If brevity is the soul of wit, then my friend George Booth wasn’t one.

George, who died this month after a good long run, was a humorist. There is a distinction. Nowadays we lump everything laughable under the banner of humor. Back in Victorian times they were keen to distinguish the two. Humor was genuine and arose from character. Wit was artificial, a kind of verbal sleight of hand practiced by the aristocratic educated elite. Humor was in the pub. Wit in the coffee house. Humor was warm and welcoming. Wit was cold and could cut you up.

You get the picture, but let’s throw some nuance on it by someone well qualified to do it.

The wit makes fun of other persons; the satirist makes fun of the world; the humorist makes fun of himself, but in so doing, he identifies himself with people—that is, people everywhere, not for the purpose of taking them apart, but simply revealing their true nature. —James Thurber

Thurber’s and Booth’s paths never crossed. Thurber died in 1961, and Booth didn’t get published in The New Yorker until 1969. But Thurber certainly would have recognized a fellow humorist. Someone whose humor didn’t punch up or down but elbowed gently to the side.

He would have liked Booth’s dogs too. And I can vouch for the reverse.

It’s fun to imagine a metaverse where Thurber’s and Booth’s dogs meet up. It could do wonders for both.

Thurber’s phlegmatic pooch could have had a calming influence on Booth’s frenetic hound.

And Booth’s could have got Thurber’s off its lazy ass.

So, Zuck, please burn a billion on this.

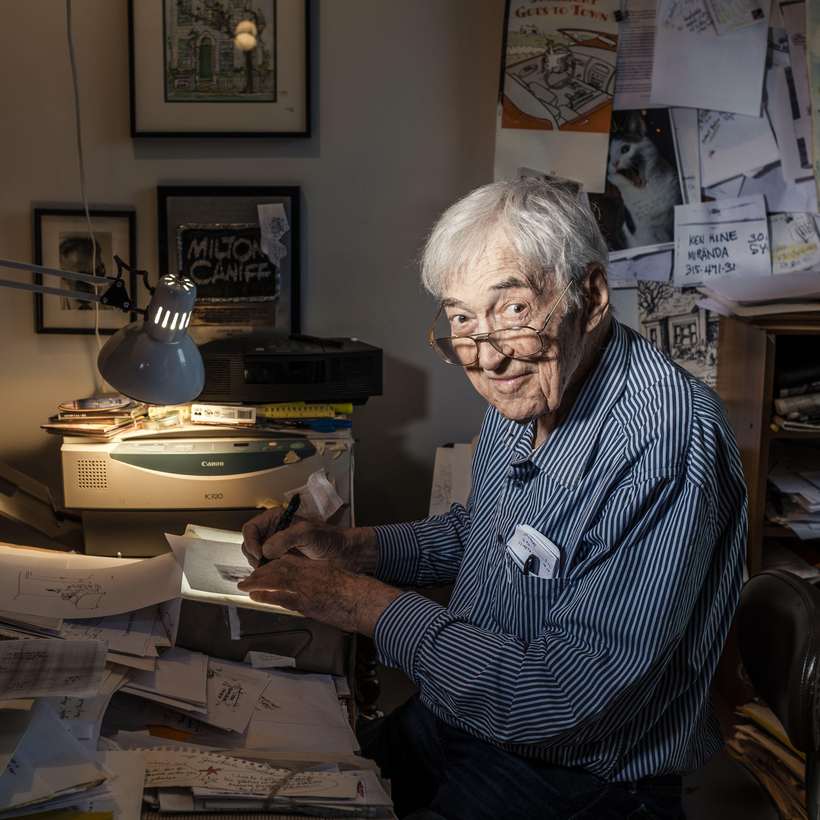

I’m grateful Booth’s world and mine did overlap for exactly so many years. I first met George in the late 70s when I began getting published in The New Yorker on a regular basis.

That got me invited up to the inner sanctum at 25 West 43rd Street to show my cartoons, along with other cartoonists, including George, to the cartoon editor back then, Lee Lorenz.

By that point, George had published well over 200 cartoons and was firmly ensconced in the unofficial pantheon along with such greats as Peter Arno, William Steig, Saul Steinberg, and Charles Addams.

Unofficial though it is, you don’t get thus ensconced “merely” by doing great cartoons, though that is the kind of “merely” well worth aspiring to. You must go beyond that and create a distinct, diverse, and substantial comic world in which those cartoons live, and which enables us to see our world through your eyes, so an English bull terrier is forever a “Booth dog.”

Given his status, it would have been easy to have been in awe of George. He would have none of that. His kindness, warmth, and generosity ruled it out. And even though his loose and energetic drawing style was the antithesis of my cramped pointillism, he sweetly blurbed a book of mine saying I was “the only cartoonist in the whole world who carefully places one raisin next to the other until he has achieved a full-blown situation. I enjoy his raisins and stuff.” Sweet and a little bit goofy. That unself-conscious goofiness was one of the things that made George, living legend that he was, so approachable. Another was that he often approached you.

George was fun. You would think this could be said of many cartoonists because their work, when it works, makes people happy. But, for reasons I know all too well, drawing funny for money can make you glum. George was a glum buster for me and for the generations of cartoonists that followed me. An inspiration as much in his person as in his work. After he died, cartoonists’ encomiums to him were everywhere online.

George had an infectious laugh that infected no one more than himself. Often you weren’t quite sure why he was laughing, or at what, although you knew, given his good nature, it was never at you. The reveal eventually came to me in this cartoon from 1993, which also lets me revel in a particular aspect of Booth’s comic genius.

Nothing may be funny to that cave creature, but everything in that cartoon is funny in a distinctly Boothian way. Not for Booth to go to cartoon central casting for a caveman or woman or the evolutionary forerunner of his iconic hound in the foreground.

It’s been said that comedians don’t say funny things—they say things funny. I’m not sure about that, but I’m sure with the appropriate tweak that fits George’s cartoons to a misshapen T.

Look at the perfectly misshapen Harrington in this cartoon and try not to smile. Now move your eyes around to everything else in the image. By the time you get to those sparse blades of grass they’ll be good for a giggle, too.

We don’t tend to linger over cartoons. We glance at the image and then look to the caption for the payoff, which doesn’t get any funnier the longer you look. Except, for example, here, where the more you look at that self-contented huge lump of a pachyderm, seen from behind, daintily napping, the more you laugh.

You don’t “get” Booth cartoons—they get you. If they don’t, go read Oscar Wilde.

The cartoon below, done in 1974, poses the question that is on everyone’s mind today.

An army of wits and satirists is quick to give answers. I think George would tell them to stand down.

Bob Mankoff is the Cartoon Editor for Air Mail and the author of How About Never—Is Never Good For You?: My Life in Cartoons. He was the cartoon editor for The New Yorker from 1997 to 2017