“Don’t you ever get tired of being a fat slob?”

To hear someone say that out loud is shocking, but for Sandra to hear it from her therapist was just plain weird, especially in group therapy. We were all, at that point, completely unaware that Magda, the woman with whom we’d entrusted our innermost secrets for probably 20 years, was sinking into senility.

Magda was seated in her chair, wearing a polka-dot blouse and plaid skirt. Her shoes were plain black low pumps with anklet socks. Her hair had braids wrapped around her head. The only thing missing was the soundtrack from The Sound of Music, which would have been appropriate since she was born in Vienna to a musical conductor and a ballet dancer; the latter pirouetted out of her life when Magda was a child, leaving her to her father, whom she adored.

Lately, she’d been nodding off during the session. At first, we tried to wake her up. Then we realized it was safer when she was asleep because her comments were increasingly devastating. So we’d just go ahead and manage on our own, diagnosing one another. “Where did you get that top?” she said to Vera. “At a yard sale in the city dump?” To Linda, who had been recently thrown over by her married lover, she said, “Well, if you insist on screwing another woman’s husband, you get what you deserve.”

What was coming next? The fear in the room was palpable. Who would be the next target? Was it John, who was afraid of elevators, and planes, and even thunder? On cue, Magda asked him, “Wouldn’t you be better off dead than living like this?” Next up was Rhonda, with her soulful eyes and half-bitten fingernails, who always sat with one arm over her head, clinging to the wall, looking as if she were belowdecks on a rocking fishing boat hoping not to vomit. “Why are you so dull?,” Magda asked her. “Don’t you ever have anything interesting to say?”

Since we were not allowed to speak to each other outside the group, where we could compare notes, it was all very confusing. To make matters worse, Sandra was obese, Linda was sleeping with someone else’s husband, and, God knows, everyone was silently aghast at Vera’s outfits with her Dutch Boy caps and artificial flowers pinned on them. She usually finished off her outfits with puffy skirts over Paisley pants. It was always Halloween with her. And finally, we all were bored to death by Rhonda’s pathetic and ongoing depression.

Lately, she’d been nodding off during the session. At first, we tried to wake her up. Then we realized it was safer when she was asleep because her comments were increasingly devastating.

No one suspected the truth. We just knew that Magda was right, as usual. In fact, to add to the confusion, she was just a nastier version of her earlier self. Telling everyone exactly what she thought was Magda’s M.O. “Are you on drugs?” she asked me, early in my therapy. What a witch, I thought. I took a small dose of Valium this morning. How did she know?

She took copious notes during the sessions, and I often wondered what she was writing, but I was too afraid to ask. She had an imposing demeanor like a Gulag guard, and I just let things slide. One time I told her that my husband would send her a check, and she rose from her chair, hovered over me like a giant bat, and said, “You will pay for your own therapy.” After that, you can rest assured that I wrote every check.

The thing I liked about Magda, and what kept me there all those years, was that she was the opposite of my parents. I was raised in an undisciplined environment by a big, affectionate family. My mother was the queen of unconditional love, and as a result, I had no boundaries and didn’t know which way to turn half the time. Magda was strict. No gray areas for her. She knew the answer.

Should I drop the idea of being a TV producer and go to law school? “Absolutely not. You don’t have the attention span for that.” Check. She even involved herself in real-estate decisions. Should I buy the apartment when the building goes co-op? “Of course you should. You will double your investment.” Whenever I had a decision to make or when I came to a fork in the road, I just asked myself, “What would Magda do?”

But her behavior got worse every session. One day she confused me with someone else in the group. Rhonda was always talking about her mother, who had been dead at least 30 years but was still somehow ruining her life. Whenever it was Rhonda’s turn to tell us about her week, she’d drag her dead mother into the room. The day came when my mother actually did die, and I informed the group of her passing. Magda said to me, “Oh, you’re always talking about your mother.” You’d think I would have figured out that she was not all there that day. But I wasn’t ready to acknowledge it yet. And at that point, she had me so bamboozled, I wasn’t sure if I was always talking about my mother.

Telling everyone exactly what she thought was Magda’s M.O. “Are you on drugs?” she asked me, early in my therapy.

Months went by, and soon she forgot almost everything. She even forgot to charge us. It was bad. But no one left the group. We even admired her ability to fall asleep so easily, thinking, “Look at that, so free of anxiety that she can nod off as if she just got a 90-minute massage.” It did make me wonder if she wasn’t fast asleep during my private sessions, as she was silent most of the time while I was lying on the couch yammering on about some Oedipal thing or other. Maybe all Freudian analysis is just another way of shrinks’ saying, “Hey, I need a nap, and there’s no time like the present.”

One day, Rhonda, the wall hugger, walked in late to the session. Rhonda was never, ever late in all the years in this group. This was a woman who alphabetized her bookshelf, organized her sock drawer, and planned tonight’s dinner a month ahead. She was breathing heavily as she entered the room. “Oh, I’m so sorry I’m late. There was a mugging on the No. 1 train.” Magda looked at her and said, “Oh, you are always late.” Upon hearing this unjust accusation, Rhonda became hysterical and started crying.

“No, no, no. She’s never late,” we all seemed to be yelling at the same time. “Never, never, never. This is the first time!” But even with our vociferous defense of her, Rhonda was inconsolable. It’s one thing to be told you’re boring and have nothing interesting to say. It’s another thing for a girl with O.C.D. to be told she’s always late.

We turned to Magda to do something, anything, but amid all the yelling, she had fallen asleep. No one tried to wake her. After a few minutes, there was a palpable sigh of relief. “Let’s go,” I said. We got up, silently put our coats on, and left the room for the last time—all paid up.

I think of her from time to time, and as I write this, I even miss her. After all, very few people will actually tell you the truth.

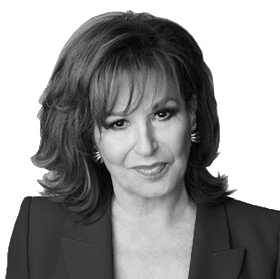

Joy Behar is a comedian and a co-host of The View. This is a chapter from her memoir in progress, which will be published by Regalo Press in 2025