Producers rarely get much credit, unless they’re bigger-than-life personalities who throw phones, abuse women, or otherwise undistinguish themselves. Ever since Andrew Sarris, the influential movie reviewer for the old Village Voice, imported and elaborated on the “auteur theory” that lionized directors, producers who just produce have been largely ignored. There is no auteur theory for them, nor for writers for that matter. But without producers there would have been dramatically fewer “auteurs,” especially during the 1970s when the studios were aerated by a fresh breeze called the New Hollywood.

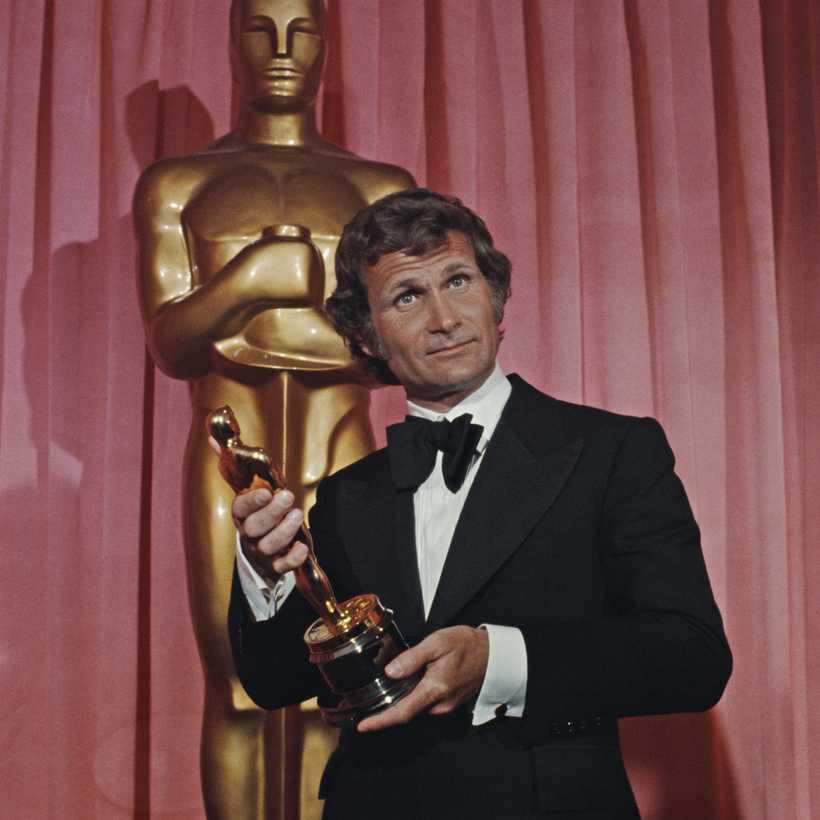

Jerry Hellman was one such producer, arguably the best, and he neatly bookended that era, producing Midnight Cowboy near the beginning, for which he won a best-picture Oscar in 1970, and Coming Home near the end, in 1978. He had a keen eye for the new and different, as well as the boldness and skill to make his way through an industry in turmoil, talking the money into making movies it didn’t want to make.

Think about Midnight Cowboy for a moment. Based on a novel sent him by director John Schlesinger (Darling), it was a homoerotic tale that wasn’t, or maybe was, directed by Schlesinger, a then closeted gay Brit, written by a blacklisted writer, Waldo Salt, and starring nobody’s idea of leading men—a short Jewish character actor named Dustin Hoffman, lucky enough to be starting out in the only era in which someone like him could have become a star, and Jon Voight, a tall, geeky bit player best known for supporting parts on TV. Worse, it was look-away lurid.

Schlesinger recalled having dinner with a studio executive in 1994, and saying, “If I brought you a story about a dishwasher from Texas who goes to New York … meets a crippled consumptive who later pisses in his pants and dies on a bus, would you—’ and he said, ‘I’d show you the door.’”

Indeed, studio after studio turned Hellman down. Jack Warner ordered his guards to shoot him on sight should he come on the lot. But Hellman was canny, knew enough to go to the one company with DNA engineered for the looming cultural revolution that would shake up Hollywood: United Artists, whose head of production, David V. Picker, believed in letting the talent call the shots.

He had a keen eye for the new and different, as well as the boldness and skill to make his way through an industry in turmoil.

Hellman discovered Hoffman in an Off Broadway play called Eh?. “I was bowled over,” he told me when I interviewed him in 2004. He said to himself, “‘Oh, shit, this guy was born to play Ratso Rizzo.’ I’ve often thought it was because we were both short guys with Napoleon complexes.” All well and good, but before production started, The Graduate burst onto the screen making Hoffman a star. He remembered that Mike Nichols, who directed The Graduate, warning him against Ratso: “I made you a star, and you’re going to throw it all away?”

The production was relatively straightforward. It was afterward that the trouble started. Hoffman got a new manager who made fresh demands on his behalf. Hellman toughed it out, and repeatedly refused. “He wanted to meet in a restaurant, but I said I wouldn’t,” he remembered. “I was living in a walk-up on 75th Street in New York, and I wanted to make the fucker walk up the stairs. So he walks four flights, panting and gasping, and asked for a percentage for Dustin. I said Dustin was wonderful, and he got paid more than any of us, but he had nothing to do with the creating this movie, so no, we’re not doing shit.”

Midnight Cowboy became the only X-rated movie ever to win a best-picture Oscar. John Wayne, who won the same year for True Grit, called it “a story about two fags … a perverse movie.”

Cut to six or seven years later when Hellman was prepping Coming Home. It was Midnight Cowboy all over again, another project nobody wanted to make. In 1972, when the film was hatched by Jane Fonda, then being called “Hanoi Jane” for her anti-war activism, and her partner, Bruce Gilbert, Vietnam was a taboo subject. For or against, it was a hot-button issue unlikely to ring the box-office bell.

Midnight Cowboy became the only X-rated movie ever to win a best-picture Oscar. John Wayne, who won the same year for True Grit, called it “a story about two fags … a perverse movie.”

Fonda and Gilbert had lit on the concept of an officer’s wife (Fonda), who has an affair with a paraplegic vet (Jon Voight). As was the case with Midnight Cowboy, the casting was questionable. “Hanoi Jane” had been graylisted and was having trouble getting parts. Ditto Voight. “By the time I hired him for Coming Home, he was dead in the business, box-office poison,” Hellman recalled, adding, Mike Medavoy, Fonda’s agent, told her, “Forget it. This thing wasn’t worth the paper it was written on.”

Hellman and his team did a lot of research with badly injured vets. He recalled, “Everybody high on pot, talking about what it was like to suddenly have to walk around with a piss bag. The thing that these guys could do was cunnilingus … or whatever. Manliness wasn’t necessarily related to a big stiff dick.”

Hellman also wanted Schlesinger to direct, but he turned it down, saying, “Look, I can’t talk to these guys. I don’t know about piss bags and smoking dope. The last thing they need is a baroque British faggot.”

Hellman knew enough about Hollywood to look for gold among the bottom feeders, the discards, whom the powers that be were too blinkered to recognize. Like Hoffman and Voight, Hal Ashby, with the reputation for being a stoner, was one of them. “I’ve worked with directors who could talk the birds out of the trees,” said Hellman. “If bullshit were a great film, they’d be the masters of the universe. Hal was one of the great underrated directors.”

The orally administered love scene between Voight and Fonda was indeed controversial. According to Hellman, Henry Fonda called him and said, “‘Look, I’ve just seen the movie, it’s really disgraceful.’ Now, I knew Henry Fonda fucked everybody who walked. And he was a lousy father, on top of everything. And a very arrogant man, right?” He told him, “‘There’s nothing to talk about. Hal has done an absolutely wonderful job. I’m not going to touch it. Period.’ I never spoke to him again, and he never spoke to me again.”

The result spoke for itself. Coming Home was nominated for eight Oscars in 1979. It won screenplay, two best-acting Oscars for Fonda and Voight, but lost best picture to The Deer Hunter. All told, Hellman only produced seven films, but they were all quality productions. He got 17 nominations, six Oscars.

Hellman was always a fish out of water in Hollywood. He had grown up on New York’s Upper West Side, and said proudly, “I’ve never made a studio picture. My sensibilities aren’t their sensibilities. I didn’t have publicists writing stories about me, and I didn’t want to fuck starlets, and all of that. I’m not one of those guys. I was very serious about what little work I did. And I tried to work with guys who were equally serious. And I think I succeeded in that.” Today, he would be producing for Netflix.

Hellman produced two films after Coming Home: Promises in the Dark, in 1979, and The Mosquito Coast, in 1986. Starring Harrison Ford, Helen Mirren, and River Phoenix, The Mosquito Coast was directed by Peter Weir. In 2001, Hellman got married for the third time, to Elizabeth Empleton, and moved to Great Barrington, Massachusetts, where he spent his final years.

Peter Biskind is a New York–based writer