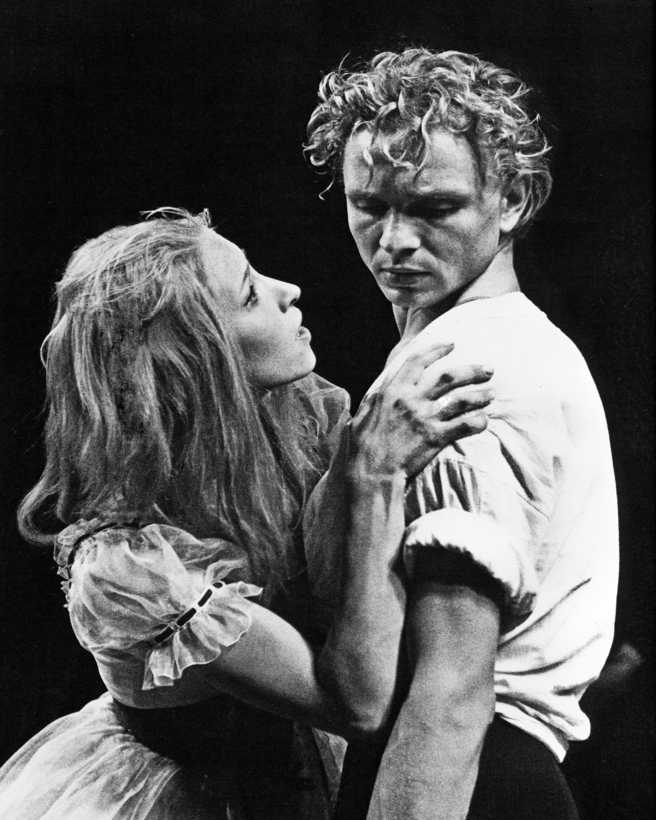

Watch Soloviev on YouTube in The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, The Stone Flower. He is a man before he is a dancer. He is beautifully plumb with the earth, yet is infinitely light in the air. His musculature is sprung—those richly curved muscles in the thighs and calves—and a corolla of blond hair brings radiance to his shepherd’s face. Humility meets majesty. Every move registers.

Where Nureyev was a sexed-up stage predator, Soloviev was angelically poised and generous. Where Baryshnikov was coolly meta-technical, a novel by Nabokov, Soloviev was all heart—Tolstoyan. Until the end that is, when Dostoevsky crept in and the dancer killed himself at the age of 36, in 1977, alone at his dacha in the freezing countryside.

The lost artist now has an eloquent biography—Red Star, White Nights: The Life and Death of Yuri Soloviev—written by the critic Joel Lobenthal, known for his special insight into Russian dancing, and the former non-profit C.E.O. Lisa Whitaker, who as a young woman knew and loved Soloviev.

Lobenthal has been researching Soloviev for many years with an eye to righting a wrong. How can we talk about great male dancing if we don’t know the dancing of Soloviev? But his story is not just about art and aesthetics. It’s about Soviet control and byzantine company politics, about punishing those who don’t defect because of those who did defect.

Soloviev would not play the game and refused to join the communist party. For that, the party crushed his soul. There were those who wanted to help him leave the U.S.S.R., and perhaps he should have left. But he had a wife and daughter there. And he loved Russia, its forests. Watching him dance, you see Russia and its forests.

Red Star, White Nights is deft, swift, deep, and knowing. It is not an opus that exhausts. It is shadowed, of course, by political and poetic dynamics we in the West cannot quite understand. But Lobenthal and Whitaker build a world around their subject—as he grows in artistry and the need for new challenges, it shrinks.

Viewing one of his last performances as the prince in The Sleeping Beauty, taped in Japan just months before his death, the authors write, “Masterful, impeccable in his mature command of technique, the resigned absence in his presence was haunting. A part of him had already gone away. A part remained in a distilled beauty. Spare and dignified, he seemed to silently speak W. H. Auden’s words: ‘Life is a process whereby one is gradually divested of everything that makes it worth living, except the gallantry to go on.’”

Joel Lobenthal and Lisa Whitaker’s Red Star, White Nights: The Life and Death of Yuri Soloviev is out now from Ballet Review Books

Laura Jacobs is AIR MAIL’s Arts Intel Report Editor