In late February 1917—two years after World War I began and just before America entered it—the assistant secretary of the navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, addressed members of the New York Yacht Club (N.Y.Y.C.) in a meeting that likely took place in the club’s Model Room. In what was described in the press as a plea, F.D.R. asked club members to put their yachts at the service of the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. With America’s entrance into the war imminent, the military was woefully short of seagoing vessels.

“I cannot impress upon you too strongly the importance of this help we ask you to render the country,” Roosevelt said near the closing. “You can and will do it, I know.”

By any measure, it was an extraordinary ask. The yachts, many nautical vestiges of the Gilded Age, were some of the most lavish afloat. The 243-foot Harvard, formerly the Eleanor, owned by banker George F. Baker, featured an interior designed by Tiffany & Co., complete with Persian rugs and Barbizon art.

Howard Gould’s 282-foot Niagara featured décor of Renaissance tapestries and a Welte Philharmonic Organ, a huge, complex instrument with 19 ranks of giant pipes, similar in concept to a player piano. Welte luxury instruments were so popular with yacht owners that its advertisements listed the names of ships and owners.

The future president planned to turn these pleasure craft into submarine hunters and convoy escorts. All that luxury of brightwork, well-stocked libraries, and better-stocked wine racks was to be put in harm’s way.

The idea of co-opting the playthings of the rich for war was not entirely without precedent. In Great Britain, stately homes were transformed into military hospitals and training facilities. Twenty years earlier, during the Spanish-American War, F.D.R.’s distant cousin, Teddy, supplemented the understaffed U.S. Army with his Rough Riders—a cavalry regiment—whose members were drawn from Harvard, Yale, and Princeton as well as clubs such as the Knickerbocker, with a few genuine cowboys thrown into the mix.

And yachts did have a tradition of wartime service. Arguably the most renowned of yachts, the 94-foot schooner America, which had been commissioned by a syndicate of N.Y.Y.C. members and was the first winner of what became known as the America’s Cup in 1851, served in the Civil War as both a Confederate blockade runner and, fully armed, in a blockade squadron for the Union.

Roosevelt’s speech could not have been better timed. Germany had resumed unrestricted submarine warfare a few weeks prior, and anti-German sentiment was running high. The sinking of the Lusitania, in 1915, in which more than a thousand perished, was a fresh memory. So, too, was the previous year’s sabotage attack on the Black Tom Island munitions depot, in New Jersey, by German agents. The blast shattered windows in Manhattan and sent debris flying across New York Harbor, damaging the Statue of Liberty.

That German U-boats could reach American shores was amply demonstrated in 1916 when the German submarine U-53 surfaced off Rhode Island, then casually steamed into Newport. In this highly effective piece of propaganda, the crew posed for photos while the captain graciously invited American naval officers aboard. After putting back out to sea, the U-53 proceeded to torpedo multiple cargo vessels in international waters.

Such was U-boat paranoia that the publisher William Randolph Hearst, who maintained unseemly contact with German officials, was reportedly accused of signaling German submarines prowling the Hudson River from his Riverside Drive penthouse. As it turned out, the suspicious colored lights people had seen flashing in his windows were Tiffany glass lamps.

Looking Shipshape

As F.D.R. predicted, response from the N.Y.Y.C. was impressive. Nearly a hundred members pledged suitable yachts for service, while more yachts arrived from other clubs. The names included many of New York’s most prominent families, such as Morgan, Astor, and Vanderbilt. Although some owners sought to make a profit from the navy, asking above the value of the yacht, others leased their ships to the military at the token rate of a dollar a year.

Initially, the request was for yachts at least 100 feet in length with seagoing ability and large cruising range, though those requirements were relaxed in the following months. Very soon, the effort would come to be known as the “Suicide Fleet.”

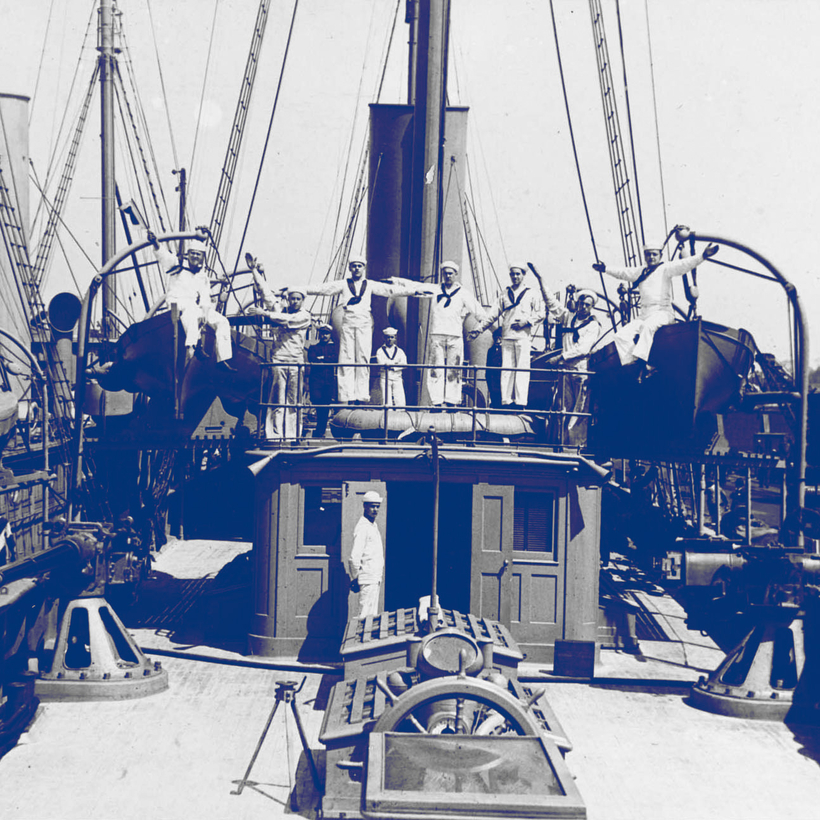

As might be expected, the yachts were not ready for active duty. The retrofitting of Corsair III was typical of the required modifications. Measuring 304 feet in length, she was sturdy but well used, having crossed the Atlantic a half-dozen times during her 18 years.

To prepare her for a war zone, the Corsair’s bowsprit was removed, canvas crow’s nests added to her two masts, and the white pine decks rudely drilled through for mounts for the four three-inch/50-caliber guns placed fore and aft. Tracks for a depth-charge apparatus were laid across the quarterdeck, and a Y-gun, a double-mortar type of depth-charge launcher, was placed at the stern. The teak panels covering the bulwarks were removed, plate-glass windows boarded up, and brasswork painted over. The distinctive black hull was painted gray.

Truckloads of furnishings were removed, and to accommodate a crew of 130, the formal dining room was transformed into a warren of bunks and hammocks, while the cabins and library were outfitted for officers. She emerged from the makeover fully commissioned as Corsair (SP-159) on May 15, 1917.

The effort would come to be known as the “Suicide Fleet.”

America had entered the war on April 6, 1917, and on June 14 the Corsair set sail in a convoy that included the First Expeditionary Force from America to France. The Corsair, along with Oliver Hazard Payne’s Aphrodite (SP-135), a 303-foot combination steam-and-sail yacht, sailed in the first convoy group.

The longtime captain of the Corsair, William Porter, now commissioned as a lieutenant commander, served under Annapolis graduate Commander Theodore Kittinger. Another well-known N.Y.Y.C. yachtsman, Robert E. Tod, a lieutenant, was navigating officer. It was, by most accounts, an egalitarian crew, made up of young men from all walks of life, though the most surprising crew member was a young ensign, Junius Spencer Morgan, grandson of J. P. Morgan, whose family owned the yacht.

Another notable yacht was the U.S.S. Noma (SP-131), belonging to Vincent Astor. Measuring 262 feet, she was originally owned by William Leeds, the “Tin Plate King,” and purchased by Vincent Astor’s father, John Jacob Astor IV, who had perished on the Titanic. As with Morgan, young Astor served as a junior officer on his own craft.

Hazardous escort and sub-hunting duty awaited the yachts in the Atlantic. While acting as a convoy escort, the U.S.S. Alcedo (SP-166) was struck by a torpedo and sank in eight minutes. Owned by Philadelphia newspaper publisher George W. C. Drexel, the Alcedo earned the grim distinction of being the first U.S. warship sank in the war.

While many of the re-purposed yachts performed splendidly as fighting vessels, some fell woefully short. The Margaret (SP-527) was a 176-foot vessel belonging to Isaac Emerson, the “Bromo-Seltzer King” of Baltimore. Essentially a party boat best suited to the calm waters of harbors, she was assessed at $94,000 but sold to the navy for $104,000.

She was not only ill suited for the work ahead but also challenged by the required modifications. Test-firing the fore and aft guns blew out windows, opened seams in the hull, and ripped the armaments from the deck. The coal bunkers were inadequate for long voyages, as were the tanks for fresh water.

The captain, Frank Jack Fletcher, who had received the Medal of Honor for heroism during the United States occupation of Veracruz in 1914, began petitioning for reassignment almost immediately. Even Fletcher’s ill-tempered French bulldog, Poilu, seemed to want off the ship, at one point jumping overboard and requiring rescue. Eventually, Fletcher would get his wish, moving to the U.S. destroyer Benham, then later commanding U.S. naval forces in the North Pacific during W.W. II.

The Margaret was in such poor shape that dockyard workers refused to provision her. And in a final insult, when spotted by a U-boat in the Azores, in the middle of the Atlantic, the submarine’s captain radioed that the Margaret was not worth a torpedo. She finally ended her military career in the Caribbean as a venereal station, where doctors treated sailors for gonorrhea and syphilis. Eventually sold for scrap, she fetched $1,200.

During the ensuing years, naval historians have used the Margaret as an exemplar of the Suicide Fleet. As entertaining as it may be, it is neither entirely accurate nor fair. Many of the ships, though not built for combat, performed well in their new role. And, even more importantly, the same can be said of the ships’ crews.

The history of the Suicide Fleet had its moments of tragedy. When the Alcedo sank, 20 men lost their lives. The U.S.S. Wakiva II (SP-160), which had engaged in multiple battles with U-boats, sank following a collision in dense fog while escorting a convoy off the French coast in May of 1918, with the loss of two men. But there were remarkable acts of heroism too. Ensign Daniel Augustus Joseph Sullivan, serving aboard the Christobel, received the Medal of Honor for securing depth charges that had broken free on deck during an encounter with a U-boat, while Chief Boatswain’s Mate John MacKenzie, serving aboard the Remlik, was also awarded the Medal of Honor for a similar act of heroism while pursuing a U-boat during a storm.

“They were nearly all reservists or recent recruits, the crews of the armed yachts and sub-chasers,” Josephus Daniels, secretary of the navy from 1913 to 1921, wrote. “But they put it over like veterans, and took things as they came. And they had some lively brushes with the ‘subs.’”

Henry R. Schlesinger is a journalist and author who has written about espionage history for more than 20 years. His most recent book is Honey Trapped: Sex, Betrayal and Weaponized Love