In 1935, in the preface to the second edition of his book Ancient Times: A History of the Early World, James Henry Breasted wrote, “The discovery of the tomb of Tutenkhamon by Howard Carter has proved to be an epoch-making disclosure of the beauty and refinement of civilization under the Egyptian Empire, and has perhaps done more to interest a large public in the story of the human past than any other single discovery in the history of archaeological research.”

If anyone had the authority to make such a sweeping statement, it was Breasted. Born in 1865 in Rockford, Illinois, spurred on early by Austen Henry Layard’s drawings of ancient Assyrian ruins (proof that the Old Testament was rooted in reality), Breasted received a master’s in Hebrew from Yale in 1892 (so that he could study ancient Biblical cities), headed to the University of Berlin where in 1894 he earned a doctorate in Egyptology (the first American to do so), and then robed in knowledge took a command post at the University of Chicago, where as first chair of Egyptology and Oriental History he fathered the field of ancient history in America. This is the man who forever relocated the origins of western civilization—WESTERN CIVILIZATION!!!—from white Europe (ancient Greece and Rome) to the scythe of land he named the Fertile Crescent, a territory that followed the upper Nile northward to curve east and southeast along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. In other words, the Near and Middle East. Think about it.

But Tut. He was a boy king who died at 18, entombed with artifacts 5,000 strong, a golden hoard of high karat. Tutankhamun exhibitions have traveled four times through the world since the stunning first one, launched in 1961. The most recent tour—the fifth—is also the last. Once construction of the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo is finished, the Tutankhamun argosy will reside there permanently, never to leave Egypt again. This current exhibition, “Tutankhamun: Treasures of the Golden Pharaoh,” just left Paris, where it had a record attendance of 1.4 million visitors. It is now in London at the Saatchi Gallery, until May 3, 2020, and will then spend six months in Sydney, Australia, followed by trips to Japan, Canada, and South Korea.

This is the man who forever relocated the origins of western civilization from white Europe to the scythe of land he named the Fertile Crescent.

Breasted would no doubt be thrilled by Tutankhamun’s charisma and continuing crowds. But the 2003 looting of “Baghdad” (fond shorthand for the The Iraq Museum), and the more recent destruction, by ISIS, of the ancient cities of Nimrud and Palmyra—knives to the breast of every archaeologist in the world. As we learned from the magnificent exhibition at the British Museum last winter, “I Am Ashurbanipal: King of the World, King of Assyria,” scholars are only now beginning to understand these empires and their achievements. (Assyrian palace art is currently on view at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles and comes to the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg, Russia, on December 10).

In Boston, at the Museum of Fine Arts, “Ancient Nubia Now” is up until January 20, and puts the spotlight on 400 pieces of Nubian jewelry, including 140 jewels worn by Nubian queens. The MFA is home to the largest collection of Nubian art outside of Khartoum. Why? Because of the excavations carried out by the Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition in the early 20th century. “Last Supper in Pompeii,” at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology in Oxford, England, looks at the last day of life in the doomed city, when citizens were busy preparing lunch. Did you know that dormouse, fattened on acorns and chestnuts, was a Roman delicacy?

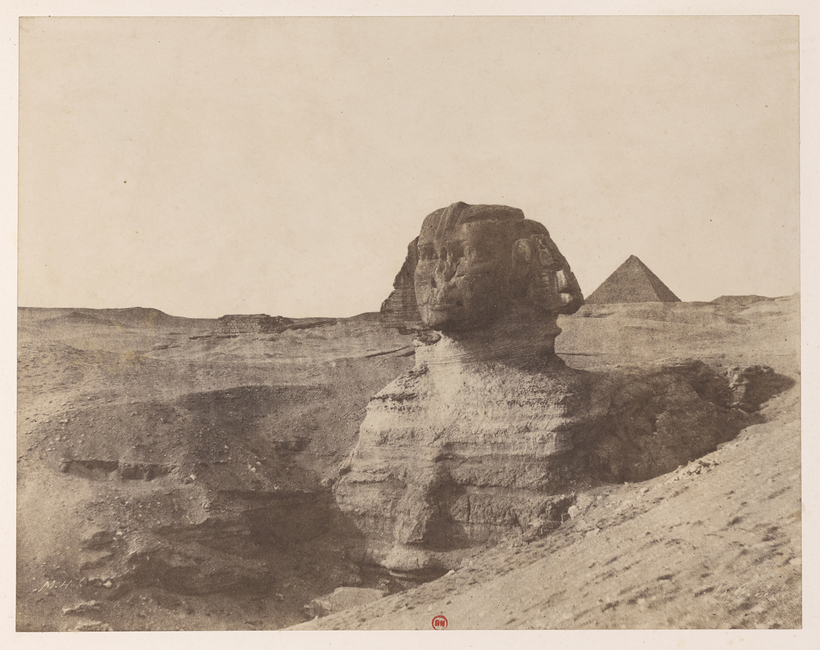

Back in Chicago, the Oriental Institute—a revered museum founded in 1919 by none other than Breasted—is now 100. In September it began its centennial celebration by asking acclaimed contemporary artists Mohamed Hafez, Ann Hamilton, and Michael Rakowitz to create works that speak to ancient artifacts in the collection. At the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, ”Signs and Wonders: The Photographs of John Beasley Greene” is running through January 5 (the exhibition then travels to the Art Institute of Chicago). Greene died at age 24, in 1856, but in his short life he took ghostly photographs of ancient Egyptian art and architecture. This is the very first exhibition of his pioneering work. And in England the Royal Shakespeare Company, at Stratford-upon-Avon, has just premiered Hannah Khalil’s A Museum in Baghdad, a play it co-commissioned with the Royal Lyceum Theatre Edinburgh. Two different time periods exist onstage simultaneously—the 1926 creation of The Iraq Museum and its 2006 reopening after the looting. The archaeologist who saw to the founding of “Baghdad” was British. Her name was Gertrude Bell. She and Breasted, similarly formidable, met in 1920, in Aqar Quf, in what was then called Mesopotamia but is now Iraq. Small world.