“I am an old man. When you are this age, you cannot ask young girls to undress for you,” confessed Paul Cézanne when asked about the models for the 200 or so paintings now known as The Bathers.

And so the nudes for those paintings, which consumed the last decade of his career before he died in 1906 at age 67, came from his imagination. This admission may have pained him; Cézanne was known as an especially immersive artist, fixated on shape, form, and real sensation—the master Impressionist. Picasso called him “the father of us all.”

But the Bathers series doesn’t suffer for it; it only marked a new phase in his style. The full scope of Cézanne’s career will be on full display from October 5 to March 12, 2023, at the Tate’s once-in-a-generation show “The EY Exhibition: Cézanne.” From early studies of homegrown apples to later portraits of his gardener, each work represents Cézanne at his finest.

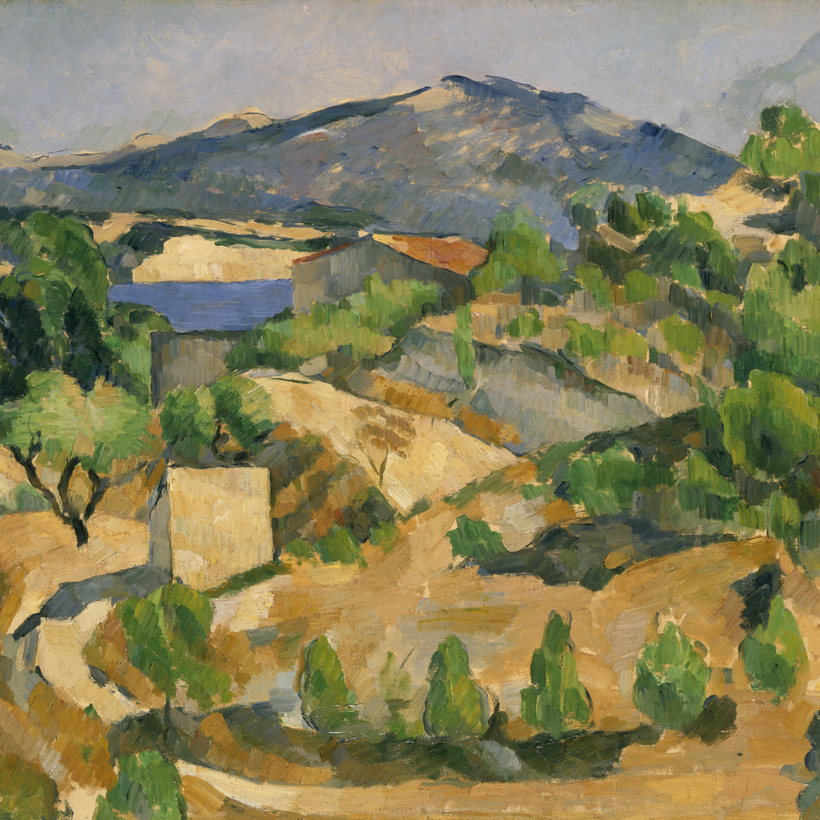

Born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839, he was infatuated with the ravishing, distinctively lit landscapes surrounding him, such as the sunshine on a terra-cotta roof or the skin of a fallen fruit. When you’re face-to-face with a Cézanne painting, the sensation is akin to stepping inside it.

And because these simple yet captivating Provençal scenes still exist today—the same craggy mountains, tree-lined boulevards, and shimmering bays—the Cézanne experience can be replicated by travelers, at least in part.

Picasso called him “the father of us all.”

Autumn is an ideal time to visit Provence. The lavender- and sunflower-chasing crowds have gone, but it’s still warm enough to drink rosé on a sun-dappled terrace. Nearly 150 years ago, Cézanne understood this, too. After settling in Paris, in 1861, he became an ardent patron of France’s growing rail network, and would regularly return to his native Côte d’Azur during the off-season.

Local produce—eggplant, apples, peaches, pears, and figs—figured prominently in Cézanne’s work, so the first order of business is to revisit the region’s street markets, where hydrangeas the size of pom-poms burst from boxes and trays of garlic are piled high.

For its scale and spectacle alone, the Aix-en-Provence market will likely be a highlight. It occurs on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays from eight a.m. to one p.m. in the town center. Saint-Rémy-de-Provence’s market, which occupies Place Jules Pélissier, near the center of town, on Wednesdays, is an ideal spot to pick up Marseille soap, linen tablecloths, and woven baskets.

Antiques seekers will not want to miss the Sunday market in the center of L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue, which draws well-stocked vendors from all over the world. When a restorative pastis is in order, return to Aix and find a streetside table at any bar on the Cours Mirabeau. Cézanne used to frequent Les Deux Garçons, at No. 53, with his friend Émile Zola, although it is currently undergoing restoration.

Cézanne also loved to paint the Bay of Marseille, as seen from the village of L’Estaque, just west of the city. (The light in Marseille inspired not only Cézanne but also Renoir and Fauvists such as Georges Braque, André Derain, and Raoul Dufy.)

Start at one of the waterfront kiosks selling chichis fregis, delicately delicious fried doughnuts flavored with orange-blossom water. Then it’s a short meander to L’Estaque pier, where the Chemin des Peintres (Route of the Painters) begins, a signposted circuit of points that most moved the artists. Take in the view of rooftops, hanging laundry, and the Bay of Marseille at Place François Maleterre, the hilltop church square where Cézanne once kept a house.

With another doughnut for the road, it’s back to Aix-en-Provence, where Cézanne’s paintbrush can be retraced at every turn. Start at his studio at Les Lauves and climb the old wooden stairs to see his paint-spattered smock, as well as the green olive jar that he painted 22 times and the human skulls he captured so memorably in Three Skulls on a Patterned Carpet.

Mystifyingly, nobody at the atelier will mention that another 15-minute walk up the hill is all that’s required to reach Terrain des Peintres (Field of the Painters), Cézanne’s vantage point for painting a Mont Sainte-Victoire. This became his best-known landscape; he was finishing work on the painting when he was caught in a storm in 1906, dying days later of pneumonia.

Next up is the Musée Granet in Aix, home to its own Cézanne gallery. One piece, Nature Morte: Sucreir, Poires et Tasse Bleue, is on loan to the Tate, but an embarrassment of riches remains, including a small-scale oil of the view from Jas de Bouffan, the estate where Cézanne grew up.

Make time for the exquisite Hôtel de Caumont, a majestic 18th-century mansion converted into a gallery, gardens, and restaurant. One exhibition includes a 25-minute film dramatization of Cézanne’s life made with the help of his great-grandson. It’s fairly hammed up, but fascinating all the same.

If there is any doubt that Cézanne is having a moment, it will likely be extinguished in November, when the late Paul Allen’s art collection will be auctioned off at Christie’s in New York. La Montagne Sainte-Victoire, which Cézanne completed in 1890, is expected to sell for more than $100 million. It really puts that Air France ticket to Nice in perspective.

Katie Bowman is the editor for Family Traveller, a contributor to The Times of London and The Sunday Times, and the editor of Amazing Places: 200 Extraordinary Destinations