On Boris Johnson’s desk in Number 10 stands a bust of the Athenian leader Pericles – his “hero” and “inspiration” for forty years. Tom Bower, who has made his name trying to destroy the reputation of famous figures (from Richard Branson to Prince Charles), chooses in this new biography of Boris Johnson to provoke through rehabilitation – to invite comparisons with figures such as Pericles by praising Johnson’s personality, talents, political successes and character.

Bower tells us that Johnson can be warm-hearted, kind and genuinely polite, that he is not gossipy or malicious, and that he is generous, believes the best of people and lacks pettiness or envy. He reminds us of “Johnson’s magic combination of intelligence, wit, cunning and exhibitionism” which – allied to a formidable memory, and a facility with words – has made him one of the most highly paid writers and speakers of his generation. He minimizes Johnson’s misdemeanors – not by omitting them, but rather by listing so many that they lose their power to shock. Thus, the first time he describes Johnson cheating on his wife, and lying, it is disturbing; but when Bower describes the fourth affair and Johnson’s claim that “It is complete balderdash. It is an inverted pyramid of piffle. It is all completely untrue and ludicrous conjecture …”, it is bathetic.

Things that would seem humiliating lapses in others (such as Johnson’s prevarications to avoid leaving his official residence when he resigned as foreign secretary) are made to seem predictable and “authentic”. The countless times when he lets people down subliminally readjust our expectations, so that on the rare occasions when Johnson does what is required for the job (gets up early to read his briefings as mayor of London, for example) it appears a sign of heroic diligence. And when Johnson behaves particularly badly, Bower is able to excuse it as a product of an unhappy childhood, with a mother who had a breakdown and a stingy father who (according to Johnson’s mother) kept them in cold houses, cheated on her, and hit her in front of their young son.

The first time the author describes Johnson cheating on his wife, and lying, it is disturbing; but when he describes the fourth affair, it is bathetic.

There are other compliments that could be paid to Johnson. Bower is not strong on his sense of humor, or flashes of learning. He passes quickly, for example, over the impressive lecture Johnson gave on the Latin poet Horace in 2004. There are some characteristic Johnson touches in that speech (he emphasizes Horace’s hypocrisies, cowardice and compromises over the more dignified and stoical elements in the Odes; and reduces the poetry to the question of whether journalists are more important than politicians). But it is impossible to deny the ease and enjoyment with which Johnson cites Latin verse. And few other public figures would have observed that “there is a final sense in which Horace is not just a ward and protégé of Mercury but also carries out the ultimate function of that divinity”.

It is above all, however, as a successful politician that Bower invites us to admire Johnson. He bet on the side of Leave in the Brexit referendum when the polls were against it. He persevered after his first failed leadership campaign. He resigned as foreign secretary, although resignation is generally fatal to a political career. And on the basis of all this became prime minister, just as he twice before became a Conservative mayor in a Labour city. Then – having defied parliament and the Supreme Court, brought in an unpopular and provocative Chief Adviser, fired some of the most senior and well-known members of his own party (and also others including me), and called an election when the polls were unpromising – he won an astonishing majority. He appears able to sense and grab the tail of the galloping horse of history, when everyone else is still wondering where it might be stabled.

Even this underestimates his achievement. Johnson is not simply an opportunist, exploiting impersonal historical forces; he has often created these events – whistling the horse of history to himself, and whipping it on its way. In 2019, he faced the same Labour leader and the same Brexit conundrum that led Theresa May to lose her majority two years earlier, and with a highly personal and idiosyncratic campaign won an eighty-seat majority. And his disproportionate impact on that election, which was not apparent in the early polls, also suggests that he did not simply benefit from the vote for Brexit, but made it happen. Bower concludes, therefore, that those of us who criticize him – as I am about to do – are narrow-minded, prudish, inadequate or envious.

Shades of Green

Perhaps it is envy. Johnson is after all the most accomplished liar in public life – perhaps the best liar ever to serve as prime minister. Some of this may have been a natural talent – but a lifetime of practice and study has allowed him to uncover new possibilities which go well beyond all the classifications of dishonesty attempted by classical theorists like St Augustine. He has mastered the use of error, omission, exaggeration, diminution, equivocation and flat denial. He has perfected casuistry, circumlocution, false equivalence and false analogy. He is equally adept at the ironic jest, the fib and the grand lie; the weasel word and the half-truth; the hyperbolic lie, the obvious lie, and the bullshit lie – which may inadvertently be true. And because he has been so famous for this skill for so long, he can use his reputation to ascend to new levels of playful paradox. Thus he could say to me “Rory, don’t believe anything I am about to say, but I would like you to be in my cabinet” – and still have me laugh in admiration.

But what makes him unusual in a politician is that his dishonesty has no clear political intent. Lyndon Johnson’s corrupt and dishonest methods were ultimately directed towards Civil Rights Reform; Alberto Fujimori’s lies enabled a complete restructuring of the Peruvian economy. Machiavelli argues on the basis of such examples that dissimulation may be necessary for effective political action. But Johnson proves that it is not sufficient.

Johnson appears able to sense and grab the tail of the galloping horse of history, when everyone else is still wondering where it might be stabled.

I saw almost daily, when he was foreign secretary and I was one of his Ministers of State, how reluctant he was to push through even those policies that he professed to endorse. He demanded, for example, to know why we were not doing more for “charismatic megafauna”, but when I came back with an $11.8 million program to work with the German development agency on elephant protection in Zambia, he simply laughed and said “Germans? Nein. Nein …”.

He said, “Rory: Libya. Libya is a bite-sized British problem. Let’s sort out Libya”, but when I proposed a budget, and some ideas on how we might work with the UN and the Italians in the West of Libya, he switched off immediately. “Cultural heritage”, he told me, “is literally the only thing I care about in the world”, but again I could not get him to support a fund on cultural heritage. Even when he did rouse himself to action, as mayor, the results often seemed not what he intended – having campaigned against skyscrapers, for example, and in favor of emulating the architecture of Periclean Athens, he left a legacy of some of the most ill-considered, inhuman towers in London (Nine Elms in Vauxhall being a dramatic example).

What makes Johnson unusual in a politician is that his dishonesty has no clear political intent.

Why? Was it that implementing his policies would have involved challenging another point of view and he did not want to make anyone unhappy? Did he lose interest because I had reduced “charismatic megafauna” to actual elephants, or “the bite-sized British problem” to a slow multilateral effort? Was it allergy to detail, which meant that, two-and-a-half years after the Brexit vote, he still struggled to understand the Customs Union, was blind to the issue of Irish borders, and kept saying that we could have a transition period without an agreement? Why did he fail to grasp the implications of Coronavirus in February?

Johnson’s explanation for all these things is that he suffers from the classical vice of akrasia. He knows what the right thing to do is but acts against his better judgement through lack of self-control. He is, in Aristotle’s words, like “a city that votes for all the right decrees and has good laws but does not apply them”. But Johnson’s lack of so many of the other virtues listed by Aristotle – temperance, generosity (he is notoriously reluctant to reach for his wallet), realistic ambition, truthfulness or modesty – is startling. It is hard to accept that in every case he agrees on what is good, and intends it, but somehow frustrates himself from achieving it – rather than in fact having quite different beliefs, priorities and intentions.

Through the Boris Glass

This lack of moral conviction is not a secret. Rather than fooling everyone, he has in a sense never fooled anyone. Siblings, parents, teachers, bosses, subordinates, colleagues and friends have always seen through him. His housemaster at Eton wrote about the teenage Johnson’s “gross failure of responsibility” and his sense that he was “an exception, one who should be free of the network of obligation which binds everyone else”. His first Editor at The Times fired him thirty years ago for lying. His next editor at the Daily Telegraph called him “a morally bankrupt cavorting charlatan, rooted in a contempt for the truth”.

And the public are fully aware of this. Nevertheless, millions voted for him to be prime minister – some with great enthusiasm. Is this because many assume that no politician could actually be diligent, competent or sincerely dedicated to public service? And that if someone – a Theresa May or Keir Starmer, for example – claims to be one of these things, they must be deceiving us? Johnson believes so, and this frames his political approach. “Self-deprecation is a very cunning device”, he explains, “all about understanding that basically people regard politicians as a bunch of shysters.”

His speeches, therefore, are written not to dampen but to titillate the public’s sense of scandal, and embarrassment. Take his most familiar speech, which begins with an attack on regulations, and Health and Safety, but continues:

“Which is why my political hero is the mayor from JAWS.”

Laughter.

“Yes. Because he KEPT THE BEACHES OPEN.”

“Now, I accept,” he goes on in an uncertain tone, “that as a result some small children were eaten by a shark …”

The audience follows Johnson down the path of their shared hatred of Health and Safety, only to discover with delight that he has, apparently inadvertently, endorsed the eating of children. Johnson never poses as our better – rather he goes out of his way to exaggerate his incompetence. Take again his central speech during the election campaign, when he stood in front of a row of police and asked:

“You know the police caution…?”

Long pause while he apparently tries to remember.

“‘You do not have to say anything …’ Is that right? ‘But anything you say …’” Pause “No … ‘but if you fail to mention something which you later rely on’ … hang on let’s get this right …’” Pause. “Anyway you get the gist.”

His housemaster at Eton wrote about the teenage Johnson’s “gross failure of responsibility.” His first Editor at The Times fired him thirty years ago for lying.

Instead of the politician who tries to impress us with knowledge, Johnson flatters us by allowing us to feel we always know more than him.

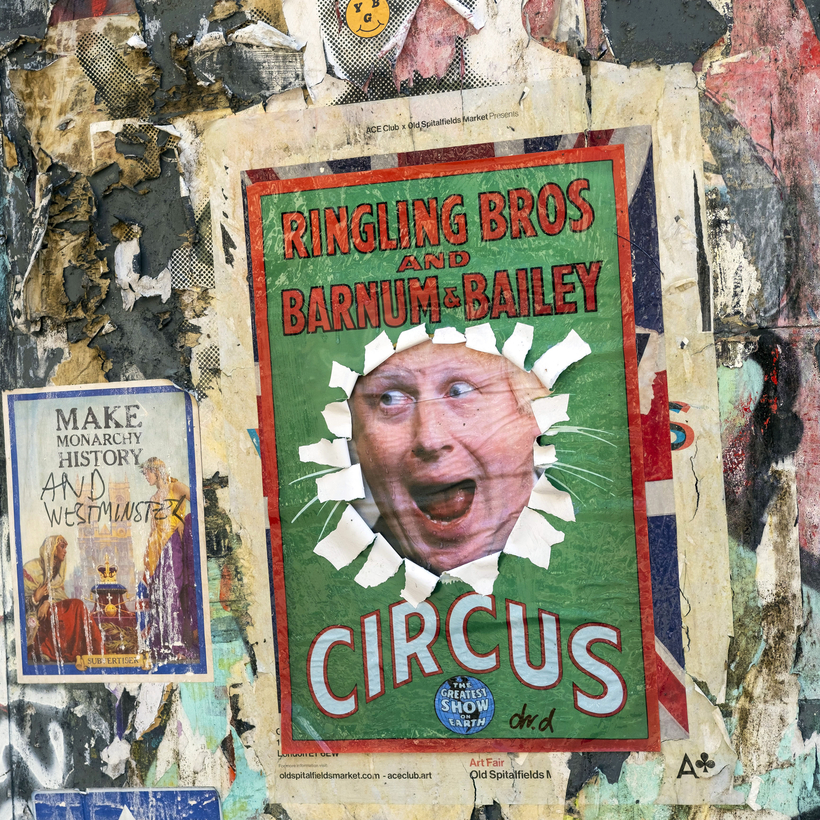

Why is this so particularly appealing? Is it that voters want him to confirm their distrust of all elites and high-minded stories? Or to validate some conviction that there can be no true moral or political purpose, no sincere vision of self or country? Or does his disregard for red lights, the edges of racism and homophobia in his humor, the flamboyant ricketiness of his life and finances, his refusal (until very recently) to eat well, drink sensibly, watch his weight, and still less act professionally, tuck in his shirt or brush his hair – while still becoming prime minister – make us feel better about ourselves? Is he a carnival lord of misrule allowing us to rebel against the oppressive expectations of our age, or a hand-grenade to be thrown at the establishment?

Whichever it is, Bower is wrong to suggest that Johnson is seeking to emulate the heroes of ancient Greece. Johnson states grandly that “every skill and every pursuit and every practical effort or undertaking seems to aim at some good, says old Aristotle, my all-time hero. And that goal is happiness”. But Johnson’s notion of happiness seems a much thinner thing than Aristotle’s life of honor and virtue. It is more akin to pleasure, and insufficient to provide a rich, flexible or satisfying purpose to his political life. Again, Johnson often compares himself to Pericles on the grounds that they both enjoy good speeches, democratic engagement, big infrastructure and fame. But Pericles built the Parthenon, not the Emirates Cable Car. And if, like Johnson, he had made and lost a $1,300 bet, he would have wanted to pay it, and be known to have paid it (rather than sending Max Hastings an envelope with a note saying “cheque enclosed” with no check).

Johnson often compares himself to Pericles on the grounds that they both enjoy good speeches, democratic engagement, big infrastructure and fame. But Pericles built the Parthenon, not the Emirates Cable Car.

These differences are not trivial. It is not simply that Pericles had more self-control, allowing him to act more prudently. It is that Pericles’ understanding of which drama and architecture to sponsor, when not to attend a private party, when to speak and when to be silent, and why fame was worthwhile, was rooted in a notion of personal honor, and the honor of the state. Gladstone and Churchill, also – in their very different context – had a sense of personal and national honor (and it can be traced from Churchill’s grand historiographical writing to his micromanagement of the detailed designs of a bomb shelter). Johnson does not. And if Johnson is not a virtuous Greek, still less is he a stoical Roman. Johnson’s delight in bluff, and in what the Romans would have called levitas and impudentia, is the antithesis of the Roman ideal – and a direct rejection of the Roman statesman’s dignitas and gravitas.

Instead, Johnson’s way with words, his irrepressibility, his recklessness (and caution with money), his lofty references and brutal politics, and his tricks echo the less familiar moral universe of Norse literature. Like Egil’s saga, his life shocks and impresses us with the resilience, shamelessness and cunning (disguised as simplicity) that allows him to continually embarrass and defeat every conceivable authority and constraint – teacher and colleague, boss and husband – seizing power through trickery.

Johnson may have a bust of Pericles on his desk. But he is not, as he pretends, a man suffering from akrasia – someone who struggles, with shame, to live up to the ideals of a complex classical civilization. Rather, he is an amoral figure operating in a much bleaker and coarser culture. And it is in his interest – and that of other similar politicians around the world – to make that culture ever coarser. But unless we begin to repair our political institutions and nurture a society that places more emphasis on personal and political virtue, we will have more to fear than Boris Johnson.

Rory Stewart is a British diplomat, politician, and writer. He is the author of The Places in Between