This year of global crises and massive upheaval is also the year for official solutions to infamous unsolved crimes. In June alone, Portuguese authorities named a viable suspect in the 2007 disappearance of four-year-old Madeline McCann, and the Swedish government shocked its citizens by closing the books on the 1986 assassination of Prime Minister Olof Palme, announcing Stig Engstrom, a graphic designer who died by suicide in 2000, as the culprit. Now a new book by the journalist Ravi Somaiya probes an even older mystery: was the plane crash that killed U.N. secretary-general Dag Hammarskjöld in September 1961 a result of pilot error, or something more like murder? And if it was murder, who had it in for Hammarskjöld?

As The Golden Thread, Somaiya’s first book, examines in painstaking detail, foul play is a far likelier conclusion than tragic accident. It is, as Somaiya writes in his author’s note, “a story with so many twists, and so many duplicitous characters, that unraveling it drove me nearly to madness.”

Die-Hard Democratist

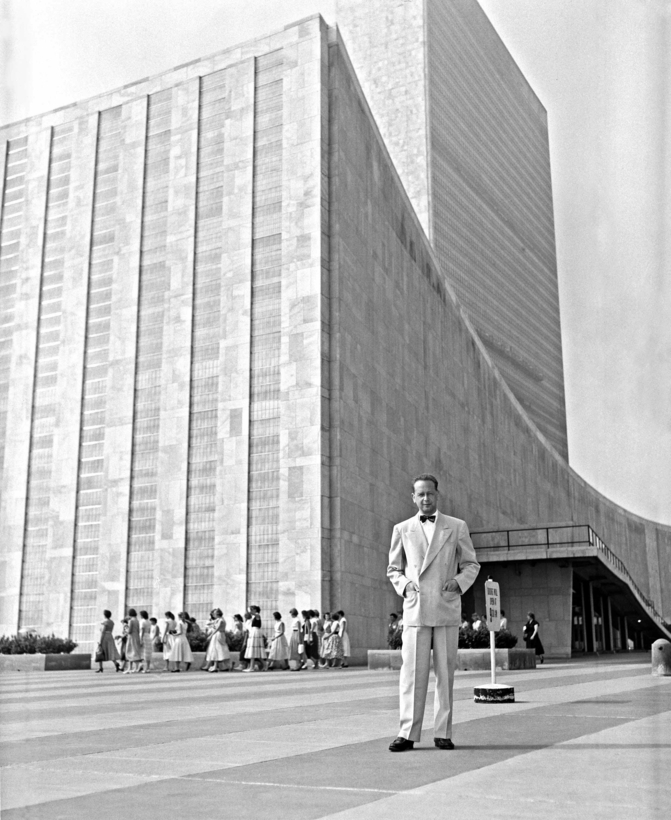

The United Nations appointed Dag Hammarskjöld as its second secretary-general in 1953. He was viewed as a safe choice, easily swayed, depending on which superpower was asking. But they misjudged his quiet implacability as weakness, rather than righteousness. Hammarskjöld had principles, and they centered around democracy, specifically regarding the newly formed Democratic Republic of the Congo, which declared independence from Belgium in 1960. Following the province of Katanga’s secession from the Congo, the country’s democratically elected prime minister, Patrice Lumumba, requested the U.N.’s assistance to stabilize democracy within the country.

Hammarskjöld’s support for the republic angered the superpowers. “The Belgians, the Brits and the Americans saw [Lumumba] as a dangerously left-leaning firebrand.” Lumumba ended up assassinated in early 1961. And several months later, on his way to a peace summit, Hammarskjöld’s plane, the Albertina, crashed in then-Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, shortly before four A.M. on September 17, 1961.

Questions about the plane crash began almost immediately, and in surprising quarters. “Mr. Hammarskjöld was on the point of getting something done when they killed him,” said former U.S. President Harry S. Truman, unprompted, while delivering a speech at his presidential library. “Notice that I said ‘when they killed him.’” Assembled journalists naturally followed up, but Truman would say nothing more. Two official inquiries concluded the crash was an accident, owing to pilot error. Hammarskjöld was awarded a posthumous Nobel Peace Prize within months of his death.

Was the plane crash a result of pilot error, or something more like murder?

Perhaps President Truman’s speculations would have been forgotten entirely. But they were not, because the official story, as Somaiya details, simply did not add up. Witnesses indicated the presence of another plane in the vicinity of the fatal flight, as well as increased activity in the moments before the crash. One observer, who later died in the hospital, said that the plane “blew up” but this was attributed to the throes of delusion. Doubt spurred the likes of George Ivan Smith, the U.N. press representative, Irish diplomat Conor Cruise O’Brien, and later, Swedish investigator Bengt Rösiö and British academic Susan Williams, to dig into the official conclusions and dismantle them. What they discovered, independently and consecutively, is that the Albertina crash was no accident, and that it was far more likely to have been shot down.

Somaiya is not only thorough in his investigation and assembly of the evidence, he also writes extraordinarily well. His style is concise, conveying layers of detail with utmost brevity. (“The Congo is shaped like a real human heart, messy and organic and the size of Western Europe.”) The pacing is also excellent, considering the complexity of the story. He cuts through the tangled weeds of redacted reports and missing documents to produce a coherent and damning narrative, evaporating any notion that what happened to the plane was mere accident.

That said, The Golden Thread raises more questions than it offers answers. That is the mark of excellent investigative journalism, where neat solutions are rare and should be viewed with the appropriate suspicion. Somaiya affirms, and rightfully credits, earlier documentaries and investigations, but also goes further, with his own comprehensive theory of what might have happened to the Congo-bound plane.

What emerges from this book is how the seemingly anodyne Hammarskjöld, who valued peace and neutrality above all, was seen as a mortal threat, because democracy and autonomy in the Congo was also seen as a threat. It will take much more investigation, document declassification in multiple countries, and a strong will to arrive at the indisputable truth of what happened to Dag Hammarskjöld and the Albertina. That we are closer than before is because of the exemplary efforts on display in The Golden Thread, which Somaiya has promised is not his last word on the matter.

Sarah Weinman is the author of The Real Lolita and editor of the upcoming Unspeakable Acts: True Tales of Crime, Murder, Deceit & Obsession