“Voice! Voice! Voice!” opera’s Old Believers cry, as if the great tutti frutti of art forms ran on just one thing. In truth, general audiences care just as much about window dressing. Birgit Nilsson and Franco Corelli move on, irreplaceable, but do the masses abandon Turandot? Not if you give ’em the old razzle-dazzle, as the Met makes it its business to do. Hence the recent box-office bonanza of a Philip Glass blockbuster that takes three long acts to tell no story about a pharaoh of whom most of the public knows next to nothing.

First performed in Stuttgart in 1984, Akhnaten reached the Met stage in 2019 in a production by Phelim McDermott, who stitches deluxe textiles, costume jewelry, and barrels of bric-à-brac into a glacial, gorgeous ceremonial. Broadcast live that season on November 23, the video quickly rose to the top of the hit parade on the company’s streaming archive—and has stayed there. The title character has yet to sing a note when attendant jugglers lay down their balls and ninepins, unwrap his naked body from the shroud he sleeps in, and encase him in a hieratic, wasp-waisted Robe of State fit for the Virgin Queen. Onstage, sometimes doing nothing at all is the really hard part.

A radical anti-documentary, Akhnaten completes Glass’s “Portrait Trilogy” of operas dedicated to historic disrupters. The driving force behind Einstein On the Beach (1976) is the Theory of Relativity; that of Satyagraha (1981), Gandhi’s idea of nonviolent resistance to injustice. The bee in Akhnaten’s bonnet is the doctrine of a single god—Aten, the sun. Claiming Aten as his father, Akhnaten swept aside Egypt’s ancient pantheon, but the new religion died with him, done in by the priests and the generals. For the purposes of this opera, to know this is to know all. Most of the text is in dead languages, sung without subtitles.

As for the music, even listeners long deaf to the composer’s trance idiom may want finally to open their ears to its considerable fascinations. (The hypnotic visual counterpoint introduced by those jugglers is helpful that way.) The vocal component, be it said, offers few of the customary pleasures of song.

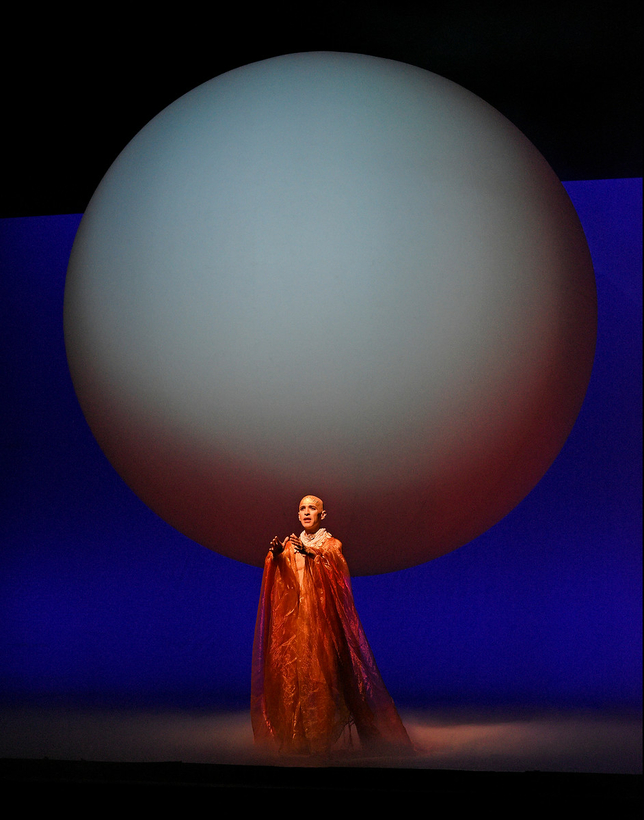

The title role demands a countertenor who at moments of peak exposure can pump out the same pitch over and over, in strict time, at identical volume and intensity—fusillades arguably as taxing in their way as the diamantine runs and roulades of Handel. Face smooth as a Noh mask, his mouth shaped in a giant O, Anthony Roth Costanzo fires each note like a javelin dipped in liquid flame.

As Akhnaten’s mother Queen Tye, Dísella Lárusdóttir pings with bell-like accuracy in a more elevated register. As his sister and wife Nefertiti, the mezzo-soprano J’nai Bridges mirrors Costanzo in long lyrical lines she cannot always quite sustain. Michelangelesque (or shall we say Mosaic?) of stature, the bass Zachary James takes the speaking role of Amenhotep III, Akhnaten’s dead father, holding forth in lofty English that rivets even as it mystifies.

A frequent complaint about Glass’s music is that its repetitive rhythms feel robotic. The same has been said of Vivaldi. Under the baton of Karen Kamensek, the crackerjack Met Orchestra lends the nonstop instrumentals elasticity and a heartbeat in moods from elation to despair. It’s in solo passages, especially for brass and winds, that Glass dispenses his most ravishing melodies.

Akhnaten is available for streaming on the Metropolitan Opera Web site. The latest production will open at the Metropolitan Opera on May 19

Matthew Gurewitsch writes about opera and classical music for AIR MAIL. He lives in Hawaii