“This country’s not coming apart at the seams, for heaven’s sakes,” the president said. This was 1992, as George Herbert Walker Bush—successor to the landslide popularity of Ronald Reagan, steward of the United States’ triumph over the Soviet Union in the Cold War, victor in a real shooting war in Kuwait—tried to understand why he was up on the debate stage with not one but two people who were running on the message that the public was sick of how things were. Why couldn’t the incumbent president show them that America wasn’t really in crisis?

There was plenty to be upset about at the dawn of the 90s: a deep recession and “jobless recovery,” rampant crime, the gutting of once-reliable employment sectors, official malfeasance, rioting. But as John Ganz writes in When the Clock Broke: Con Men, Conspiracists, and How America Cracked Up in the Early 1990s, the mood wasn’t a matter of rational cause and effect. “People wanted to be pissed off, but the specifics were too irritating and difficult,” Ganz writes. “Reality had to be left behind.”

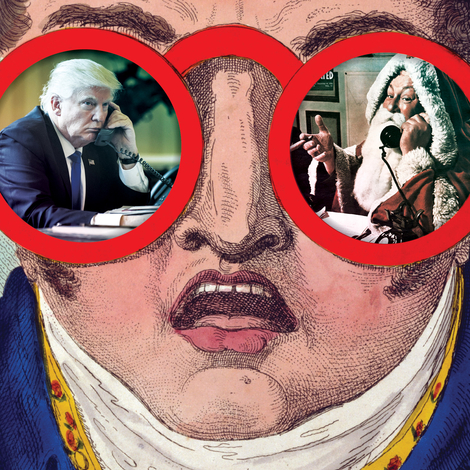

The resemblance to the mood of an era even nearer to our own—the mood of “American Carnage” and “Stop the Steal” and the opinion-poll malaise surrounding Bidenomics—is meant to haunt the reader, and it does. In When the Clock Broke, Ganz, a history-minded essayist and successful newsletter pamphleteer, systematically dismantles the comforting notion that the current civic emergency is some unprecedented break with history. A quarter-century before the age of Donald Trump, Ganz writes, much of the country was already simmering with a “politics of national despair,” a fluid mix of reactionary resentments looking for something or someone to crystallize them.

“People wanted to be pissed off, but the specifics were too irritating and difficult.... Reality had to be left behind.”

It would be simple enough to hammer away at an argument that history is repeating itself, with high-minded warnings about “corrosive cynicism” in politics and low-minded ones about an “illegal invasion” at the southern border, “growing encampments of homeless migrants” in Southern California, and a conspiracy-promoting third-party presidential candidate running on shamelessly vague promises of “action.”

But after spelling out the premise of the book—that today’s Republican Party is controlled by “figures and ideas that once would have been considered fringe”—Ganz lets the happenings of history speak on their own terms, re-invested with the energy and ridiculousness of current events, trusting the reader to hear the alarming echoes and harmonies.

Thus he describes a focus group of “white, blue-collar swing voters” convened by the opponents of David Duke, the Klansman and neo-Nazi turned Louisiana state legislator, as he mounted an alarmingly energetic campaign for governor in 1991: asked about “a hypothetical candidate who had dodged the draft, avoided taxes, had plastic surgery, and never held a job,” the voters were disgusted—until they were told that the candidate was Duke, at which point they “grew testy and defended him.” According to Ganz, one woman said, “Only dumb people pay taxes.”

Ganz does not bother pointing out that this is also what Donald Trump would say, much later, about his own tax dodging. The story stays right there in the early 90s, as the moral and mental habits of those benighted Louisiana voters—and the politics that go with them—work their way outward and upward from Duke through the national media to the 1992 presidential campaign of Pat Buchanan and onto the stage of the Republican National Convention. Ganz shows those attitudes seeping at the same time into the other campaigns, too: the independent celebrity-billionaire one of H. Ross Perot and the eventually victorious, ostensibly liberal one of Bill Clinton.

How did a racist local weirdo such as Duke set the tone for national politics? One answer is that the racism was nihilistically entertaining. Ganz describes ABC’s Ted Koppel solemnly warning the viewers of Nightline that Duke was a natural exploiter of the TV medium. “Then Nightline proceeded to give him thirty minutes of free airtime,” Ganz writes. When Pat Buchanan—who’d urged Republicans to “expropriate” Duke’s “portfolio of winning issues”—gets in trouble for his own record of flagrant anti-Semitism, he is defended by Michael Kinsley of The New Republic, “Pat’s opposite number on CNN’s Crossfire.”

But Duke and Buchanan also caught on because the press, and no small share of the Democratic establishment, sympathized with their message. When Buchanan gives his raging, gay- and race-baiting “culture war” address at the R.N.C., ABC’s David Brinkley judges it an “astoundingly good speech.” Ganz finds the liberal academics Thomas and Mary Edsall complaining about “prohibitions against discussion of family structure among the black poor” and Representative Barney Frank lamenting in The New York Times that liberals couldn’t discuss the criminality of young Black men—en route to Bill Clinton sandbagging Jesse Jackson at the Rainbow Coalition’s leadership conference, after telling the audience not to “be prisoners of the past or the politically correct” with his attack on Sister Souljah. “In a headline on her syndicated column,” Ganz writes, “Mary McGrory, white, declared, BILL CLINTON IS STARTING TO LOOK LIKE A SAVVY POLITICIAN.”

How did a racist local weirdo such as David Duke, the Klansman and neo-Nazi turned Louisiana state legislator, set the tone for national politics?

Behind the emotional and opportunistic politics, Ganz tracks the right-wing thinkers and polemicists—the paleoconservative Samuel Francis of the Heritage Foundation and Washington Times, the paleolibertarian Murray Rothbard of the Cato Institute, Buchanan himself—trying to polish it into a reactionary populist movement. Like the morally flexible pro-Duke focus group, Francis and Rothbard set aside their disagreements on minor points such as “the existence of the nation state” to get behind Buchanan, as Rothbard put it in a speech, on behalf of “the status anxious, paranoid, deeply resentful, radical Right.”

“With Pat Buchanan as our leader,” Rothbard declared, “we shall break the clock of social democracy.... We shall repeal the twentieth century.” In response, Ganz quotes an attendee as saying, “The crowd leapt to their feet, cheering wildly, ready to storm the capital.”

Again, the resonance is left to work on its own. Ganz’s 1990s sound like today because they sound like America. This creates the space for more intriguing thoughts to develop; a chapter on Rush Limbaugh and the masculine mass-media aggression of shock-talk radio, amplified by corporate consolidation, turns to the matter of large-scale male loneliness.

Ganz describes the territory of Limbaugh, Don Imus, and Howard Stern as “a far-flung empire peopled with autonomous, equal citizens, each with a sense of his own right to be heard and redressed.” Then he picks out one voice from that atomized collective: “Donald Trump became a regular caller to the Stern show around the time of his highly publicized divorce from Ivana.”

For all the grave implications of his subject, Ganz tells his story with sly timing and an appreciation of the absurd—essential for describing the spectacle of the off-and-on Perot campaign, in which a priggish corporate martinet (who as a young navy officer once wrote to Senator Lyndon Johnson to complain about hearing his men’s “drunken tales of moral emptiness” and “passing out penicillin pills”) contrived to make himself an avatar of the American political id.

Here was a government reformer who got rich charging four times the accepted profit on government contracts, a “champion of thrift and rugged pioneer virtues” who “was dependent on the welfare state.” His volunteers, Ganz reports, built an “eight-foot plaster of paris bust” of him as a monument, and then, when he (temporarily) dropped out of the race, “placed a noose around its neck, and forklifted it into a dumpster.”

“We shall break the clock of social democracy.... We shall repeal the twentieth century.”

Dignity is hard to come by, and even harder to square with the historical record. The penultimate chapter zooms in on New York to tell the story of Rudolph Giuliani, and how a publicly uptight, Mob-hunting prosecutor—who “wasn’t comfortable with race-baiting” in his losing 1989 mayoral campaign against David Dinkins—found himself three years later presiding over a riot as 10,000 N.Y.P.D. officers, furious at the prospect of increased civilian oversight, besieged City Hall, shouted racist slogans, and drunkenly beat people in the streets in broad daylight.

Giuliani, once disparaged as a “Lisping Sheriff of Nottingham” and “fair-weather Italian” in a city where John Gotti was a folk hero, discovered in the bigoted and lawless cops the energy that had been missing from his political career.

Becoming the candidate of the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, Ganz writes drily, “required him to temper his old zeal as untouchable anti-graft fighter a bit.” Here was how the would-be mayor could gain the kind of public stature enjoyed by a racketeer and murderer. “When New York turned its lonely eyes to John Gotti,” Ganz writes, “it was longing for another kind of authority than the type Giuliani had represented up to that point.”

Rothbard and Francis, the intellectual authors of the would-be movement to abolish the 20th century, both saw The Godfather as a model of society, just as the tabloids saw Gotti as a hero. In place of “law, universalism, meritocracy, rationality, bureaucracy, good government, reform, blind justice, and all that bullshit,” Ganz writes, the city wanted “protection, a godfather, a boss.... Gotti was not really a figure of revolt and anarchy at all, he was a symbol of order, the old order that many longed for still, an order more real and deeper than the law, upheld by brute power.”

“Giuliani understood,” Ganz writes, “that the voice of real authority was obscene.” A little more than two decades later, after his own career had peaked and faded, the now former mayor would get the chance to hear just how loud that voice could be.

Tom Scocca is the former politics editor at Slate and the editor at Popula