In 1765, in Paris, a gentleman named Monsieur Boulanger opened a shop that sold bouillon, or concentrated stocks, intended to improve health. An inscription in the shop window read, “Come to me all who suffer from pain of the stomach and I will restore you.” Because Boulanger was ambitious, he eventually offered more than bouillons. When he first served leg of lamb in white sauce, the public’s response was favorable.

Come the French Revolution, chefs were liberated from their posts in aristocratic kitchens. Early bouillon shops such as Monsieur Boulanger’s flourished and even evolved into fine-dining spots. White tablecloths, silver cutlery, and centerpieces were part of the look of these new establishments.

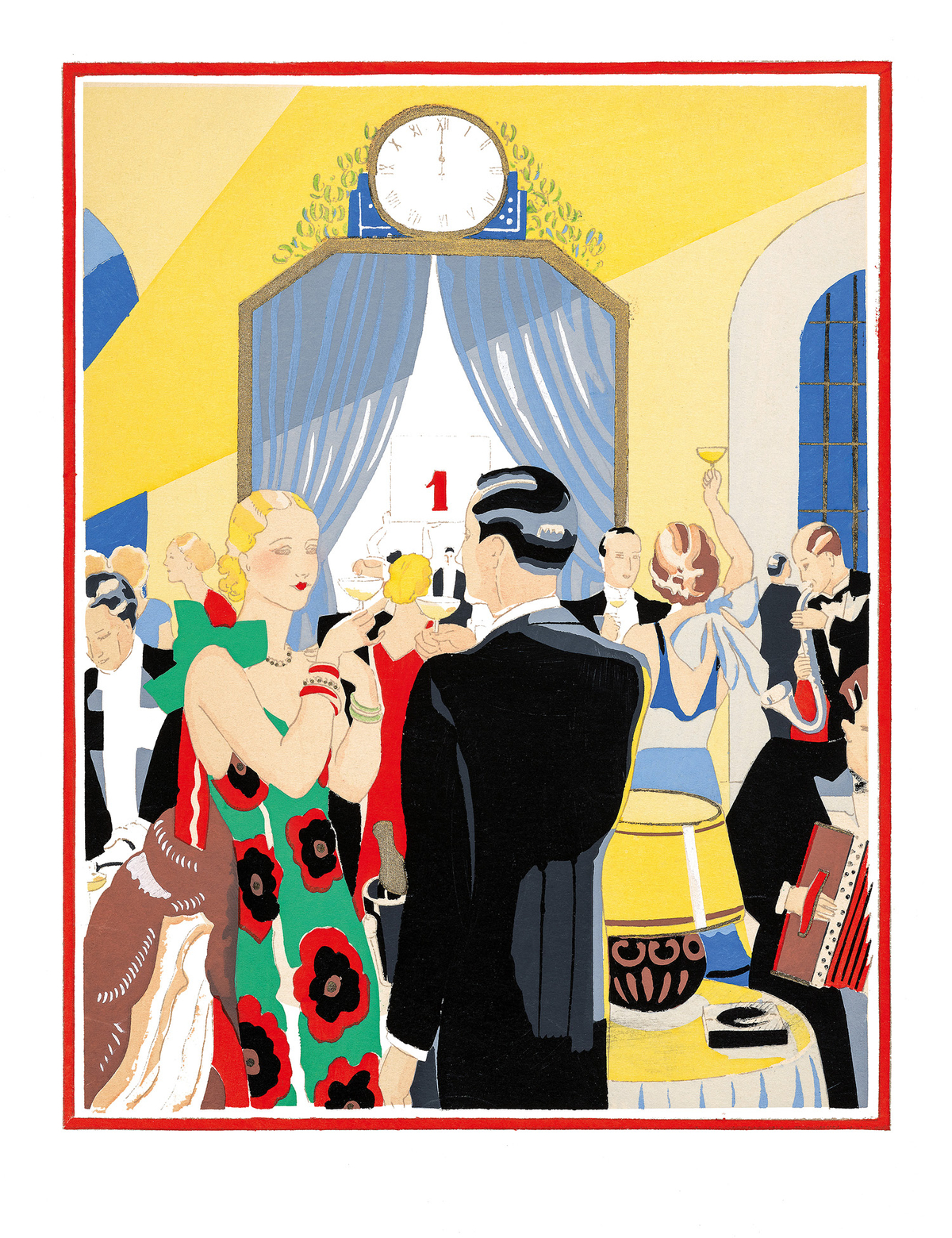

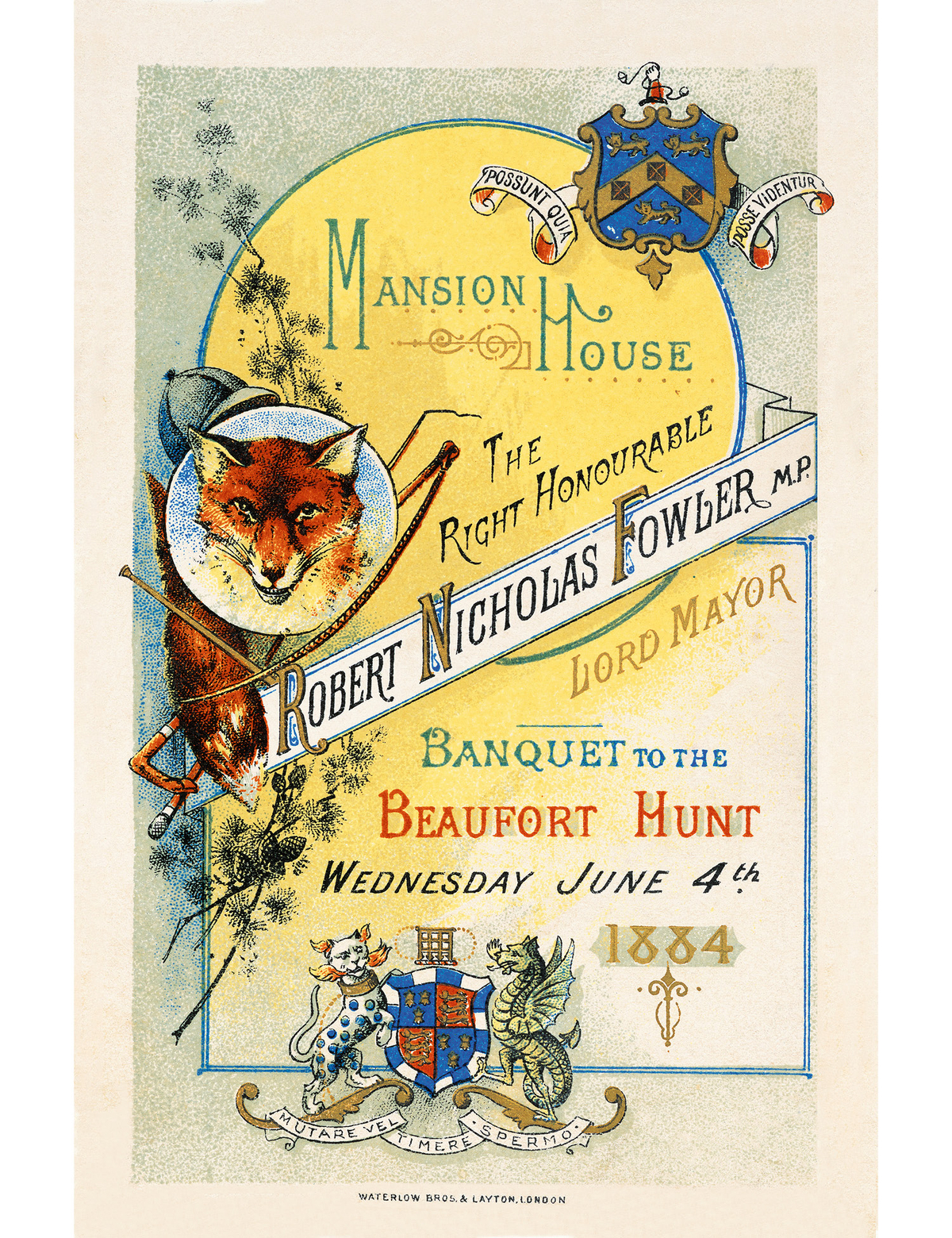

Along with tableware, menus were soon essential to the restaurant experience. By the mid–19th century, simple signboards were replaced by elaborate cartes du jour. Some were informal, with listings on double-sided paper, while others were thicker and more beautifully designed. Train travel increased, and on ocean liners such as those operated by the chic Red Star or White Star lines, the menus from the grand first-class dining rooms became keepsakes. Travelers also held on to menus from elegant wagons-lits and other sleeper trains.

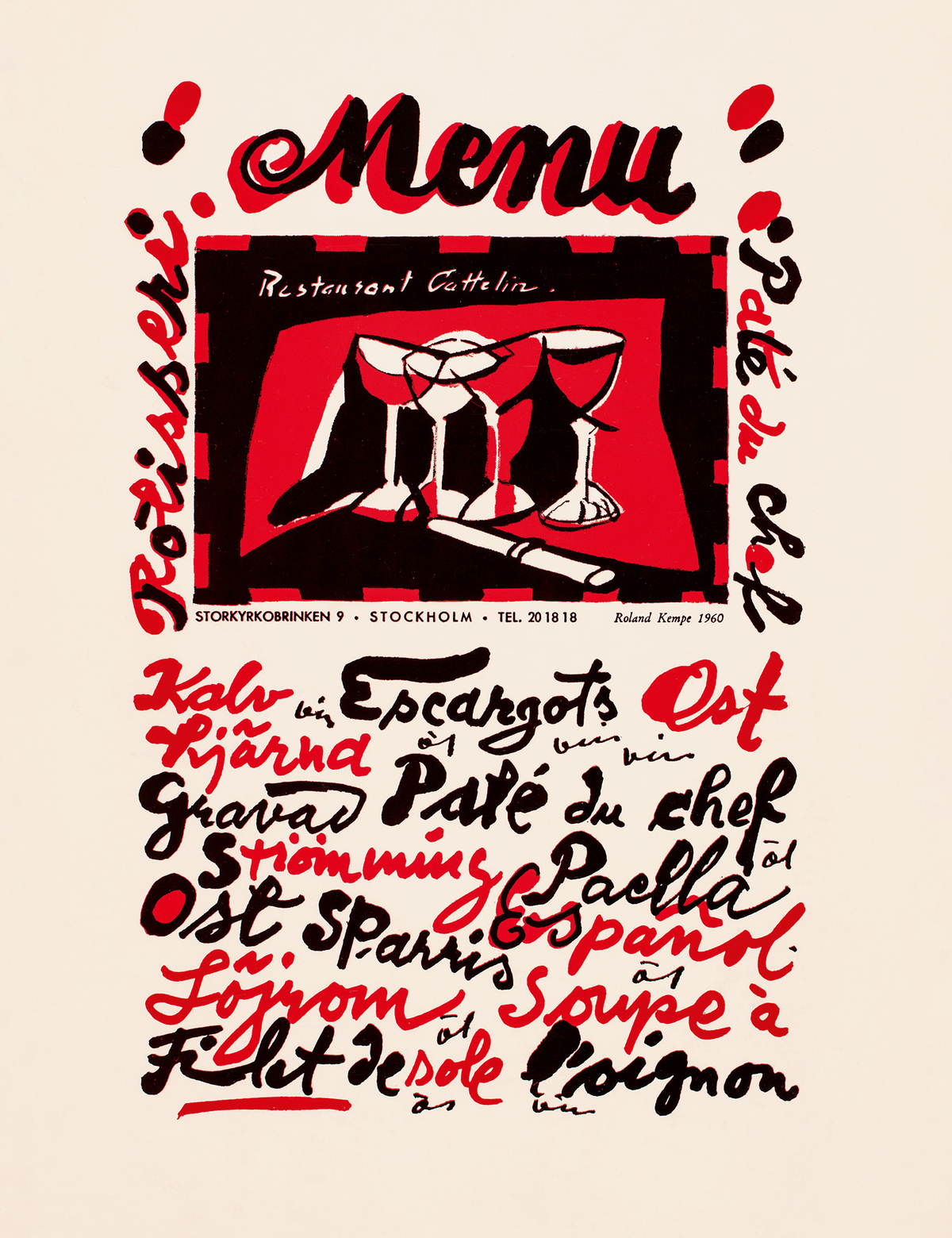

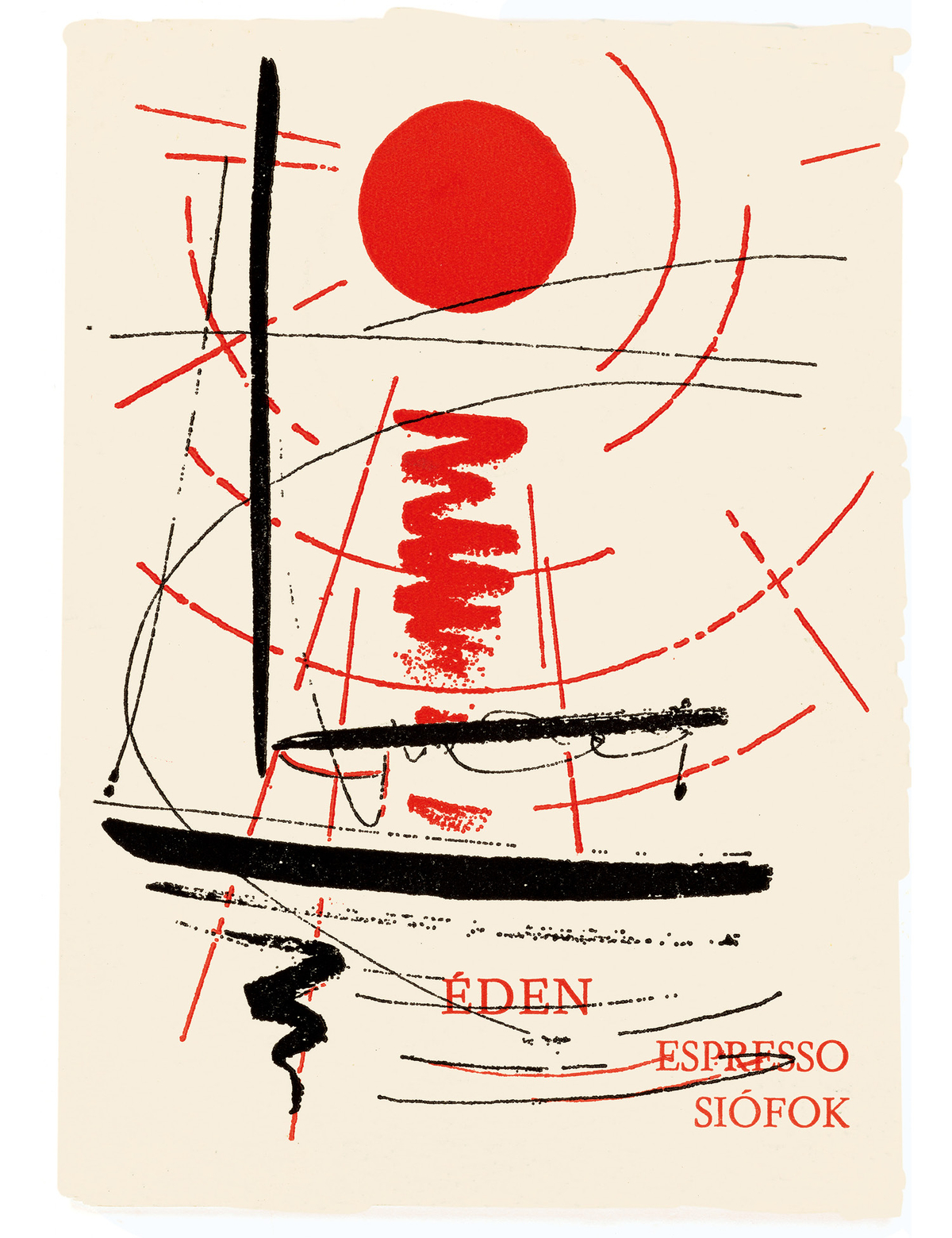

Enter the 20th century, when the Bauhaus, Art Deco, and Moderne schools proliferated. Increasingly, menu covers were blank slates for creativity, and began to incorporate photographs and digital graphics.

Now that the coronavirus has popularized QR codes, the menu—a cultural mainstay—is slowly disappearing. In Menu Design in Europe: A Visual and Culinary History of Graphic Styles and Design, 1800–2000, a poetic new book edited by Jim Heimann, the history of menus is embodied in some of Europe’s most elegant designs.

Highlights include an exquisite color menu for Quinzi and Gabrieli, a hand-lettered carte for Restaurant Cattelin in Stockholm, and the fun, collage-like handout for Club 31, in Madrid. —Elena Clavarino

Elena Clavarino is an Associate Editor for AIR MAIL