October 1973. A car is parked in the lot behind Market Basket, a popular grocery store off busy Ventura Boulevard, in Studio City. As the days pass, patrons and employees begin to smell a noxious odor coming from the car. When police finally arrive, they discover the horrifying cause: in the trunk is the decomposing body of a bound woman. She had been bludgeoned to death.

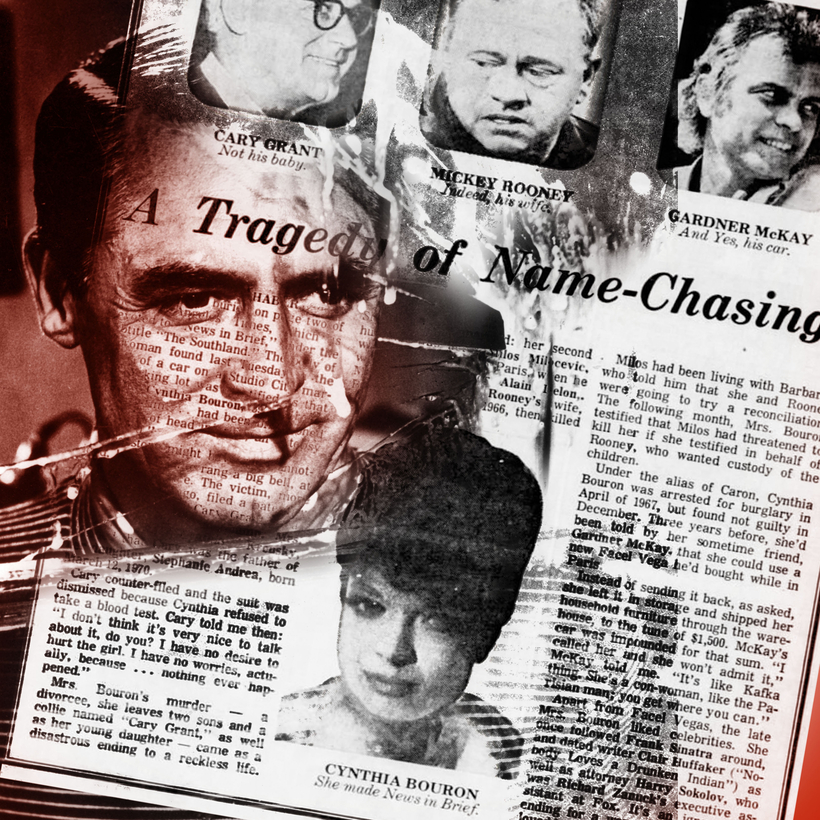

Police identified the victim as the car’s owner, Cynthia Bouron, alias Samantha Lou Bouron, a 39-year-old mother of three who worked as a saleswoman at a local department store. Bouron was not an ordinary mom. In Los Angeles, rumors swirled that she was a call girl. The actor Gardner McKay, a Hollywood star in the 1950s and 1960s, called her a “con-woman.” Three years before her murder, she’d made front-page news for claiming Cary Grant fathered her daughter, Stephanie Strom.

Gossip columnists ran brutal headlines about Bouron’s death. Her murder was a “disastrous ending to a reckless life,” which had been a “tragedy of name chasing,” according to the Los Angeles Times gossip columnist Joyce Haber. No one seemed surprised, or particularly concerned, that this woman with stars in her eyes and her name in the margins had been found stuffed in her own car trunk.

People assumed it was her fault. According to Marc Eliot, who wrote a biography of Grant, North Hollywood police recorded that “several friends of the victim stated she would often pick up men at bars and restaurants.” The police never made an arrest, and the case remains cold.

The Beginning of Bouron

Born on September 24, 1934, Cynthia Louise Krensky grew up in Chicago’s upscale Madison Park. Her father, Albert, worked in investment securities, while her mother, Ida, a stay-at-home mom, indulged her daughter’s fascination with Hollywood. With her regal bearing and high cheekbones, Bouron was “like a beautiful swan,” one friend recalls.

As a teenager, she went to Paris to study and ended up falling in love with a young dentistry student named Robert Bouron. They married in 1956, and two sons, Eric and Marc, quickly followed. But life as a dentist’s wife was not enough. In the early 1960s, Bouron started spending more time in America. Around 1964, she met Miloš Milošević, though no one knows exactly where.

Milošević, born in 1941 in Yugoslavia, was handsome and tough. He roamed the streets of Belgrade with his friend Stevan Marković while, reportedly, working for a gangster named Nikola Milinković. (Marković’s body was found outside Paris in a garbage dump in 1968. His murder was never solved.) In 1962, Milošević, who dreamed of being an actor, met Alain Delon, the French movie star. Delon was in Belgrade to shoot the never-released film Marco Polo. He took a shine to the brash Milošević and Marković, and they soon became his “bodyguards.” Their duties, according to the biography The Life and Times of Mickey Rooney, included “procuring women for an evening’s entertainment.”

When Delon moved to the United States, Milošević followed him, determined to become a star. He adopted the stage name Milos Milos.

From the start, Bouron and Milošević’s relationship was volatile. One night in March 1964, when they were in Miami, Bouron called the police on him. Milošević fled in his Bentley, leading police on what The Miami Herald called a “merry chase” through Golden Beach. When he was finally subdued after resisting arrest, police found a derringer, a revolver, and a tear-gas pen on him.

Despite this, Bouron married Milošević on July 2, 1964. “I was marrying him to save him from deportation to Yugoslavia where he faced a 15-year prison term for army desertion,” Bouron told United Press International. “I told Milos I was marrying him only on the condition that I could have my freedom whenever I wanted.”

The actor Gardner McKay, a Hollywood star in the 1950s and 1960s, called her a “con-woman.”

Soon after, they moved to Los Angeles. Milošević landed a few small roles, and then, in 1966, scored the title role in the campy oddity Incubus, which featured a young William Shatner. Through Delon, Milošević became friends with Mickey Rooney. At 46, Rooney, MGM’s former boy wonder, had become infamous for his philandering, gambling, and drinking. He was on wife No. 5: Barbara Ann, Miss Muscle Beach 1954, with whom he shared four young children.

On July 12, 1965, Milošević was arrested for assaulting Bouron, and she filed for divorce. Meanwhile, Milošević began a torrid affair with Barbara Ann while Rooney was on location in the Philippines shooting Ambush Bay. When Rooney returned and learned of the romance, he filed for divorce.

In January 1966, Rooney, in the hospital after a pill overdose, convinced Barbara Ann to give their marriage another try. On January 30, Milošević went to Barbara Ann’s Brentwood home. While her children were asleep in their bedrooms, he shot her in the jaw and then shot himself in the temple. Their bodies were found the next morning in the bathtub, Milošević lying atop his victim.

Alain Delon took a shine to the brash Miloš Milošević and Stevan Marković, and they soon became his “bodyguards.”

The murder-suicide prompted a worldwide tabloid frenzy. Bouron, still technically married to Milošević, became an object of fascination. Days after the crime, the merry widow was out at Hollywood hot spots. Bouron hit the Daisy, a members-only disco, with TV star Stuart Whitman, dancing next to Natalie Wood, Ryan O’Neal, and Nancy Sinatra. She was spotted at parties hosted by the actor George Hamilton and the artist André Andreoli.

Men absolutely adored Bouron, whom friends describe as charming, gentle, and sensitive. In early 1967, the gossip columnist Louis Sobol reported that Bouron was “finding happiness” with Oscar-winning Swiss star Maximilian Schell, whose proposal she’d allegedly turned down before moving on to his writing partner, the producer and screenwriter Alan Friedman. One night she was seen at Don the Beachcomber, Hollywood’s first tiki bar, with actor Omar Sharif. Another night she was spotted with Twentieth Century Fox producer Harry Sokolov, whom she allegedly dated.

No one seems to know quite what she did. Throughout the 1960s, Bouron was identified in gossip columns as an “attractive personal manager,” a model, a writer, a showgirl, an actress, a producer, and an employee at Twentieth Century Fox. None of these claims have been substantiated, and there are no records of her alleged movie credits. But according to the Desert Sun newspaper, she did a host a call-in show on a local Palm Springs TV station for a time. Graham McCann, who wrote a biography of Grant, describes her as having “a number of very dubious associations.”

This did not stop some of Hollywood’s biggest stars from dating her. Haber says Bouron “followed Frank Sinatra around.” Her friend Marilyn Hinton—a philanthropist and Hollywood socialite—claimed that Bouron dated Sinatra (along with Jerry Lewis), and that he even thought of marrying her but dropped her once he discovered that she lied about being a member of the Bourbon royal family.

After Sinatra, Bouron told Hinton that she had been blacklisted from Hollywood and was broke. Hinton became her mentor and introduced Bouron to her exclusive social set, which included Cary Grant.

Most of Grant’s biographers believe the actor had a brief dalliance with Bouron around 1969. He was reeling from his failed marriage to Dyan Cannon and locked in a nasty custody battle over their daughter, Jennifer, and Bouron was just the kind of woman he liked: beautiful. According to Gary Morecambe and Martin Sterling’s Cary Grant: In Name Only, she spent several nights with Grant in a Las Vegas suite at the Dunes hotel and casino, sharing evenings “featuring candlelight and champagne and sexy evening gowns.”

It was over quickly. But in early 1970, Bouron claimed she was pregnant with Grant’s child, and she made sure the press knew. A mortified Grant, who had spent his long career mostly avoiding scandals, agreed to foot her maternity bill—perhaps because he knew the child could be his, or perhaps in an attempt to keep her quiet.

On March 12, 1970, Bouron gave birth to a baby girl. She named the child Stephanie Andrea Grant, and listed Grant as the father on the birth certificate. “Not since the days of ‘Ben Casey’ had a big-city hospital been bathed in such an aura of intrigue,” Haber wrote in the Los Angeles Times.

To escape the heat, Grant had visited his mother in Bristol and then slipped off to the Bahamas on Howard Hughes’s private plane. But news of the birth could not have come at a worse time for Grant: he was due to accept an honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement at the 1970 Academy Awards, on April 7, after decades of being snubbed by the Academy. Grant told Gregory Peck, the president of the Academy, that he was bowing out of the ceremony so as to not embarrass the institution. He also asked his friend Princess Grace not to present the award, scared that she would be tainted by his scandal. “I feared that if I said I would appear on the Academy stage, I might be subpoenaed right there,” Grant later said. “It would have been the ideal place for [Bouron] to embarrass me and get maximum publicity.”

Howard Hughes and Peck reportedly persuaded Grant to accept the award. He agreed on the condition that they would keep his appearance a surprise so Bouron couldn’t cause trouble.

The April 7 telecast from the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion was a triumph. “I was so nervous that evening when I walked on the stage and the whole audience rose to their feet and clapped, I was close to tears,” Grant later told the London Sunday Express.

But Bouron would not go away. In May, she filed a paternity suit, asking for “reasonable support.” Days later, Grant cross-filed in Santa Monica, asking the court to stop Bouron from claiming he was Stephanie’s father. According to Hinton, Grant had hired a private eye to break into Bouron’s apartment and peek at baby Stephanie. He was assured the child looked nothing like him. According to a police report, the child had Black parentage. (Strom identifies as bi-racial.)

The court ordered Grant, Stephanie, and Bouron to submit to a blood test. While Grant complied, Bouron took off for London. She stayed there for months, missing three mandated tests. Even so, she continued to press her case to reporters. She also retained the services of Paul Caruso, the lawyer representing Patricia Parker, who filed a failed paternity suit against Elvis Presley that same year. In November, Bouron sent a pair of Stephanie’s booties to Grant, who was staying at the Dorchester in London, with a note that read, “You wouldn’t want to be in my shoes.” A year later, she was still claiming she would file a new child-support suit in New York if only she could come up with the funds.

After the uproar over Grant, Bouron spent some time in Palm Springs, with The Desert Sun reporting that she was “known for association with the entertainment element and nightlife world of the area.” In March 1972, she popped up in the gossip columns for the last time, for going to a party hosted by Jolie Gabor, which was attended by her daughter Eva, Rock Hudson, and Prince Umberto de Poliolo.

By March 1973, she was back in Los Angeles. In her mysterious final days, Bouron may have known she was in danger. According to Strom, who was then three, her mother had sent her to stay with a family friend a couple of weeks before the murder.

“You wouldn’t want to be in my shoes.”

On October 20, Bouron’s teenage sons reported her missing after not having seen her for three days. Ten days later: the awful discovery. According to Strom, Bouron was bound in the incaprettamento fashion of the Italian Mafia, which causes strangulation. “It’s the final diss, like showing disrespect,” she says. “It’s like warning everyone else who might think of crossing them, they’re making an example out of this person, even after they’re gone. It’s all about sending that cold message: Betray us and this is what you get.”

In the days after Bouron’s murder, police interviewed unnamed suspects. Then: silence. Bouron’s mother allegedly hired her own private investigator, traveling to Los Angeles in an attempt to find her daughter’s killer, but her efforts were in vain. There was speculation that she was killed by a Milošević associate or an abusive boyfriend. Today, her murder is still unsolved.

The L.A.P.D. would not comment on the crime, stating only that “the case is currently marked unsolved.” Years ago, Strom had friends in public service look into the case, and attempted to piece together her fractured memories for any clues, but she has yet to find any leads.

After her mother’s death, Strom was adopted by a family in San Diego and arrived at her new home in beautiful clothes supplied by her grandmother. Throughout her childhood, her grandmother would visit her, telling her stories of a mother she was not sure she remembered. Storm did not learn what happened until she was a teenager. “I became what some would say rebellious as a teenager, and my [adoptive] mom said, ‘You’re going to end up tied up and dead in the trunk of your own car, just like your mother, like Cynthia Bouron,’” she says. “That was the day I found out what happened to my mother and why I was adopted.”

Strom repeated many of her mother’s patterns, becoming mixed up in the seedy side of Los Angeles’s entertainment scene and abusive relationships. “It’s like this generational curse,” she says. A decade ago, she left that painful life behind. “I wanted my nieces to have a triumphant story about their aunt instead of a tragic one like I had about my mom.”

“If you’re a good person stuck in something bad, I’m sure you’d look for a way out,” says Strom. “We need to understand that Cynthia Bouron never found that chance.”

Strom is still looking to locate her brothers, Eric and Marc, who disappeared after Bouron’s murder. Since she was so young at the time of the murder, she does not remember them. One family friend believes they were sent by Bouron’s family to boarding school in the Midwest after the death.

While she tries to live in the moment, she would like for the case to be re-examined. “I hate that it was never solved,” Strom says. “I imagine somebody’s still out there.”

Hadley Meares is a Los Angeles–based writer