The monumental bronzes and marbles of Henry Moore, which see the abstraction of Brancusi joined with the humanism of Florentine masters Brunelleschi and Donatello, are his own form of modernism. Despite making millions in his lifetime (1898–1986), the English sculptor lived frugally and modestly. In 1940, he and his wife left London to live ever after on a farm in Hertfordshire. And in 1951, he turned down a knighthood, fearing the title would “cut [him] off from fellow artists.” Moore rejected art as escapism; he believed abstraction helped viewers grasp a subject’s essence.

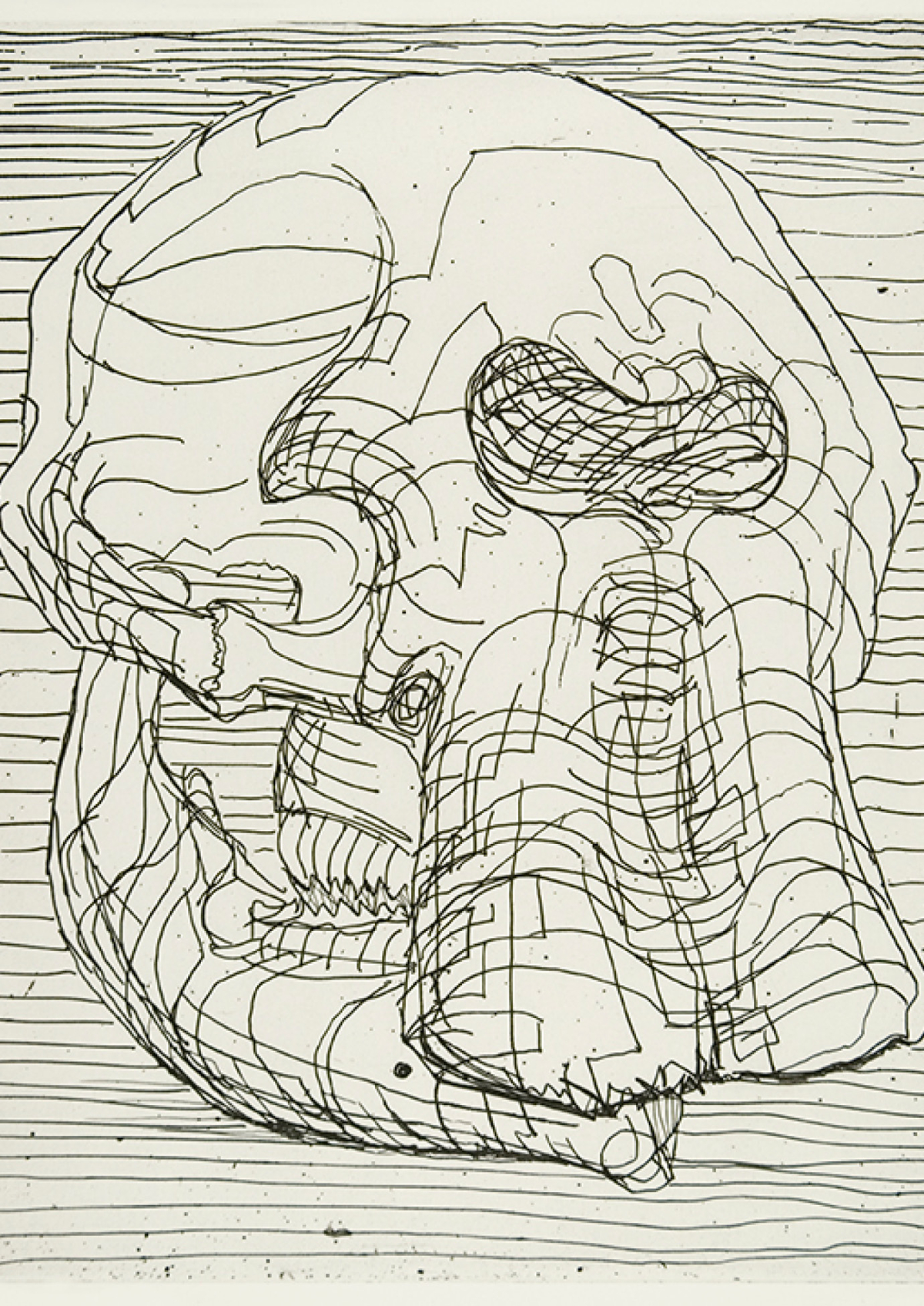

In collaboration with the Henry Moore Foundation, Florence’s Museo Novecento has taken a graphic approach to the artist, pairing Moore’s sculptures and models with 70 of his drawings. While his W.W. II ink-and-pencil images of Londoners during the Blitz are popular, the works on paper that Moore created for pleasure, and those he did for process (it was on the page that Moore developed his ideas for sculpture), have not been made widely available to the public. Subjects of these lesser-known drawings range from natural forms—rocks, roots, animal bones, tree trunks—to the artist’s own hands.

“Henry Moore: The Sculptor’s Drawing” comes almost 50 years after Moore’s 1972 exhibition at the Forte di Belvedere, in Florence, one of the most celebrated exhibitions of the 20th century. The exhibition is accompanied by “Henry Moore in Tuscany,” a smaller show dedicated to Moore’s connection with the Florentine region throughout his lifetime. These also mark the first major Italian exhibitions to open following national coronavirus closures—“a gift,” says Sergio Risalti, artistic director of the museum and co-curator of the exhibition, “to a city that has suffered much in recent months.” —Julia Vitale

Discover

Discover