Samuel L Jackson is in London, making a superhero television show called The Secret Invasion. He has been coming to Britain since 1980. “Yesterday I went through Shepherds Bush,” he says. “Where I used to buy weed.” Another time he went to Blackpool. “I don’t know if I like Blackpool that much.” Soon he heads back to Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife, LaTanya, a fellow actor. He has an award to pick up — the Academy honorary award, a statuette given to stars who, awkwardly, never won an Oscar. Jackson has only one nomination, for Jules in Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

“I should have won that one,” he says, smiling. He also cites his role as the junkie in Jungle Fever as another that got away. He was beaten to a nod by two of the cast of the gangster film Bugsy.

“My wife and I went to see Bugsy,” he says. “Damn! They got nominated and I didn’t? I guess Black folk usually win for doing despicable shit on screen. Like Denzel [Washington] for being a horrible cop in Training Day. All the great stuff he did in uplifting roles like Malcolm X? No — we’ll give it to this motherf***er. So maybe I should have won one. But Oscars don’t move the comma on your check — it’s about getting asses in seats and I’ve done a good job of doing that.”

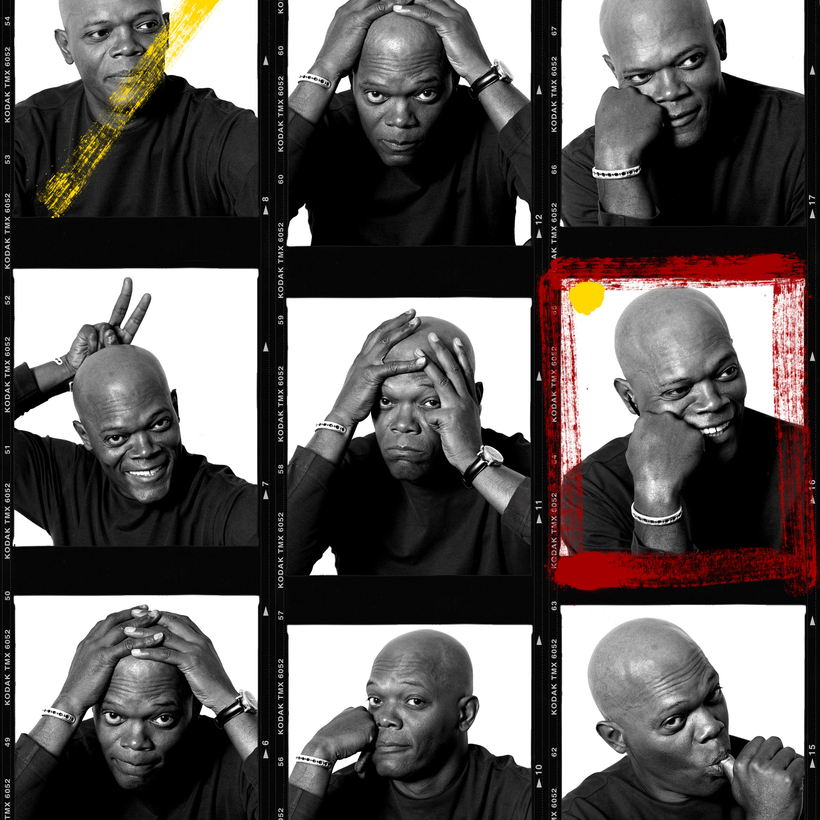

This is Jackson to a tee. He sits there, so enormously relaxed spilling out opinions that he often just chuckles, puts his feet up. Wearing clear-framed round specs, his voice, as you know from more than 150 films, rises, falls and squeaks when he finds something daft.

His drug years, his mother’s dementia, Joe Rogan — it’s a verbal storm from a 73-year-old who happens to be the highest-grossing actor of all time. The combined box office from his films is $27 billion — his closest real rival is Robert Downey Jr at $16 billion.

Ten appearances as Nick Fury in Marvel films help, as does Jurassic Park and three Star Wars movies. When Jackson was making his third Star Wars in 2004, George Lucas told him that, when the film came out, Jackson would usurp Harrison Ford at the top of the earners chart. “I’m going to do that before then,” Jackson said. “Because I’ve got this little movie coming called The Incredibles.”

Anyway, he is pleased about the Academy honorary award and says he will be polite in his speech, although he goes on to say that he is tired of elitism, and luminaries such as Martin Scorsese who have recently derided Marvel films.

“Oscars don’t move the comma on your check — it’s about getting asses in seats and I’ve done a good job of doing that.”

“All movies are valid,” Jackson says. “Some go to the cinema to be moved dearly. Some like superheroes. If somebody has more butts on seats it just means your audience is not as broad. There are people who have had successful careers but nobody can recite one line of their parts. I’m the guy who says shit that’s on a T-shirt.”

“They should have an Oscar for the most popular movie,” he continues. “Because that’s what the business is about.” Spider-Man: No Way Home made $1.8 billion — should they give it an Oscar? “They should! It did what movies did forever — it got people to a big dark room.”

Now for something utterly different and a new Apple TV drama starring Jackson as the lead in The Last Days of Ptolemy Grey. Based on a Walter Mosley novel, it tells of a man with dementia offered a miracle cure, and if it were a film it might have led him to that Oscar.

Jackson has done serious before — notably in A Time to Kill, on trial for the murder of the men who raped his daughter — but not for a while. This one is personal, though. Dementia runs in his family. His mother, grandfather, aunt, uncle — they are why he took the role.

“I remember the last time my mother called my name,” Jackson says. She was Elizabeth, a factory worker and single mother, who died in 2012. “She was watching TV and a film of mine was coming out,” he says. “I popped up on the screen and she looked at me and said, ‘Oh, Sam.’ That was it.” After that he would look at her trying to figure out who he was. She would get angry. “I don’t know if she was running through faces in her mind or seeing me from when I was a little person. Or as this big person.”

Given the family history, is Jackson afraid? “Of course,” he says. “I have times when I can’t remember a name that I know I know. Or walk in a room to get something and go, ‘Why am I in here?’ But I also still remember pages of dialogue a day. So, do I think about it? Yes. Am I worried? I’m 73 … 74? 73 …” He laughs. “See, like that! But it had happened to my mum and my grandfather by now. So I think I’m OK. For the moment.”

Physically he is more than OK — a super-fit man with a skin-care regime who tends to be in the sort of high-octane action role previously not associated with actors his age.

“Yet people know I’m 73,” he says. “I’m not going to get into a fistfight with some 20-year-old. But I’ll shoot him. I can do that. If a guy hits me, I’m down. I’ve got 15 seconds of fight, so I don’t put myself in those positions. Let’s not stretch credibility.” He has a bad knee, so his characters will often be shot in a leg or twist an ankle so Jackson can limp. In Captain Marvel they used digital tricks to de-age him decades, like in The Irishman. “That’s the worst,” Jackson barks. “I don’t know what company Marty [Scorsese] used but it wasn’t the company they used for Captain Marvel.”

What a blast he is. So many bases are covered it feels like a game of baseball. On occasion, while waiting for a question, he pulls a quizzical face and you worry he is about to shut you down — but he just keeps on talking.

“I’m the guy who says shit that’s on a T-shirt.”

This is how conversation goes. We talk about politics in films and he says: “What’s the politics of Snakes on a Plane?” — his thriller about, erm, snakes on a plane. I say some think that, post-9/11, it was about the need for air marshals. “Every opinion is not precious, but everyone seems to think they are,” he says. He tells me that his daughter, Zoe, 39, who also works in film, stopped him going on social media as much as he did. His edgy humor did not translate to Twitter and he was always one post away from getting canceled. “People are always calling me about doing a podcast, but I can’t talk for an hour without saying something f***ed-up.”

And so to the blowhard world number one podcaster Joe Rogan. Not because of vaccine skepticism, but his use of the n-word. “He is saying nobody understood the context when he said it,” Jackson says, rolling his eyes. “But he shouldn’t have said it. It’s not the context, dude — it’s that he was comfortable doing it. Say that you’re sorry because you want to keep your money, but you were having fun and you say you did it because it was entertaining.”

So his use of the n-word lacked context? “It needs to be an element of what the story is about. A story is context — but just to elicit a laugh? That’s wrong.” Jackson has worked with Tarantino six times. “While we were rehearsing [the slave movie] Django Unchained, Leo [DiCaprio] said, ‘I don’t know if I can say “n*****” this many times.’ Me and Quentin said that you have to. Every time someone wants an example of overuse of the n-word, they go to Quentin — it’s unfair. He’s just telling the story and the characters do talk like that. When Steve McQueen does it, it’s art. He’s an artiste. Quentin’s just a popcorn filmmaker.”

What a load of stories. Still, there are some memories that he would rather forget. Born in 1948, he was brought up in Tennessee before going to college in Atlanta and moving to New York in 1976 to become a stage actor. A lot of drugs followed. One idea Ptolemy Grey has is that we lose our minds so we can forget what hurts us and Jackson has bad memories from that era. He hurt people. “And there are things from then I really don’t remember!” He laughs. “But I didn’t like that point in my life.”

So let us end on a positive. His latest role is about memory. He has already talked to his daughter about what to do if his mind slips. “Don’t dress me up and send me onstage and pretend I’m OK,” he says, laughing. “I’ve seen that with other actors.”

I ask what he would most want to cling on to later on. “There are performances that I’ve done,” he says. “Times I was so happy to get to the theater. Then there was when I got sober. There’s a correlation between that and success. I did Jungle Fever three days out of rehab, not needing makeup because I was detoxing. I knew as soon as I got high before work and high at work again this was all going to crumble. So I go back to getting clean.”

His is a life of exceptional adventure. The Academy honorary award? It’s a belated prize for a mantelpiece of memories of fame and family. “I go back to the wonderful times after I got sober of experiencing my daughter,” he continues about what means most. “Those are things I want to hold on to.”

Jonathan Dean is a senior writer at the Sunday Times Culture section and the author of I Must Belong Somewhere: Three Men. Two Migrations. One Endless Journey