As Israel battles back after the humiliation of the Hamas attack on October 7 of last year—with the highly destructive war in the Gaza Strip now metastasized into a war to the death against Hezbollah in Lebanon—the country’s intelligence services are working to remove the damning stain of failure.

“We weren’t responsible,” one Mossad officer told us on condition of anonymity, “because it’s the army and other agencies that watch the Gaza border.”

But still, the officer added, “I even feared for my family’s safety, and we all wondered how we’re going to restore our deterrence.”

“Deterrence” is a key word for Israeli strategists. Deterrence means ensuring that everyone in the Middle East is afraid of mighty Israel—and the Mossad is the agency, in effect a powerful brand name, that is at the tip of everyone’s tongue when assessing whether Israel is up or down.

For months, after the massacres and kidnappings of October 7, Israel was in a downward spiral. But, lately, the country’s spies are on a highly visible roll: hunting down and assassinating Hamas and Hezbollah leaders in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran. Precise intelligence is also guiding air-force strikes in Gaza and on Hezbollah arms caches in Lebanon. Israeli officials insist that they try to minimize civilian deaths, but last Monday, Israel launched a series of strikes on Lebanon that killed close to 600 people, making it the deadliest week in that country since the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah war.

Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu told the United Nations on Friday that “there is no place in Iran that the long arm of Israel cannot reach. And that’s true of the entire Middle East.” Not long after Netanyahu spoke in New York, Israeli bombs pulverized Hezbollah’s underground command center in Beirut and killed the terrorist group’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah.

Lately, the country’s spies are on a highly visible roll: hunting down and assassinating Hamas and Hezbollah leaders in Gaza, Lebanon, Syria, and Iran.

A decades-old pattern is re-emerging, in which Israel’s achievements are often exaggerated or distorted, but the Jewish state does not bother to issue denials or clarifications.

Israel’s spies—and generations of political leaders—prefer to let the Mossad mystique work its magic. If assumptions and fictional embellishments intimidate the nation’s enemies, all the better.

Take the attack on Hezbollah in which thousands of its members’ pagers and walkie-talkies exploded. Dozens of the Lebanese Shi‘ite Muslim militants were killed, and thousands maimed or otherwise wounded, including a number of civilians.

Israel did not claim credit. It didn’t need to. Israeli leaders were happy to let the usual blend of fact and plausible fiction help restore the Mossad’s image of invincibility. Hezbollah has been lobbing rockets and shells into northern Israel for 11 months, compelling 60,000 Israelis to leave their homes. For Israelis still traumatized by October 7 and the continuing failure to bring home a hundred hostages missing in Gaza, blasting the guts out of Lebanese enemies allied with Iran felt good.

Intelligence sources confirm that the surprise attack using old-fashioned pagers was the result of years of planning. Mossad personnel posed as foreign brokers and manufacturers of electronic equipment and sold the gear to Hezbollah. (The Hungarian trading firm that reportedly was behind the sale of the pagers was a Mossad-run shell company.) But first, the pagers were in Israel, where the spy agency gingerly inserted undetectably tiny quantities of a powerful explosive—and a chip to receive the detonation signal.

Israel, in effect, sent in a Trojan horse to regain the intimidating image that the Mossad, facing the first anniversary of the Hamas attack, has been desperately trying to recoup. Hezbollah’s leaders—and reportedly Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—have told their fighters to stop using all their electronic devices for fear of further explosive sabotage.

Three days after the shock of the Trojan pagers, the Mossad again showed off its surveillance skills by obtaining precise information that Hezbollah’s chief of staff was meeting with senior subordinates in the basement of an apartment building in southern Beirut. Ibrahim Aqil and 15 of his commanders were killed immediately by four missiles fired by Israel’s air force.

The Hungarian trading firm that reportedly was behind the sale of the pagers was a Mossad-run shell company.

How did Israeli intelligence know about the meeting? Communications intercepts? Spies in that neighborhood? Surveillance by drones or even Israel’s satellites in orbit? The mysteries of methodology serve the Mossad perfectly.

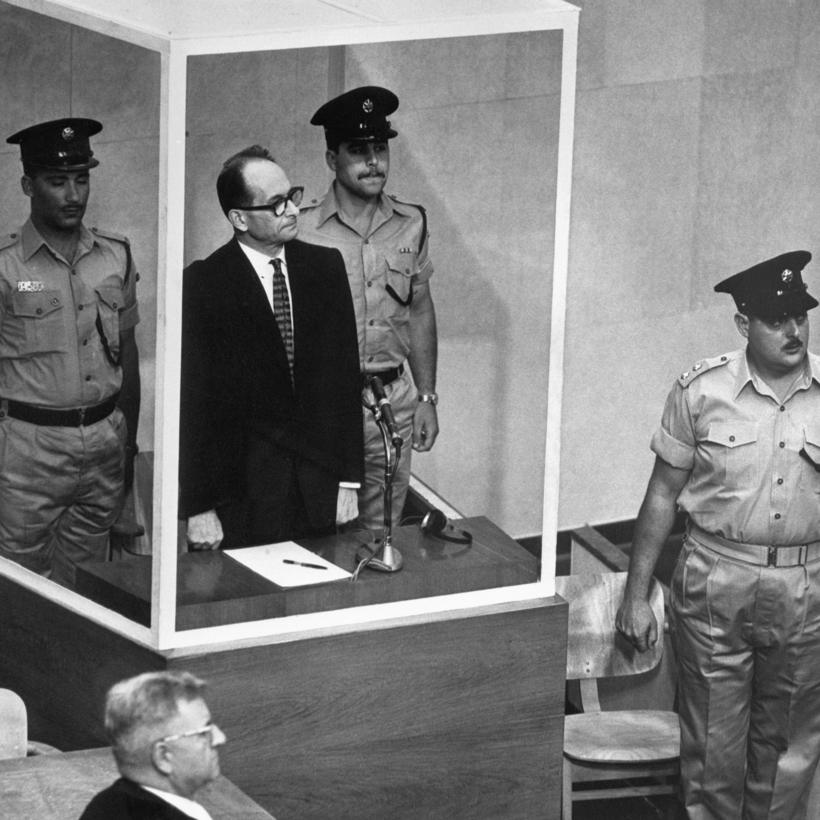

The Mossad was officially formed in 1949, and it earned its first moment of fame in 1960 when agents found Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann and abducted him from Argentina.

Israel’s spies rapidly established their reputation as the finest practitioners of humint—the art of human intelligence—and high-tech spycraft. After 11 Israeli athletes were murdered at the Munich Olympics, in 1972, the Mossad retaliated by assassinating Palestinian terrorists. Details were often foggy in media reports, but Israeli officials were pleased to see that the Mossad was widely considered to be an omnipotent organization, capable of reaching every corner of the world in pursuit of Israel’s enemies.

On occasion, however, there were drug deals or ordinary crimes that newspapers ascribed to the Mossad. In 1984, for instance, Israeli criminals kidnapped a Nigerian politician in London. Umaru Dikko was found, drugged and about to be flown to his home country, with three Israelis in a diplomatic shipping crate at Stansted Airport—a kidnapping method known to be classic Israeli spycraft.

One of the abductors, hired by an Israeli investor at the behest of Nigeria’s president, told us they hoped the impression they were on a Mossad mission would win them a shorter prison sentence. They silently spent more than six years behind bars in Britain.

The agency’s mystique continued to capture the imagination of journalists and authors who concocted preposterous but entertaining stories, usually based on lies and conspiracy theories.

British writer Gordon Thomas’s 1999 book, Gideon’s Spies: The Secret History of the Mossad, claimed the Mossad had audio evidence of President Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky. In this account, the Mossad supposedly threatened to release the recordings because it was unhappy with the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations Clinton was brokering. Israel called the allegation “outrageous.”

For Israelis still traumatized by October 7 and the continuing failure to bring home a hundred hostages missing in Gaza, blasting the guts out of Lebanese enemies allied with Iran felt good.

We had our own experience with Mossad-shaming. In 1997, Yossi was approached by a dubious Israeli journalist, who offered $160,000 if we would write a report that the Mossad colluded with British intelligence to kill Princess Diana in the car crash in August of that year. The man was acting on behalf of Mohamed al-Fayed, the father of Diana’s dead boyfriend. The flamboyant Egyptian-British billionaire who at the time owned Harrods apparently believed in Israel’s guilt and was desperate to find anyone with credentials who would support his theory. We turned down the offer.

This year, the latest victim to fall into the trap of the Mossad mystique was The Jewish Chronicle, a weekly newspaper in London that generally tries to make Israel look good in an era of little but bad news. It published articles by an Israeli calling himself Elon Perry, claiming to have exclusive details of Mossad missions—including Israeli spies in Tehran supposedly dressed in green so they could climb trees undetected to monitor the head of Hamas before he was assassinated in Iran’s capital.

The stories were exciting, and tales of Israeli espionage derring-do tend to sell papers, but the venerable Jewish Chronicle, publishing since 1841, has since concluded the self-described journalist was a fraud and deleted his articles, apologizing to readers.

The Mossad has mixed feelings about conspiratorial allegations and other fantasies. Several operatives, former and current, told us they dislike being portrayed as a kind of Murder, Inc. death squad.

But, said one retired senior spy, “we can’t run around the world chasing fake news and issuing denials. We don’t have time for that.”

He smiled and added, however, “Those kinds of stories, even if they are bad publicity, contribute to our mystique—that for us, the sky is the limit. And besides, whoever it was who said that there is no such thing as bad publicity was right.”

Yossi Melman is a Tel Aviv–based intelligence analyst for Haaretz. Dan Raviv is a Washington, D.C.–based former foreign correspondent for CBS News. Their books include Spies Against Armageddon: Inside Israel’s Secret Wars