Among the unknowable number of people who have been adopted as newborns, there are two camps. Those who feel a kinship with their birth families, and those who don’t.

Many adoptees are happy to live with zero knowledge of their genetic forebears and birth stories. For others, whose past has been purposefully hidden, the need to know becomes an obsession. They spend huge amounts of time and money searching genealogy Web sites and offering DNA samples to hunt down their heritage. They know that many of these searches can end in heartache. Still, they press on.

At some level, every adoptee fills the void of their birth story with a fairy tale and believes that their search will reveal not an ordinary tale of a mother unable to raise a child but a connection to a family that will transport them into a different and fabulous life that they had always imagined.

It never happens.

Except when it does.

The adoptee was American, a consultant and mother of two. In January 2015, at age 49, she composed a message to an Italian man with the subject line “Making contact after 50 years.”

“My name is Nikki Carlson,” she wrote. “I live in Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. I was born on September 21, 1965 to Nannette Cavanagh and [an] unnamed father, and was given up for adoption at birth. Nannette says that you are my father.”

The man who read those words was Mario D’Urso. Mario had lived his life in near perpetual motion, and at 74 had only just begun to slow down.

His thoughts that winter had turned to his legacy. The scion of an aristocratic Neapolitan family, Mario was a banker and senator in Italy who was close to the Agnellis and once worked for Henry Kissinger. His family welcomed Jackie Kennedy on her first trip as First Lady to their villa on the Amalfi Coast, a visit that started a lifelong friendship.

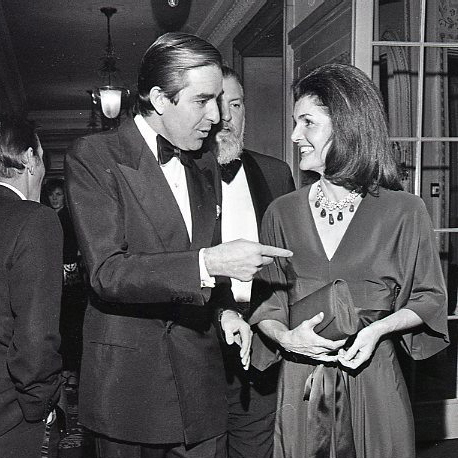

Mario was best known as the face of the European jet set of the 1970s and 1980s. The paparazzi photographed his fling with Princess Margaret in 1978 and flitted like moths around his friendships with Audrey Hepburn, Imelda Marcos, kings, presidents, and tycoons. His constant parties went on till dawn.

In 2011, Vanity Fair honored Mario’s perfectly tailored aesthetic by naming him one of the world’s best-dressed men. By then he was in a relationship with a younger man, though his position in the crustiest layer of the Old World’s upper crust compelled him to keep it discreet.

Until that moment, no one in Italy knew he had a child—not least Mario himself.

“I was born … to Nannette Cavanagh and [an] unnamed father, and was given up for adoption at birth. Nannette says that you are my father.”

If Mario harbored any doubts, he didn’t display them in his e-mail reply. “Dear Nikki, thank you. Will call you in the next few days as I don’t feel well with a terrible flu. Of course will be delighted to see you in Rome. Will keep in touch. Love, Mario”

Love, Mario. For Nikki, the words were electric. She had hoped for this her entire life.

The first whispers of Nikki’s existence appeared in the Italian tabloid press on the day of Mario’s funeral in June 2015. They now call her la figlia segreta—the secret daughter.

The secret daughter has spent her life since then trying to bury that name.

Nikki is well known in Minneapolis for her consulting and public-relations work with lawyers, politicians, and businesses. She has run local and national political campaigns, and for 20 years led the county’s Democratic Party.

What most in her circle don’t realize is that she’s been enmeshed in a transatlantic legal battle with Italy’s aristocratic and political elite, quarreling over an estate valued at 20 million euros.

Many have dismissed the ordeal as a fight over money, but Nikki says that’s never been the point. She wanted the truth to come out.

“My whole existence was based on lies and secrets,” Nikki says. “All of this had to happen.”

A Baby Is Born

Margaret and Mario, blared the headline of London’s Daily Express in August 1978. The queen’s sister had taken refuge on the beach from another troubled relationship, and her host was Mario D’Urso at his family villa in Conca dei Marini, south of Naples. For all the attention paid to it in the press, which D’Urso did little to deflect, the affair itself “was nothing,” says Reinaldo Herrera, husband of designer Carolina and a longtime friend of D’Urso’s.

By then Mario was an international banker with a title, friends in the highest places, and an unquenchable thirst for fun and travel. He probably had little memory of a brief fling he’d had in the mid-1960s with the 20-year-old daughter of a New York politician, while he was studying law at George Washington University. Whether he knew that union would bind the two together forever is unclear.

Nannette Cavanagh’s father was the deputy mayor of New York City. She graduated from an all-girls Catholic high school and was presented by her parents as a debutante in 1962.

But an unwed pregnant daughter was a political liability to a Catholic elected official back then. Mothers giving birth to children “out of wedlock” were such a scandal that by the mid–20th century adoption itself was given an official shroud of secrecy by nearly every state (a practice that only in recent years has begun to be dismantled).

So the young Nannette was whisked off to California, where she gave birth to a daughter at the Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Los Angeles in September 1965.

Until that moment, no one in Italy knew he had a child—not least Mario himself.

It’s not known where Nikki spent her earliest years, but she was adopted as a two-year-old by a couple in Prior Lake, an outer suburb of Minneapolis. As was customary at the time, a new birth certificate was created, listing her as the daughter of her adopted parents. The original birth certificate, with her birth mother listed and her birth father not, was sealed from view by the state of California.

Nikki’s new parents, who ran a successful construction company, chose adoption after being unable to conceive following their first child. They leaned conservative and favored big-game hunting and gun rights—everything Nikki was not. She grew up in middle-class comfort, but she was miserable.

In the Minnesota River Valley, Nikki’s street ended at a fence, with a field beyond. That was the backdrop of a recurring dream about her birth mother—the woman who would rescue her from the life that she never felt was hers.

“I dreamed that her face would appear in the sky over the trees at that field, and she’d say, ‘Don’t worry, I’m coming to get you.’”

Nikki’s dream wasn’t all fantasy. Only months after the world had feasted on a phony royal romance in Italy, a private investigator was prowling around Minnesota looking for a child.

The investigator called a local lawyer named Paul Thomsen and told him this story: a New York woman had given a newborn up for adoption and now wanted to establish contact. The search had led him to Prior Lake.

In 1979, Thomsen contacted Nikki’s adoptive parents and set up a meeting. But they kept that meeting secret from their then 14-year-old daughter, and didn’t talk about it until she was a mother herself.

Nikki had gotten pregnant in college, at age 20, and in 1990 was a single mom raising a toddler named Victoria. She was more determined than ever to track down information about her birth parents, who now had a granddaughter, but the state of California refused to release her original birth certificate.

Only after Nikki reached that dead end did her adoptive parents reveal the 1979 meeting with Thomsen. Nikki was appalled that they had withheld that information for more than a decade. But this was the breakthrough she had waited for.

She called Thomsen, who told her to write a letter to his client, whom he couldn’t name. After she did so, the lawyer said he would pass it on.

“I dreamed that [my birth mother’s] face would appear in the sky … and she’d say, ‘Don’t worry, I’m coming to get you.’”

A year went by. Then, in 1992, the call from her birth mother finally came.

“I felt triumphant,” Nikki recalls. “My life was going to change. She would love me unconditionally, and open up a whole new world for me.”

Yet these reunions are rarely so simple. Nannette was by then about to marry her third husband, George Herrick, after having children with her first two.

Nikki and Nannette met at a restaurant in New York City in October 1992, and again in April 1993, in Washington, D.C.

Nikki could sense Nannette distancing herself. After their second meeting, Nannette was increasingly hard to reach. Then she told Nikki that she no longer wanted a relationship. Don’t ever call me again, she told her.

Nikki felt as if the air had been pressed out of her lungs. For the second time in their lives, Nannette had decided to push her daughter out. (Nannette Herrick declined repeated requests for comment.)

Who is my father?, she had asked Nannette.

You don’t want to know, came the answer.

Nikki did want to know. It took another 20 years before she learned it.

According to Nikki, in January 2015, one of Nannette’s ex-husbands, Arthur Kreizel, summoned Nikki to his estate in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, saying he had recently suffered a stroke and didn’t want to take the name of her father to the grave. She booked a flight immediately and later that day stood before him in his villa. It was there she first heard the name Mario D’Urso.

The pages and pages of Google search results about Mario were both astonishing and affirming. Nikki felt far more kinship to this man than to her birth mother. (Nannette was by then ensconced in the social circles of Newport, Rhode Island, retired from P.R., and busy entering her wire fox terrier in dog shows.)

The next six months are burned into Nikki’s memory. It started with a phone call from Mario a week after her e-mail. He wanted to see her right away.

Nikki flew to Milan in March, her earliest opportunity. They arranged to meet for lunch in the lobby of a hotel near the Duomo. He walked in, and she fell into his arms. Two strangers, one 74, one 49, embracing in a hotel lobby.

Over lunch, Nikki asked him if he knew he had a daughter. He said he knew there had been a pregnancy, but nothing else. He had thought, over the years, that he might have a child somewhere in the world.

“Are you my father?” she asked him.

“I think so,” he said.

After a week, Victoria joined Nikki in Milan. Mario introduced them to his many relatives and friends as his daughter and granddaughter. For all his well-publicized dalliances with famous women, Mario was a lifelong bachelor with no other children.

Their main handler was an assistant to Mario. Outside the presence of his employer, Nikki says that his helpful manner vanished and his skepticism about these newfound family members was palpable.

Muted in the beginning, that hostility among some of Mario’s inner circle would soon burst into the open.

A Reunion Cut Short

The village of Conca dei Marini is built into the steep Amalfi Coast, homes crusted like jeweled barnacles on the rocky cliffs above a turquoise sea. In mid-March 2015, Nikki and Victoria looked from a balcony out onto the waves.

Generations of D’Ursos had lived and entertained in their villa there, and no other place was more identified with his family’s position in Italian society. The guest book had hundreds of signatures from visitors including Princess Diana and, earlier, Jackie Kennedy, whose visit there introduced her to Gianni Agnelli and an opportunity to water-ski far from her troubled marriage to the president of the United States.

A week later, Nikki and Victoria went back to Milan to rejoin Mario, who said he’d been at a clinic in Switzerland to be treated for the cancer spreading in his lungs and liver.

When they saw him again, his manner seemed to have changed, and he was talking openly about what he would leave behind.

Meeting for dinner in the Brera district, Nikki remembers Mario saying he wanted to leave her a substantial legacy. Unbeknownst to her, he had written on a single sheet of paper his last will and testament, asking that aside from five million euros for Roberto Simeone, his lover, the rest of his estate should be distributed by law. Nikki was not named. Three days later, Nikki said good-bye to Mario and flew home.

Back in the States, Nikki called Mario regularly. They spoke maybe 10 times, and she could hear him getting weaker. Then she couldn’t get through at all.

It was clear Mario was ailing, but also that whoever was picking up the phone wouldn’t put him on. On June 5, 2015, Victoria called Mario’s phone and a woman answered. She was sobbing.

Victoria called her mother and delivered the news. Less than six months after Nikki found him, her father was dead.

“Are you my father?” she asked him. “I think so,” he said.

Tributes were published around the world. The New York Times obituary noted that Mario was a banker at Lehman Brothers and then a public servant in the government and Italian Senate in the 1990s. “He was unique in combining his civic and corporate responsibilities with mingling in the international jet set,” it read. “He was generous and compassionate, well-known and well-loved.” There was no information about survivors.

On an overcast June morning in Rome, a tabloid photographer set up shop outside the Church of San Roberto Bellarmino. A succession of shiny vehicles discharged European notables in dark suits and elegant dresses, including friends Maria Sole Agnelli, daughter of Gianni, and Fausto Bertinotti, the former head of Italy’s Communist party, as well as the deceased’s sister-in-law Inès de La Fressange, the French model and designer. Each was photographed as if arriving on the red carpet of a Hollywood premiere.

At the funeral, there were whispers about a crazy American lady who might show up claiming to be the long-lost daughter of Mario D’Urso. Keep your distance, people told each other.

Nikki, Victoria, and Adriana, her youngest, arrived wearing new black dresses. Someone had told them that the funeral would be happening days later, but Nikki says she discovered the correct date from one of Mario’s housekeepers.

Nikki and Adriana sat down together in the pews, while Victoria moved up to the section reserved for family, and was told she couldn’t sit there.

Nikki was seated next to a friend of Mario’s, who said to her, “This is outrageous. They are trying to keep you out. Look! Mario is in a pine box. They plan to cremate him. Go to the front. Announce you are his daughter. They can’t get away with this.”

Nikki kept her seat, and her tongue. But his words stayed with her.

Over the next eight years, her life would become entangled with Mario’s network of survivors. Court battles would break out on both sides of the Atlantic. Legal bills would soar. All of this would transpire as a global pandemic erupted in Italy and turned the world upside down.

A Legacy Battle Begins

Within weeks of Mario’s funeral, the Italian press were laying out the details of his will. With the help of some lawyer friends, Nikki got a copy of the will that August.

Signed on May 16, 2015, less than three weeks before Mario’s death, and replacing the handwritten one he’d drafted, it was a detailed distribution of assets to select family members and friends, with the “residual heir” named as Francesco Serra di Cassano, the Duke of Cassano, a first cousin once removed who, with his wife, received one million euros.

Roberto Simeone remained one of the largest beneficiaries. Besides five million euros, Simeone was left Andy Warhol’s Hammer and Sickle as well as works by Picasso and Italian postmodernist Mario Schifano.

Serra, a journalist, declined to answer detailed questions about the case, but in an e-mail asserted his “very close” bond with his cousin Mario. Mario had organized Serra’s wedding and asked him to help produce a book about his life.

Serra said he had seen less of Mario in his final year, “but, shortly before his death, he called me, with full awareness of his state of health, to tell me that he had left instructions for me [with] a notary in Rome.” He said he knew nothing about Nikki’s existence until a few days after Mario’s death.

Simeone also declined to discuss the case, though he did say he regrets that it has caused a rift in his friendship with Nikki. “I miss her,” he says.

Italian law mandates that a surviving child is entitled to at least half of an estate, and Mario’s beneficiaries stood to gain the contents of the will if they could prove he had no children. Nikki felt she had to do something.

That summer, she started researching ways to get her DNA tested. She says she reached out to Simeone and asked him to send her something that might have Mario’s DNA. Not long after, a toothbrush arrived in the mail. (Simeone says he wasn’t the one who sent it.) She shipped it to a laboratory to compare with a sample of her own biology, but the results showed that whoever used the toothbrush was not related to Nikki.

The following month, the executor of Mario’s will received a letter formally notifying him that Nikki was challenging the will.

Less than six months after Nikki Carlson found him, her father was dead.

Mario’s remains had been cremated, so that winter, Nikki contacted two nieces and a nephew of Mario’s. They had shunned her at first, but now that they knew they were also disinherited, they were ready to listen.

In early 2016, Nikki and her three cousins swabbed their cheeks in the presence of lawyers and one of Italy’s top DNA experts. Without any tissue samples available for Mario, they would use close relatives to attempt to determine the match. Meanwhile, the cousins agreed to join Nikki in contesting the will.

Spring slipped by, then summer. Then, on November 17, 2016, the Roman daily newspaper Il Messaggero broke the story: “The D’Urso inheritance is reopened. An American: I am the daughter.” Someone had leaked the results of the DNA test to the press, and it was a match.

Nikki hadn’t found out about the results yet, because she was doing volunteer work in Ethiopia at the time. Her phone buzzed with a call from Italy. It was a reporter with Il Messaggero, wanting an exclusive interview with la figlia segreta.

With her battle now in the open, Nikki relocated to Italy in late 2016 for an extended stay, moving into the D’Urso complex on Viale di Villa Grazioli, in Rome.

Mario had lived in luxury in a detached apartment there for decades. But when Nikki arrived, the apartments had been stripped almost bare, the tables, chairs, sofas, beds, paintings, and sculptures carted off to a warehouse to await distribution as part of the estate.

Inside the few boxes that remained, Nikki found ephemera of Mario’s extraordinary life. Thousands of letters, photographs, press clippings. A White House Christmas card signed “fondly and affectionately” from his friend Nancy Reagan. A photo of Mario with the Pope. Many of Mario with Kissinger. An invitation to dinner at Buckingham Palace with the Prince of Wales in 2004.

Then, in a pile of loose papers, she caught sight of a telegram. Dated April 12, 1965, it was addressed to Mario D’Urso, in Washington, D.C. The sender: Nannette Cavanagh, of New York, N.Y. “Mrs. Raymond Johnson has invited us to small private luncheon this Thursday for Maurice Chevalier ‘Le Voisin’ 1 oclock. If you are here will you come. RSVP subito. Love, Nannette.”

Nikki was stunned. Nannette would have been three months pregnant with her at that time. Maybe, in the presence of a famous French crooner, she would have broken the news that Mario was going to be a father.

Then Nikki noticed something handwritten on the telegram. A single word, underlined twice: “NO.”

“The D’Urso inheritance is reopened. An American: I am the daughter.”

Though the challenge of the estate was now a matter of public record, Nikki still found herself invited to parties from some of those in Mario’s inner circle, including at Simeone’s home.

Nikki says that she remembers throwing some used tampons in the trash at one of Simeone’s parties. About a month later, back at the house for another dinner party, she went into the kitchen and opened the freezer to get some ice for her drink. Inside, allegedly, were her tampons, preserved in a plastic bag.

Nikki claims Simeone had set them aside as evidence for another DNA test that Mario’s beneficiaries hoped would show she was an impostor. Simeone says he has no memory of these events.

To win her paternity case in Italy, Nikki also had to overcome a legal obstacle in Minnesota: her adoption into a Minnesota family meant she already had a father of record.

In a Scott County court, Nikki filed the paperwork to vacate her adoption, ending the parent-child relationship that had existed for a half-century. Her adoptive parents, with whom Nikki had always had a complicated relationship, did not oppose it. In May 2018, a judge ordered the adoption vacated.

Meanwhile, Nikki and the three cousins were going on the offensive in Rome. Their formal challenge to the will accused Mario’s beneficiaries of an orchestrated campaign of deception and greed. It laid out the circumstances of Nikki’s discovery of Mario, their brief but intense time together, and Mario’s promise, over dinner in Milan, that Nikki would be included in his will.

Then, as cancer overcame Mario, the petition described how those around him intercepted e-mails and letters from Nikki. Beyond this protective cordon around the dying Mario, the most incendiary accusation concerned the second will, drawn up 20 days before his death.

By that time, the cancer had metastasized to Mario’s bones, inflicting excruciating pain for which he was heavily sedated with daily doses of morphine. Under those circumstances, could Mario execute a will that took two hours to put together and named 24 separate beneficiaries, distributing cash, artwork, and his enormous wardrobe? Nikki’s lawyers called such a thing “incomprehensible.”

Citing Nikki’s matching DNA test to Mario’s relatives, the petition called for the judge to invalidate the will, seize the assets, and restore Nikki’s status as the principal heir to Mario’s estate.

In the summer of 2018, two new parties filed to intervene in Nikki’s adoption-vacation case in Scott County. One of them was Serra. The other was the woman who had relinquished her at birth 53 years before.

In his affidavit, Serra asserted his own ties to Mario. He said that though he was a cousin, he was treated more like a beloved nephew.

Prepared by Serra’s attorney and signed and notarized in Newport, Rhode Island, meanwhile, Nannette Herrick’s affidavit portrayed Nikki as an intrusive individual who tracked her down and harassed her and her family, and described herself as a considerate woman who was merely obliging Nikki in her desire to know her. And she dismissed Nikki’s belief that Mario was her father as a theory.

“Just as I had no right to re-insert myself as a parent into Ms. Carlson’s childhood after relinquishing the child for adoption,” Nannette wrote, “Ms. Carlson should not be able to secretly force the restoration of our parent-child relationship without my consent by filing paperwork in a sealed court proceeding, and without even providing any notice to me.” Nowhere does she mention that she had hired a private investigator to track down Nikki’s adoptive family.

In early 2019, Scott County district judge Colleen G. King threw out the motions by Herrick and Serra. “Although Ms. Herrick has a legitimate interest in wanting to protect her appearances and does not want her pregnancy and illegitimate child to become public knowledge,” the judge wrote, “the Court could find Ms. Herrick waived those interests when she sought out and initiated contact with Ms. Carlson.”

Nikki had won the first legal battle. With the obstacle of the adopted status cleared away, her lawyers in Rome immediately renewed the claim.

A court hearing was scheduled for February 2020. That same month, the Italian government suspended all flights to and from China. The move was futile. Within weeks, Italy was the epicenter of the West’s coronavirus pandemic.

Then, in early 2021, things lurched back to life. A new judge was on the case, and she ordered Nikki to come to court in Rome and submit to another DNA test to settle the paternity question.

Someone had discovered a tissue sample taken from Mario’s lung and stored in a laboratory in Milan. Now, instead of evaluating a DNA test based on relatives, the court could compare the genetic fingerprint of the two people in question. The judge appointed her own DNA expert, who traveled to fetch the tissue sample, put it in a briefcase, and handcuffed the briefcase to her arm for the duration of the trip back to Rome.

A few months later, the results came back. The DNA showed that the probability that Mario was Nikki’s father was the equivalent of 99.99976867 percent. The debate, for the purposes of the law, was over.

It was after midnight, in January 2023, when the message from Rome finally arrived. Her lawyer had sent her the judge’s ruling, and on her phone Nikki skimmed the Italian legalese and spotted words that could not be clearer: the court “ascertains and declares that Nikki Carlson, born in Los Angeles, USA, is the biological daughter of Mario D’Urso, born in Naples and died on June 5, 2015 and, as a result, provides that Nikki Carlson assumes the parental surname.”

In a 10-page ruling, the judge found that Nikki’s paternity had been established by the DNA tests, causing Mario’s will to be automatically revoked, because of a provision in Italian estate law meant to prevent children of the deceased from being disinherited if their existence wasn’t known or established prior to their death.

Serra was ordered to pay Nikki’s legal fees. Nikki was ordered to add “D’Urso” to her name.

The results came back. The DNA showed that the probability that Mario was Nikki’s father was the equivalent of 99.99976867 percent.

It took a few weeks for the Italian tabloids to catch up with a story they had pumped for years. “Mario D’Urso is Nikki Carlson’s father,” said one. “Mario D’Urso had a daughter: his inheritance will go to Nikki Kay Carlson,” said another. The February issue of Diva e Donna, a women’s magazine, featured Nikki and her father on the cover: “The 24 million Euro inheritance: All to the secret daughter, and Bertinotti has to give back the Warhols.”

Within days, letters from Nikki’s lawyers were sent to the beneficiaries. To the lover, Roberto Simeone: “Ms. Nikki Carlson hereby invites and warns Mr. Roberto Simeone to return the … legacies, namely the amount of EUR 5,000,000 … and the aforesaid paintings.”

It’s not clear to Nikki whether she’ll ever see a single euro, but she says that was never the point. “She wanted to know who she was,” says Dan Johnson, a Minneapolis banker and longtime friend of Nikki’s. “She always knew she was more than someone who was just adopted. She wanted desperately to know of her origins.”

For now, Nikki is happy to abide by the one obligation handed down by the judge. Her new name has already been chosen: Maria Nicoletta D’Urso.

James Eli Shiffer is a Minnesota-based journalist. He is the author of The King of Skid Row: John Bacich and the Twilight Years of Old Minneapolis