That one can still descend into the great, sloppy trough of tumbleweed pageantry that is Exile on Main St. is miraculous. In fact, that we can, at this knotty moment in history, listen to the music of the men who wrote that album 50 years ago tomorrow—ladies and gentlemen, the Rolling Stones—is nothing short of a miracle.

Aside from being the rock ’n’ roll album, it’s the rock ’n’ roll album as: a child of divorce; a double-barreled blast of love and loss; an unadulterated paradox; a beautiful piece of filth; and an enduring monument of what music can mean not just as a supplement to words but as a substitute for them—what we supply when we’re at a loss for speech, or under the weight of a profusion of it.

At the risk of sacrificing the interests of fanatics for those of the uninitiated, here’s some history. It’s 1971, and the Rolling Stones are the most famous band in the world. The only problem is that they’ve just escaped from under the thumb of Allen Klein, their conniving former manager and a thumb himself, at great cost. They are, at least in relative terms, broke.

Adding insult to injury, the Labour government in their home country of England has imposed a 93 percent tax on high earners, so any hope of getting out of financial trouble while residing in the U.K. is lost.

Together with a new financial manager—the shrewd, aristocratically soigné Prince Rupert Loewenstein of Bavaria—the Stones decided to move to the South of France. It was there, on the twinkling, tender shores of the Côte d’Azur, that Keith Richards rented Nellcôte, a Belle Époque villa passed from the banker who built it to a shipping family, to the Nazis, to … well, naturally, Keith Richards.

In the sleepy commune of Villefranche-sur-Mer, the Stones would live out the nominal paradox of their next album: England’s, and the world’s, favorite band, banished from their own country, a sort of twisted Paradise Lost. Each night, on the wrong continent, a British rock band descended into the filthy, warren-like basement of an otherwise palatial home to record intrinsically American music. Which is to say that, that summer, the Stones recorded the greatest rock ’n’ roll album of all time.

Soul Survivors

Nodding to the home’s supposed history as a base for local Gestapo during W.W. II, Richards said in a 2010 interview that recording at Nellcôte was “like trying to make a record in the Führerbunker. It was that sort of feeling.… Upstairs, it was fantastic. Like Versailles. But down there … it was Dante’s Inferno.” Nevertheless, it was the closest approximation of a studio that the house had to offer.

The recording of Exile on Main St. was life lived as a game of musical chairs, with apparently little thought given to what would happen when the music stopped.

Nocturnally, hooked up to their mobile recording studio parked out front, the Stones cobbled together most of the songs in that dank dungeon. (The remainder of the recording and finishing touches were done at Sunset Sound in Los Angeles.)

By day they slept, scored drugs, savored the relative obscurity they found in the creaky, medieval South, and partied with a cast of characters that ranged from William Burroughs and Gram Parsons to Terry Southern, Anita Pallenberg, and Bianca Jagger, whom Mick had married in May of that year.

The band’s hours, and presumably the guest list, were largely legislated by the amber-hued movements of Richards, whose tendency to overindulge in opiates and whiskey left him M.I.A. for long stretches.

On the twinkling, tender shores of the Côte d’Azur, Keith Richards rented Nellcôte, a Belle Époque villa passed from the banker who built it to a shipping family, to the Nazis, to … well, naturally, Keith Richards.

There’s another incongruity, one that betrays the band’s understanding of their genre’s deceptively two-part name.

In the apparently nonchalant mixing of pleasure with work—the wanton sex and partying and a rather loose adherence to office hours—it might seem like the Stones were trying to go all the way till the wheels fell off. Like they were rocking rather than rolling.

But that was only a roguish flourish to distract from a tactical retreat. With the 1967 drug bust at Richards’s English estate, Redlands, the wicked wreck of 1969’s Altamont festival (where Meredith Hunter was killed by Hells Angels while the Rolling Stones performed), guitarist Brian Jones’s hollow-eyed death by drowning in 1969, and England’s austere rebuff behind them, the Stones had to play chess rather than checkers.

By putting on the renegade raiment—wearing the “black hats,” as Richards puts it—that they’d so effortlessly decked themselves in countless times before, they disguised the sensitivity that makes them artists rather than very stylish bums. Instead of taking a break from music, they doubled down on it: Exile on Main St. was an 18-track double LP that demonstrated as much variety as it did quality. Its louche looseness and swindling twang is offset by lyrical honesty—“onstage the band has problems”; “bell bottom blues”; every lyric in “Sweet Virginia”—and gyroscopic melodies that make evasion (exile, if you will) more attractive than lawfulness, fiction more mystically enticing than fact.

Even the critics, who initially hated the album, fell under the occult spell of the Stones and the billboards they had put up on Sunset Boulevard when Exile on Main St. was released, as if to suggest that joining Hollywood in its frontier hucksterism was akin to beating it.

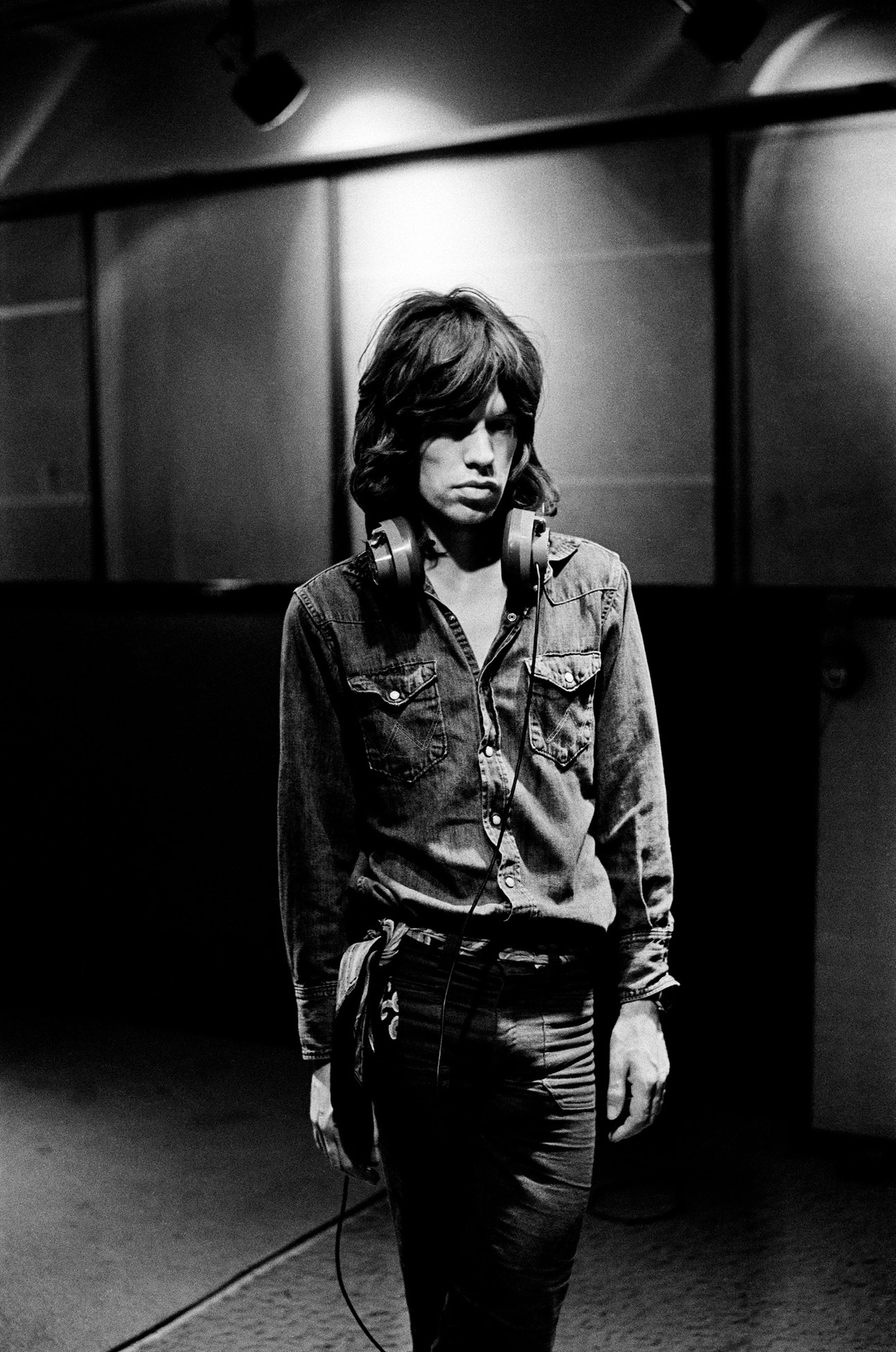

Less than a month after Exile on Main St.’s release, the Stones would kick off a 48-show tour that was worthy of the album. In addition to being one of the most successful concert runs ever, it was among the more gloriously documented. Though Truman Capote notoriously failed to complete his reporting assignment for Rolling Stone amidst a bout of post–In Cold Blood writer’s block, photographer Jim Marshall did not.

His collected photos and proof sheets of the tour have been compiled in the form of an anniversary edition of his book The Rolling Stones 1972, and feel remarkably fresh even if the speedball of dissoluteness and good fortune documented therein would become clichéd in the hands of subsequent, more affected rock groups. Before that summer, if any band had thought about throwing televisions out of hotel-room windows, they hadn’t done it on film before—and especially not in a documentary with the title Cocksucker Blues.

And yet we’re 50 years on from all that, and what the album and, yes, those old white men embody seems lost under the cellulite that’s accumulated on the humorless haunches of a culture that was once so limber and free. Though the freak-show sensibility manifested in Robert Frank’s contact-sheet-style album cover for Exile on Main St. can be found routinely on display today, the artistry of exploring what unites us all has been supplanted by what could more fairly be called “the artistry of nothing.” We’re living in a time of publish and perish, when inaction—or the most antiseptic, generic action—is the advisable route.

The importance, then, of this great monument of rock ’n’ roll—which by 100 will either be “Ozymandias” or Old Testament (one can hope)—is not in the music. Or not just in the music. There’s already more than enough of that to go around.

No, Exile on Main St.’s value now lies in the profligate circumstances of its own creation: the indulgent symbolism of dice tumbling, wine being passed, and bandmates being searched for but not lost. It’s about the hoisting of a flag, not the waving of one; it’s about retreat, but not surrender; it’s about plundering the soul and passing the loot on. And it’s about the begetting of a single question from 18 answers: Who’s on Main St.?

Nathan King is a Deputy Editor for AIR MAIL