Before I picked up this book, risking elbow strain from its hefty bulk (605 crammed pages), I was skeptical that there was anything new and original left to uncork about the epic, gaudy romance of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, the roving monarchs of the jet age. I was mistaken.

Erotic Vagrancy, its title taken from a 1962 Vatican newspaper editorial condemning Burton and Taylor’s licentious carryings-on and the bad example it set for the laity, tells us loads that we didn’t know before and often more than we need to know, plunging the reader in a bacterial vat of boogie-woogie detail that will leave some gasping for relief. Certain biographers are taker-outers, others are putter-inners, and Lewis is the latter in excelsis.

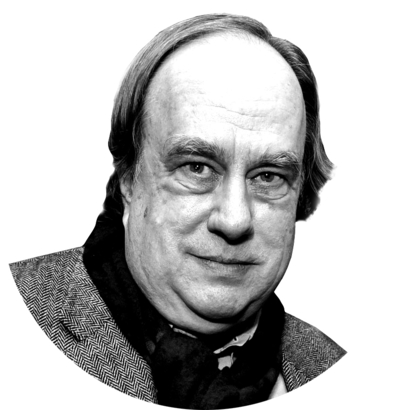

But if Erotic Vagrancy is comprehensive, immersive, and kaleidoscopic until it seems almost bug-eyed, one thing it’s not is boring. It has drive, brio, and a punchy point of view. As with his previous biographies of extraordinarily gifted ego monsters (Laurence Olivier, Peter Sellers, and Anthony Burgess among them), Roger Lewis makes no pretense of judicial biographical detachment, nor does he fawn at the altar of celebrity. He’s in there swinging, chucking around opinions and connecting wild dots.

Plus, and how rare this is in biography, he’s funny. Any show-business history that makes you laugh as much as this one is a keeper.

The Burton-Taylor Road Show

It all begins with Cleopatra (1963 A.D.), the lavishly mounted tale of imperial love and intrigue that busted up two marriages (Taylor was married to the glutinous crooner Eddie Fisher at the time, Burton to the stalwart Sybil née Williams), nearly brought down a studio (Twentieth Century Fox), and ignited the greatest publicity bonfire Hollywood had ever seen.

Despite her violet eyes and queenly hauteur, the portly Taylor was miscast as Cleo—when they unrolled her from the rug she should have kept rolling—and Burton’s basso profundo entreaties bordered on camp, but there’s no accounting for star power and sexual chemistry. Together, they transcended the tawdry spectacle and were joined in unholy cinema matrimony, grappling partners with asp-ish tongues.

Under Mike Nichols’s crafty direction, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) brought out the worst-best in both. It allowed Taylor to bust out of her girdle and let loose a cawing, mocking harridan, and it showcased the soul-sick, ulcerous power Burton had first disclosed in The Spy Who Came In from the Cold the year before.

If only the two had stopped there! So many wilted literary adaptations seemed to dampen their fires, while others (the 1967 Shakespearean slapstick of The Taming of the Shrew) were too rumbustious. The nadir was reached when in 1970 they made a guest-star appearance on Lucille Ball’s Here’s Lucy sitcom, an exasperating experience that made Burton want to wring Lucy’s scrawny neck. No matter how high one climbs, the indignities of an actor’s life never cease.

Together, Burton and Taylor transcended the tawdry spectacle of Cleopatra and were joined in unholy cinema matrimony, grappling partners with asp-ish tongues.

If Burton and Taylor’s movies were hit-and-miss, they never wavered in holding the public in thrall. Cinema simply could not compete with the tempestuous chapters of the couple’s off-screen melodramas and extravagances, a “chaotic Ruritania” on wheels in which they arrived at five-star hotels with mountains of luggage—“Why do the Burtons have to be so filthily ostentatious?” wondered Rex Harrison aloud—only to leave the luxury suites in foul shambles, the traveling menagerie of Taylor’s un-housebroken dogs, cats, and occasional simian peeing and pooping all over the place.

Their road show was a rock-star lifestyle for which Taylor was more suited. Like Elvis Presley, Taylor was self-afflicted with prescription drugs, ravenous eating habits, a craving for jeweled regalia, and the need to be surrounded by a flotilla of flunkies. In contrast, Burton was more bookish and reserved (his diary reveals a deeply literate devotional sensibility), conflicted with “a puritan conscience, but a libertine’s taste,” as Lewis observes. He also could be sullen, brooding, given to snarling insults and being a sentimental bore about his Welsh upbringing—in short, no fun when he was boozing to excess, and excess for him was the norm.

For a long feverish spell, he and Taylor couldn’t stay apart, divorcing, remarrying, then divorcing again, always under a blazing spotlight. The marry-go-round continued after their second divorce, with Taylor wedding a politician (John Warner, the kind of “distinguished” Republican senator they don’t mint anymore), and later improbably saying “I do” to mullet-haired construction worker Larry Fortensky. Lewis reminds us that the bridesmaid at this bizarre ceremony at Michael Jackson’s Neverland Ranch was Jackson’s chimpanzee sidekick, Bubbles. Considering how things turned out, Lewis cracks, “Fortensky would have been better off marrying the chimpanzee.”

Cinema simply could not compete with the tempestuous chapters of the couple’s off-screen melodramas and extravagances.

Posterity has dealt Burton and Taylor unequal hands. Taylor not only defied the odds and a host of dire prognoses, surviving one medical crisis and one hospital stay after another, but bounced back even higher. “Maladies for her brought rhapsodic moments,” Lewis writes—jolts of rejuvenation.

Although Taylor qualified as Old Hollywood, a crowning achievement of the studio system, she never ossified or became a quaint old dear. She stayed with the times, heroically becoming a spokesmodel and fundraiser during the AIDS crisis (when nearly everyone else in the entertainment world was hiding behind the ferns), creating a phenomenally successful fragrance brand (her “final dispersal was to be as a perfume,” as Lewis nicely puts it), and keeping tabs on younger filmdom through phone chats with foxy Colin Farrell.

Burton, a more traditional chap out of sorts with the Zeitgeist, died from drink at the age of 58, a burnt-out case trailing unfulfilled promise in his wake. If only he hadn’t been bewitched by “Elizapatra” and diverted from his true high purpose as an actor, professional mourners lamented. They still do. For more than a half-century it’s been de rigueur to echo Burton’s cri de coeur that he never played King Lear, but, as Lewis sensibly asks, “So what?” Who needs another grizzled gazoo ranting on the blasted heath? Burton’s true immortality was to be found elsewhere, at Elizabeth’s side.

James Wolcott is a Columnist at AIR MAIL. He is the author of several books, including the memoir Lucking Out: My Life Getting Down and Semi-Dirty in Seventies New York and Critical Mass, a collection of his essays and reviews