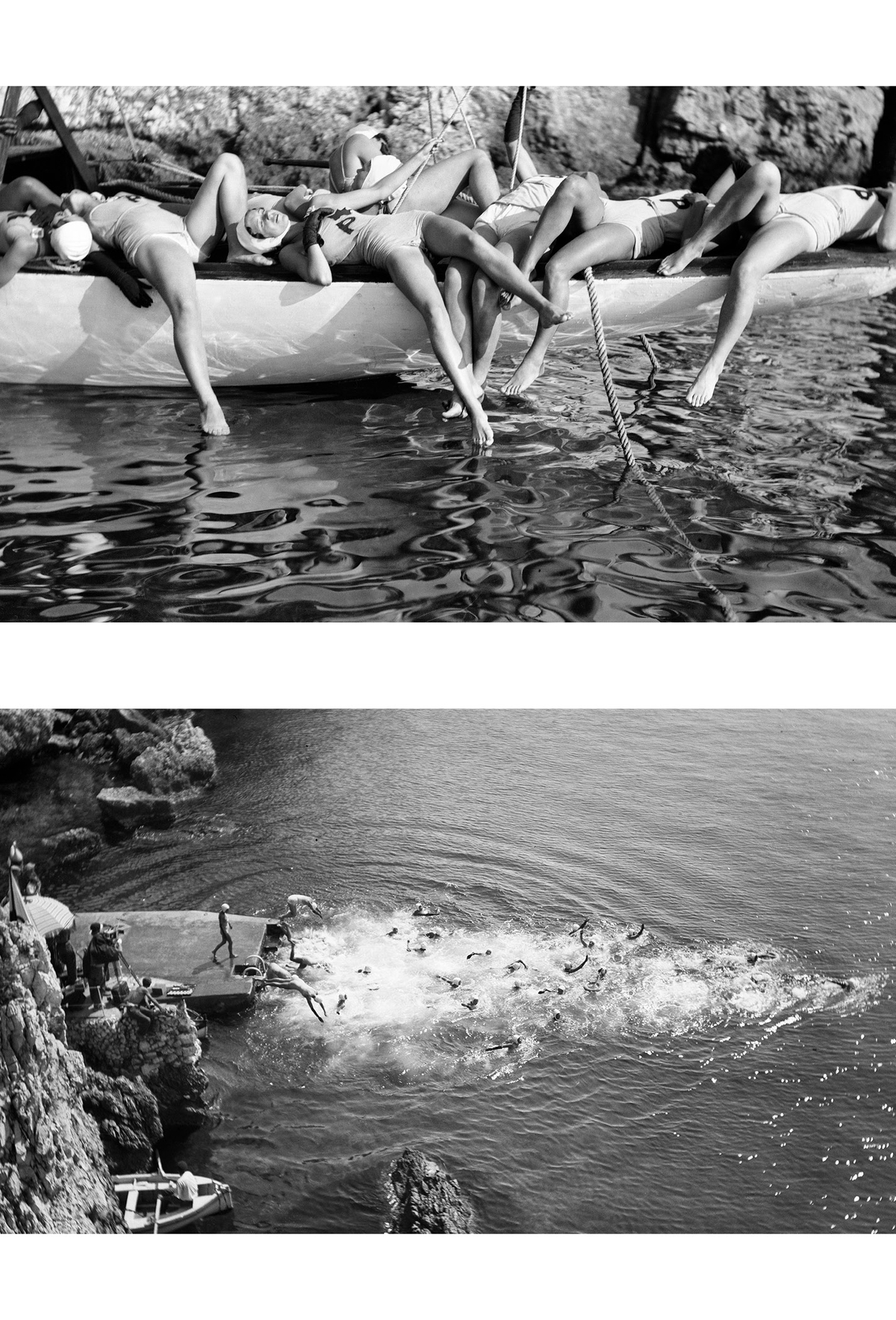

Jacques-Henri Lartigue’s voluptuously tactile 1932 photo of a welter of heat-struck young women recumbent on the bow of a tiny boat over the Mediterranean hits viewers as a culminating vision of the South of France. In a configuration both posed and haphazard, four sets of open legs emerge from pale bathing suits, and end in dangling toes licked by salt water. You have to look closely to see that there are in fact six women—one is turned away, another upstaged by all the busy open legs. There are no faces at all.

At first glance, men will see the girls as naked, and the woke will be appalled. It’s a surprising photo in the canon of Jacques-Henri Lartigue, whose photographs are always, always deeply personal.

Born in 1894 with radar set for joy, beauty, and happiness, Lartigue was given a camera for his eighth birthday and never stopped taking pictures of his family, friends, girlfriends, and wives until his death at 92, in 1986. The only mistress he never dared photograph was Marlene Dietrich.

He was sensitive to temperature, to sights, to nature, to smells, to perfumes, and to music—putting on a record of Debussy for the young Edith Piaf, who sat, intimidated and mute, at a small dinner he’d organized for her before her Monte Carlo debut, in 1942. He kept himself in shape with daily gymnastics, took boxing lessons, danced in boîtes all night long. Attracted by any combination of naïveté and what he called “perversity,” he loved young women. “Each pleasure,” he wrote in his diary, “is in proportion to the faculties you have to receive it.”

Born rich enough to disdain money, Lartigue became a painter. When the family money ran out in the late 20s, he continued his socialite-playboy life in the South of France, racing along, by preference naked, in his open-top American Willys-Knight roadster with no windshield between Cap-d’Ail, Monte Carlo, Nice, Antibes, and St. Tropez.

The hotels—the Martinez, the Carlton—gave him exhibitions, as did the Cannes casino. Lartigue couldn’t always pay for his canvases, his ideas, or his rooms, but each time was saved by luck and last-minute commissions.

Born with radar set for joy, beauty, and happiness, Lartigue never stopped taking pictures of his family, friends, girlfriends, and wives.

A compulsive pickup artist, he declined opportunities only when newly in love, and once dodged a threesome by hiding in a movie house. In 1930, Lartigue spent two years in love, “on holiday” in the South of France, with a model from Romania who’d named herself Renée Perle.

He highlighted what about her was sleek, was lacquered, and from that smooth simplicity created a style that endures today. His luminous photos of Renée are masterpieces that combine the personal, the sensual, and the stylish. Most remarkable is the one where Renée, a wave over her left eye, a ton of bracelets climbing up her forearm, rests her long fingers over one low-slung, bra-less breast under a ribbed undershirt.

The photos were first widely seen 40 years later in his 1970 book, Diary of a Century, and had such an influence on fashion that Yves Saint Laurent made the white trousers in this photo the center of his 1972 Rive Gauche summer collection, and all the cool kids around Karl Lagerfeld wanted to dress as if it were 1932.

Renée’s hundreds of tiny bracelets, her waved hair, painted lips, and immensely long, pointed, lacquered nails set a template for Lartigue’s preferences. Renée and he broke up at the beginning of 1932. He wrote in his diary that his love for her was “a splendid and unbearable illness that could only be resolved by early death” or “accepting to be one of those anonymous little old couples who long ago gave up their purpose and their ambitions, for love.”

He was 38, too old to be so hurt, too young to die. Heartbroken, he fled Paris, but, like a playboy, to ski in Megève.

On the Job

On his return, Lartigue took on the first—and only—salaried job of his entire life, on a movie about to be shot in the South of France. He would be the go-between for a Russian producer and the man who owned the rights to one of the slightly pornographic novels of Pierre Louÿs.

The hero of The Adventures of King Pausole has 366 wives, one for every day of the year, leap years included, and trouble arrives when his daughter hits puberty. The director was another Russian, Alexis Granowsky, a spendthrift with big ambitions for the film and zero interest in women. Between 150 and 180 “queens” were needed for King Pausole.

It fell to Lartigue to do the heavy work of choosing the “queens,” a job the heartbroken playboy took on with appetite, despite a certain apprehension about which old flames might arrive among the flood of socialites, kept women, and actresses who lined up to try out for the film. If any one of them was especially pretty, Lartigue told the director, then he invited her to dinner.

Lartigue raced along, by preference naked, in his open-top American Willys-Knight roadster with no windshield, between Cap-d’Ail, Monte Carlo, Nice, Antibes, and St. Tropez.

Lartigue had better taste than Granowsky, who rejected his best choices, the beginners Danielle Darrieux, who was to star in Children of Paradise, and Simone Simon, who would become known as “the tender savage” of French movies.

Lartigue headed down to the South of France to line up the locations, the women, the wild animals, the extras, the houses (the Château de la Garoupe, Villa Alexandrine, La Leopolda). “My eyes are sated with marble colonnades, sumptuous staircases prettied up with cypresses, fragrant gardens,” he wrote in his diary in July of 1932. “Is this true beauty, or is all this magnificence simply the reflection of the bad taste that grips human beings as soon as they are too spoiled?”

On endless errands for Granowsky, Lartigue drove up and down the Moyenne Corniche in his Willys-Knight, most often in his briefs. The company was paying for the gasoline.

The film began to shoot. One hundred and twenty “queens” arrived, put up two to a room, each one needing to be made up, cooled down, and dressed in the costumes by the society artist Marcel Vertès, whose tapered nymphs can still be seen on the walls of New York’s Café Carlyle and Paris’s La Méditerranée. Lartigue calculated that 120 “queens” meant 12 women per heterosexual man on the film. He had more than his share.

It was August in the South of France—high season for all the social activity that had always been part of Lartigue’s life. Now he had galas and parties as well as his work, and would choose the first girl he saw to be his gala date.

Lartigue stepped back from being assistant director to simply being the photographer. He posed any number of the beautiful “queens” in the gowns by Vertès, arranged in the gardens whose beauty was beginning to nauseate him. The heat was intense—one day the air seemed to pass through an opal. “The hot wind carried shades of transparent mahogany smoke into the sky. The sun more and more hidden behind a strange curtain distorting the colors,” he wrote in his diary. “It’s as if the heat showed us its true, and slightly hellish, color.”

“Is this true beauty, or is all this magnificence no more than the reflection of the bad taste that grips human beings as soon as they are too spoiled?”

The excesses made Lartigue dizzy; now he began to see the 120 “queens” as a herd of sheep transformed into grasshoppers. He couldn’t bear one more drive along the Moyenne Corniche.

The location moved to Eden Roc at Cap d’Antibes, the Comte de Beaumont’s white palace, with, he notes in his diary, “monkeys, pink flamingoes, 103 undressed ‘queens’, a sea-plane, two yachts.”

Lartigue knew he was taking the photos more for himself than to fulfill his duty as “photographer.” He gloated that not even a billionaire could assemble as many beautiful women as the ones he called his pretty camarades, in 60 rooms of this luxurious hotel of the Côte d’Azur. This is probably when he took the photograph of the welter of undifferentiated women floating on the bow of a tiny boat, toes grazing the water.

He’d had too much of it all. The production office dragged out paying him back for the gasoline he’d used on all those trips along the Moyenne Corniche. He quit. It was mid-August, the film nowhere near finished.

Jacques-Henri Lartigue never mentioned The Adventures of King Pausole again. He was done.

But he was not done with the South of France. His second wife, Coco Paolucci, was the daughter of the head of personnel and chief electrician of the Cannes casino, and when that marriage was over, he found true love with Florette Orméa, who came from a part of Monte Carlo called Beausoleil. Though she was 27 years his junior, they remained happily married and bought a house on a square in Opio, less than 15 miles inland from Cannes.

The Adventures of King Pausole barely figures in the annals of cinema, but Lartigue became a legend. “It wasn’t that I had to work,” he wrote in his diary in 1935. “I had to want to have fun.”

Joan Juliet Buck is a writer and actress and the former editor of French Vogue