I swore off difficult men after writing Robert Mapplethorpe’s biography. When my book was published 25 years ago, it elicited violent criticism from some of his friends. They felt I’d been too hard on the controversial photographer whose S&M pictures had created a firestorm in the early 90s. One bombarded me with profanities. Another threatened to kill me. My publisher wondered if I should hire an armed guard.

When an editor floated the idea of a novel about Beethoven, my first thought was, “Another difficult man.” My second thought: “At least all his friends are dead.”

Beethoven was petty, paranoid, and had a volcanic temper. His various lodgings were filthy and chaotic. Pieces of Verona salami and red herring vied for space with the scribbled sketches of great symphonies. He hired and fired a succession of housekeepers and cooks, claiming they were trying to steal or poison him. His colorful vocabulary consisted of such putdowns as “arch-swine,” “arch-villain,” and “troglodyte.” In one of his ugliest episodes, he engaged in a protracted court battle to wrest his nephew Karl away from his “immoral” sister-in-law. Karl, buckling under the pressure, attempted suicide.

It’s Complicated

My book is narrated by Countess Julie Guicciardi, the dedicatee of the “Moonlight” Sonata and the “dear, enchanting girl” he fell in love with in 1801. In a letter to a friend, he confessed that she loved him too and that for the first time his thoughts had turned to marriage. When I first began writing I worried that I wouldn’t be able to access Julie’s emotions. There were times when he was so impossible that I wanted to slap her across the face and shout, “Snap out of it!”

But then I began to fall in love with him. My heart broke for the small boy whose alcoholic father would pull him out of bed at night to practice piano. I agonized when he confronted the reality of his hearing loss, knowing that it would end his dazzling performing career. I cheered him on through various re-writes of Fidelio, because he had the audacity to create such a valiant female heroine. I laughed at his stupid puns, ignored his awkward attempts at dancing, and suffered through his numerous love affairs with women he could never have. They were usually married or, like Julie, above him in station. He claimed that all he wanted was a pretty face to sigh at his compositions, but I knew that wasn’t true.

Beethoven was petty, paranoid, and had a volcanic temper. But I began to fall in love with him.

He lived completely in his music, and, for a time, so did I. I admired the powerful Eroica and the Ninth Symphony, but the Beethoven I loved was to be found in quieter moments—the “Moonlight’s” plaintive first movement, the sublime Cavatina and Heiliger Dankgesang from his late string quartets.

The Cavatina was included on the Voyager Golden Record that was sent into outer space. So, aliens, if you’re reading this, listen to the Cavatina. If you have a heart, you will lose it.

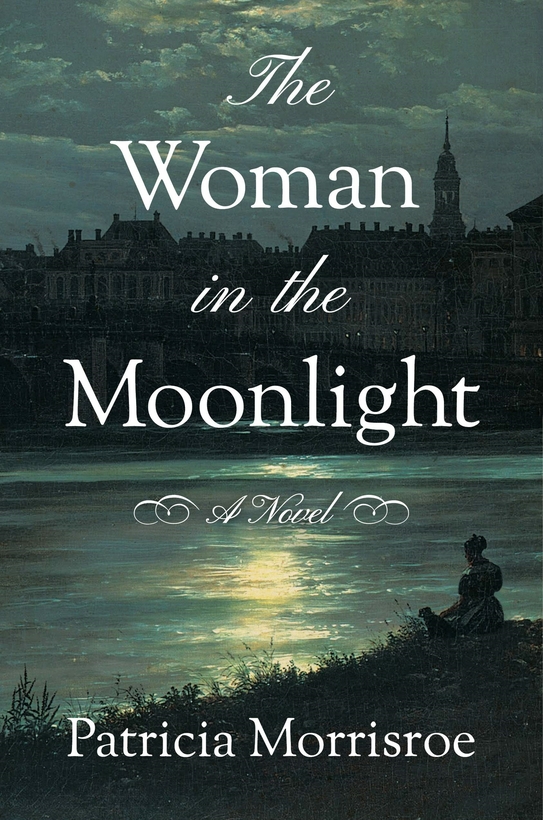

Patricia Morrisroe’s The Woman in the Moonlight is out now from Little A